“The U.S. is returning to the surface of the Moon, and we’re doing it sooner than you think,” tweeted NASA head Jim Bridenstine last November. It was the official start of the U.S. campaign to win the next race to Earth’s only natural satellite. For the Chinese, however, “official” means more than Twitter. Immediately after this announcement, Beijing launched the first-ever space probe to the dark side of the Moon.

Meanwhile, at a meeting at the Russian parliament, the deputy head of Roscosmos, Russia’s space agency, cautiously suggested that a new Moon race had begun between the three space powers: the U.S., China, and, by default, Russia. Roscosmos has promised to unveil its lunar exploration plans by spring 2019. The last time Russian instruments landed on the Moon’s surface was way back in Soviet-tinged 1976.

Flying to the Moon is not cheap. The 13-year Apollo program (launched in 1961 with the objective of putting a man on the Moon) still holds the record for NASA spending. But it is believed that such outlays will eventually pay for themselves. Lunar research is important for fundamental science, and the Moon is seen as a cosmic service station for expeditions to Mars, a place to stock up on fuel and other resources. Put simply, it is the gateway to deep space exploration.

Like Antarctica, the Moon does not belong to anyone. “[In Antarctica] there is a rule that if someone installs a station by a lake, no one else should do it. The situation is similar on the Moon,” says Lev Zeleny, director of the Space Research Institute under the Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS).

In 1979, the UN adopted the Outer Space Treaty, under which the Moon and its minerals are “the common heritage of mankind,” and no one can claim sovereignty over them. The only snag is that neither Russia, nor the U.S., nor China has ratified it. So disputes over the Moon’s abundant resources are likely just a matter of time. For example, the lunar reserves of the isotope helium-3 (very rare on Earth) could provide humanity with energy for at least 250 years. As noted by Kailasavadivu Sivan, head of the Indian National Committee for Space Research, “countries able to deliver this substance from the Moon to the Earth will control this process.”

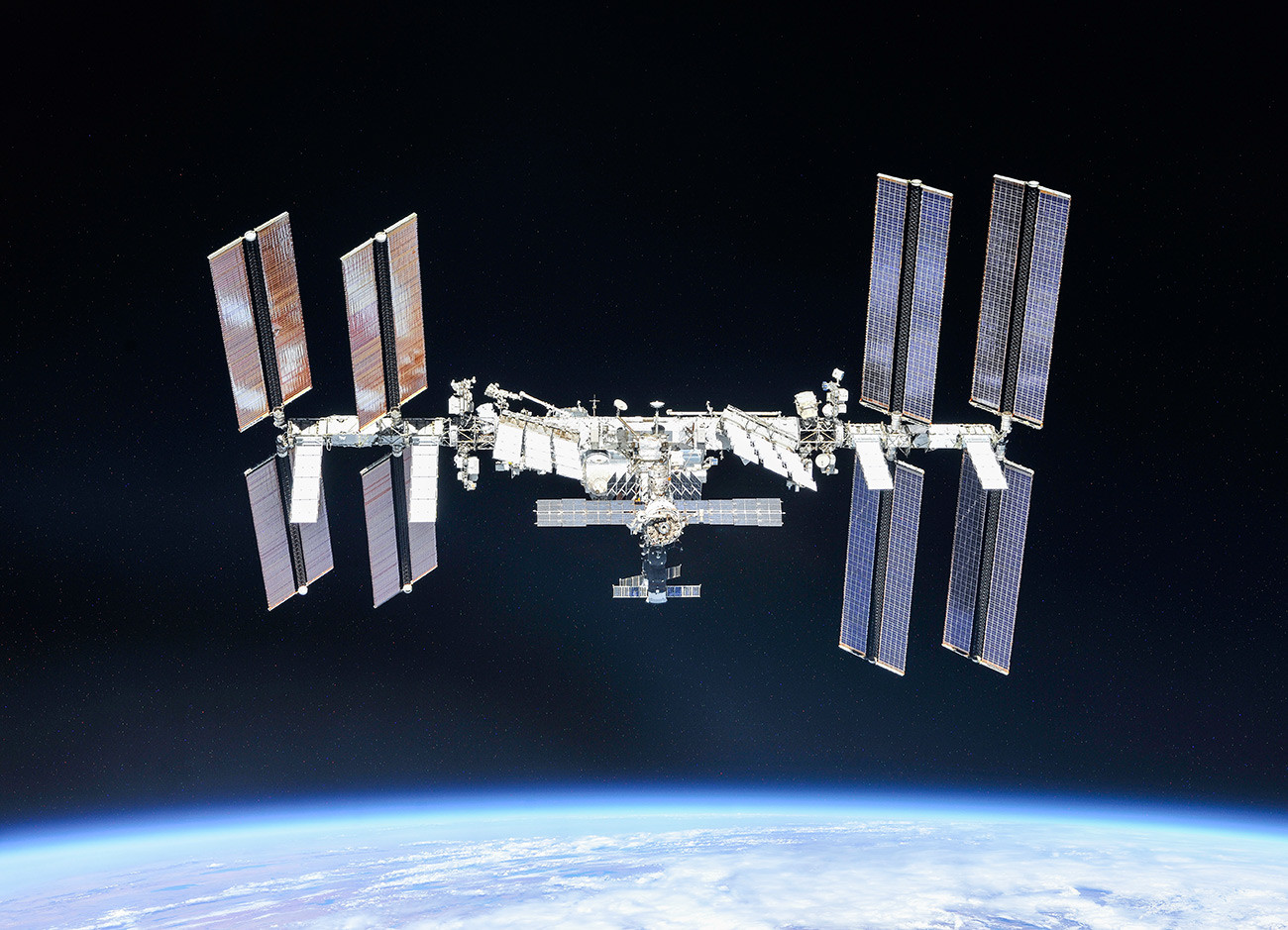

International Space Station

ReutersWhat's more, it is likely that the International Space Station (ISS) will cease to exist in its current form in 2024. About half of its operating costs are presently covered by the U.S. (approximately $2.5 billion annually), and the contract expires in 2024. The Trump administration does not want the U.S. to continue maintaining the station. NASA already has plans to relocate to a near-Moon orbit and to the Moon itself, while the ISS will be handed over to private companies for commercial use. China has never been aboard the ISS (it plans to launch its own station in 2020), meaning that Russia faces a stark choice: fly to the Moon or fall to the ground.

“In any case, the Russian space program is stalling. The problem is that it’s constantly being revised and postponed,” Alexander Shaenko, rocket scientist and co-developer of the Angara-A5 and KSLV booster vehicles, told Russia Beyond.

Russia’s current plans include the first mission to explore the lunar south pole, where frozen water lies under the surface and where the country intends to build a base. Its Luna-27 probe is set to depart for the pole in 2020, with European equipment on board.

That same year, Russia wants to start sending parts of the Russian segment of the ISS to the Moon; these will be used to build a lunar orbital base in the following decade, where regular flights aboard new spacecraft will be made.

It sounds like a good plan, but problems have already arisen. The launch of one of the Russian vehicles, the Luna-25, scheduled for 2019, has had to be postponed for two years. It was due to make the first-ever landing at the lunar south pole (right where the frozen water is), but the RAS decided that preliminary tests were “not sufficiently positive.”

As a result, Russia has already lost one partner, Sweden, which used a Chinese rocket to carry its device for studying the exosphere. There are concerns that more disruptions will follow.

“Developments are forever being aborted. We still haven’t built the new Federation spaceship [in development for 10 years]. It’s rumored that the project will be shut down and we’ll modernize the Soyuz instead. And we still can’t launch the Angara A-5 heavy-lift vehicle,” Sukhoi former constructor Vadim Lukashevich said in conversation with Russia Beyond.

Another cause of Russia’s failures is the loss of Soviet-era technology for launching spacecraft and landing them on extraterrestrial bodies. It has been 40 years since Russia ventured beyond Earth’s orbit, and without practice such skills are lost. The RAS believes that Russia now lags far behind. The guys who knew about interplanetary probes are now either retired or deceased.

China has slowly but methodically developed its lunar program to the level that the Soviets and Americans had in the 1960s and 70s, but currently this level is beyond both Roscosmos and NASA, believes Alexander Shaenko.

For a start, Russia will have to re-engineer the soft landing of lunar probes, and relearn how to operate lunar rovers and deliver soil samples. The process is further complicated by the sanctions: Russia used to purchase around 70% of its astrionics equipment from the U.S., but that channel has been closed off, delaying the process even more.

So is Russia out of the race before it’s properly started? No, says Alexander Shaenko, recalling the Dynamic Albedo of Neutrons (DAN) instrument, which discovered water on Mars and the Moon, and now sits on the U.S. rover Curiosity, examining the water content of the martian soil.

And then there’s the Radioastron telescope, another Russian project of global significance. It supplied the highest resolution images in the history of astronomy and served twice its expected operating life, giving up the celestial ghost only in January this year.

Dynamic Albedo of Neutrons (DAN)

Ignat Solovei/TASSOne other circumstance could buy Russia more time. Trump’s plans to privatize the U.S. segment of the ISS are strongly opposed by the US Senate and NASA Inspector General Paul Martin. “The Americans are afraid that if they stop funding the ISS and switch their attention to the Moon, China will take their place,” reckons Lukashevich. However, this is just one of many reasons why the ISS could remain in orbit for a long time to come.

“Our main problem is a lack of motivation at all levels. Funding is being allocated, but no one seems to believe that [the Moon race] is really necessary,” says Shaenko. “The ISS is still up there, and I suspect that as long as it remains operational, Russia will not be attempting any moonshots.”

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox