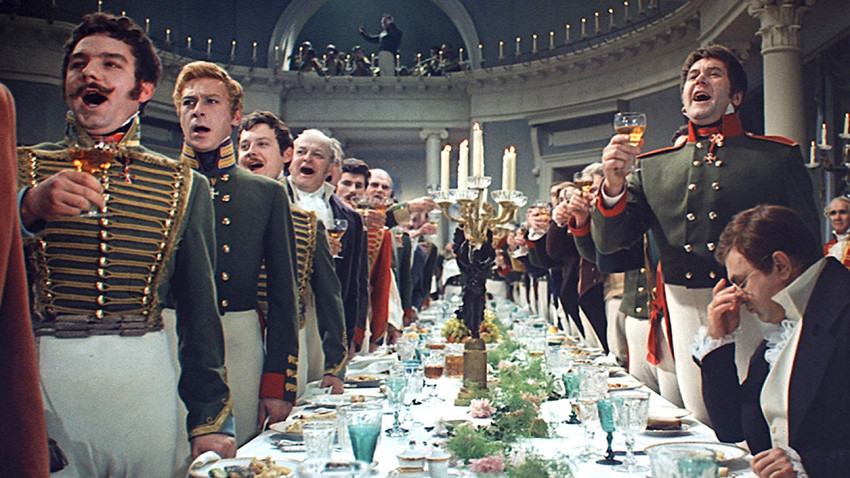

"War and Peace"

Sergei Bondarchuk, Vasily Solovyov/Mosfilm, 1967

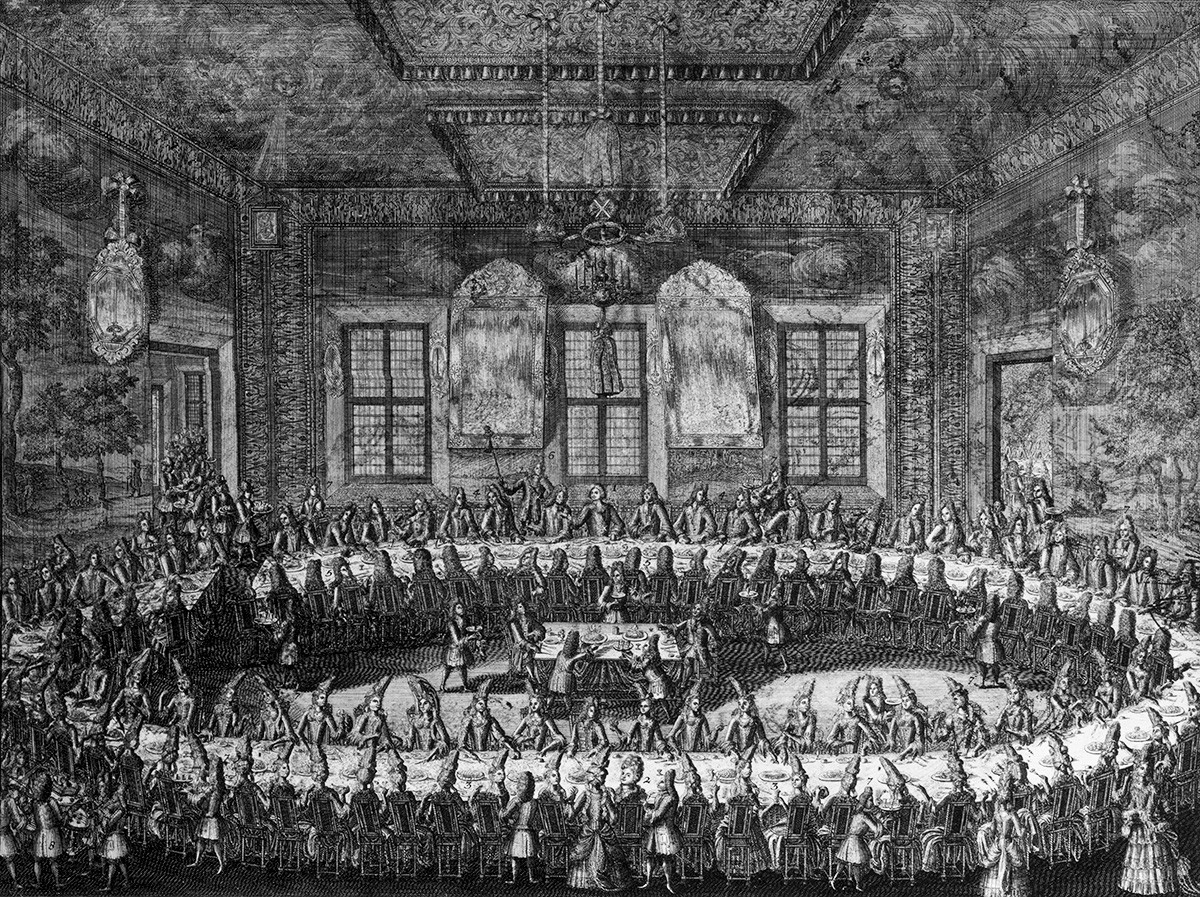

Wedding of Peter I and Catherine I on February 13, 1712.

Alexei Zubov/Global Look PressThe vogue for foreign chefs in Russia dates back to the early 18th century and the wanderings of Tsar Peter the Great around Western Europe, from where he brought back many foreign novelties. When he returned, wealthy people began to hire foreign chefs, including from France. The trend developed further under his daughter, Empress Elizabeth, when the nobles adopted the French language, and Russian aristocratic cuisine began to imitate Versailles. All dishes were served together at once, and the tables were decorated with outlandish feathers, miniature fountains, and bouquets of fresh and artificial flowers. For dessert, soaked apples, salted watermelons and lemons, and sugared melons were supplemented with curiosities from France and Italy — sweets and marmalades.

The reign of Catherine the Great, who corresponded extensively with Voltaire and other French philosophers, coincided with the French Revolution of 1789, when a section of the French nobility emigrated to Russia with their servants. Some prospered, others not, but many happened to find work in the gastronomic field. The newly arrived French found themselves in demand. Through the influence of French chefs, French culinary methods gradually began to take root in Russia. This was reflected in the combination of ingredients, the precise formulation of dishes, and the use of minced products. Before that, for example, fish and meat for pies were cut into layers, not ground up. Also adopted were French dishes and their names: cutlets, mousses, omelets, salads (these French-borrowed words sound almost identical in Russian). Moreover, Russian and foreign dishes began to alternate within a single Russian meal.

"The Hussar Ballad" is dedicated to the Battle of Borodino

Eldar Ryazanov/Mosfilm, 1962During the 1812 war between Russia and France, Russian nobles were in a quandary. For patriotic reasons, they felt obliged to speak less in French (the Russian nobility was highly Gallicized) and more in Russian, which did not come easy to many (readers of War & Peace may recall how Prince Kuragin was unable to tell a joke in Russian). Worse perhaps, they also felt it their duty to forsake French food. But at least this did not significantly affect their calorie intake: meat, pickles, and kvass were still readily available. Ordinary people, meanwhile, especially in the provinces, were still unaware of the delights of French cuisine.

Officers and soldiers received all necessities from the Russian War Ministry, but nothing more. During campaigns and on guard, soldiers could go without food for a whole day, so they took bread with them as an anti-hunger precaution. The standard daily diet included schi (cabbage soup) — with small fish and vegetable oil on fasting days, and salo (lard) or beef at other times. Flour and cereals (most often buckwheat) were supplied by the state. The flour went into making bread (each soldier received a daily ration of 1.2 kg) and the cereals into porridge. As the army moved around, soldiers bought vegetables, dairy products, and eggs from local peasants. In sickbays, soldiers and officers were fed oatmeal or buckwheat porridge with butter, white bread, broth, lightly-boiled egg, and kissel (a thin jelly drink). They also cooked poultry and fish, and made schi from nettles.

During the war, Russian soldiers spied an unusual recipe from the French — cucumbers with honey. Since the fresh cucumber season was nearing the end, salted ones became mainstream. Belief in the medicinal properties of pickles (for digestion and gout) did not end with the war and live on to this day.

Back then, the humble potato had yet to strike root (so to speak) in society, especially among the peasantry. But the shortage of food forced people to reassess their relationship with this strange product. It was noted how the French commandeered potatoes from the local population, and baked them over an open fire. Then there was mashed potato… In Russia, however, it is still often pushed through a ricer, rather than grated in the French manner, is much simpler (made with milk and butter), and totally ubiquitous.

Sharlotka with blackcurrant kissel baked by a talented chef Evgeny Mikhailov, Drinks & Dinners

Maria AfoninaFinally, in March 1814, Russian troops led by Alexander I entered Paris. French chef Marie-Antoine Carême prepared a “Parisian charlotte” for dessert, changing the epithet to “Russian.” To flatter the tsar, Alexander was told that it was named after Charlotte of Prussia, the wife of his brother, the future Nicholas I. His royal highness was so impressed by the dessert that he invited Carême to St Petersburg, where he worked for several months. “Russian charlotte” (sharlotka) has since worked its way into many cuisines of the world, not to mention Russia itself.

Read more: “Lazy” Napoleon: This delicious dessert will be the delight of your party

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox