Russians are huge tea lovers, able to have up to 10 cups a day without raising an eyebrow. And the variety of teas on offer is staggering, even in some of the smallest tea stores: there’s tea in leaves, in bags, black, green, herbal - all of them further subdivided into dozens of further varieties. But there’s one thing no Russian tea store has ever sold: the famous “Russian tea” that you see on Western shelves.

Russia sells English Earl Grey; Europe, meanwhile, sells something called ‘Russian Earl Grey’, produced by major brands such as Lipton, Twinings and others. So what’s the big difference? It’s a common belief that flavored teas don’t go well with lemon, as it kills the added aromas the original tea has been infused with.

Earl Grey gets its flavor from the oil of a particularly fragrant species of orange-like citrus fruit, called ‘bergamot orange’ - bergamot also being the name of the oil. Adding milk or lemon risks ruining the delicate flavor. But Russians simply don’t care, and many throw in a slice of lemon anyway. Little by little, as others started to mimic the trend, people discovered that the mixture of flavors also had a solid fan base. And that’s the story of how ‘Russian Earl Grey’ arrived on the market.

Russians are, on the whole, massive fans of having tea with lemon; while other cultures may opt for lemon zest or a splash of lemon juice, it’s Russia where the custom of throwing in a whole slice originated.

Lemons appeared in the Russian Empire thanks to Peter I, who brought them over from Europe in the early 18th century. At first, the fruit was grown in Oranienbaum (a name derived from Dutch and German words for “orange tree”), outside St. Petersburg, and in the orangeries of aristocrats. Afterwards, the trees started popping up in the regions, and in this way, growing a small lemon tree right on one’s window became common practice.

The harvest from those wasn’t too big - only about 10-15 lemons annually, but it was enough for one family. But the story of how it became a staple of tea-drinking is a little funnier, and has everything to do with… bad roads.

People found out that a slice of lemon was really good for car sickness - as we know the condition today. And that’s how they ended up in our tea.

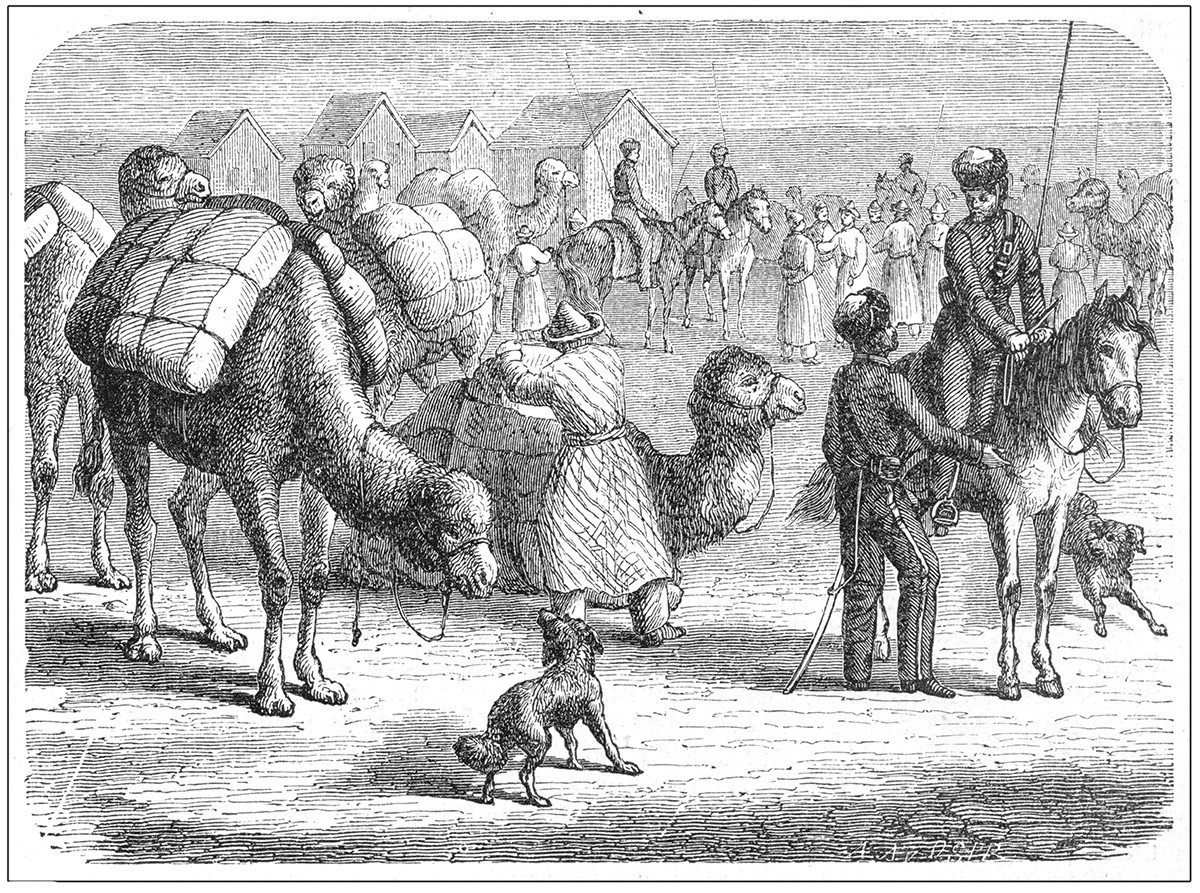

Another popular “Russian” tea type is ‘Russian Caravan’ - owing its name to Russian traders, bringing it all the way from China. The tea is a mixture of a variety of black tea strains with a characteristic smoky flavor. Legend has it that during the long journey (which took more than a year), the tea would become infused with the aroma of bonfires the traders had warmed themselves with at night. In reality, the aroma comes from the keemun tea leaves (Russian Caravan is a blend of keemun, oolong and lapsang souchong). The keemun leaves give it both its smoky flavor and brownish hue. Twinings and Stash Tea sell it today.

One of the most popular “Russian” teas in the world is made by Kusmi, established in 1867 by Pavel Kuzmichev, who was a genius at blending teas. The leaves were purchased in China, while the blending took place in his tea houses in Europe.

Kuzmichev’s most famous tea became the ‘Prince Wladimir’, created in honor of the 900th anniversary of the prince’s birth. After his death in 1908, Kuzmichev’s son Vyatcheslav took over, opening up houses in London to cater to fans of ‘Queen Victoria’ and ‘Windsor Castle’ blends; then Paris, where the company finally settled, shortly before the 1917 Russian Revolution.

Kusmi managed to create a real tea empire, with offices in Germany, the United States and Turkey. However, his son, Konstantin, was not as successful an entrepreneur as Vyatcheslav, and ended up selling Kusmi in 1972 for pennies on the verge of bankruptcy.

The brand name changed hands several times in recent years, until, in 2003, it ended up with the Oreby brothers, who deal in coffee and tea drinks. They decided to restore the Kusmi name’s former glory and, thanks to that, we can again see the brand on store shelves everywhere. Except Russia.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox