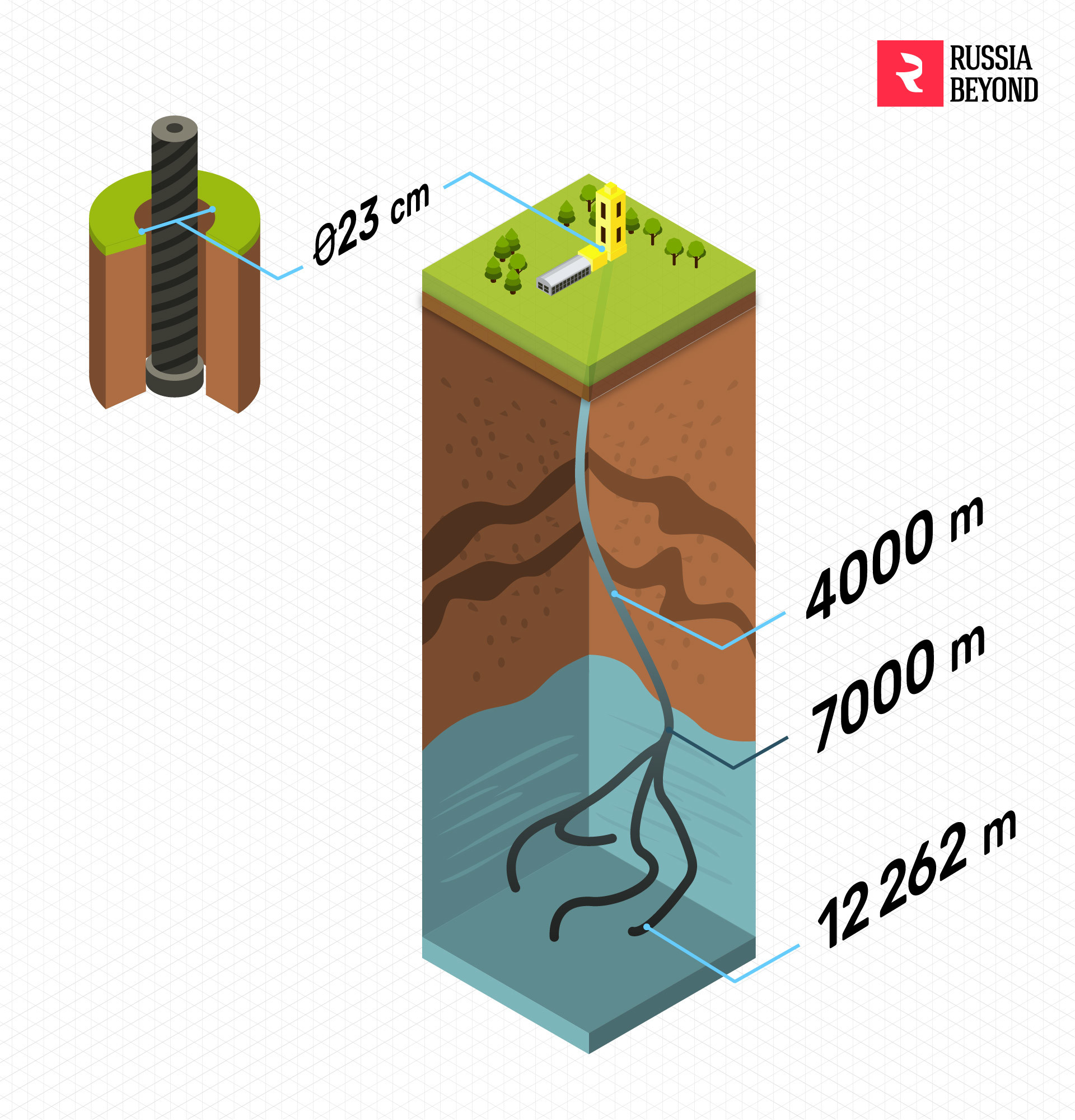

As with every unique place or phenomenon, the Kola borehole (which is 12.262 m[7.45 mi.] deep and 23 cm [9 inches] wide) has a terrifying legend about it, dubbed the “Well to Hell hoax”. According to it, when the drill reached a depth of 12 kilometers, researchers detected a cavity with a temperature of above 1,000 degrees Celsius. They then allegedly lowered a heat-resistance microphone down there, and it recorded the screams of tormented people – supposedly, the drill had reached the cavity where ‘Hell’ was.

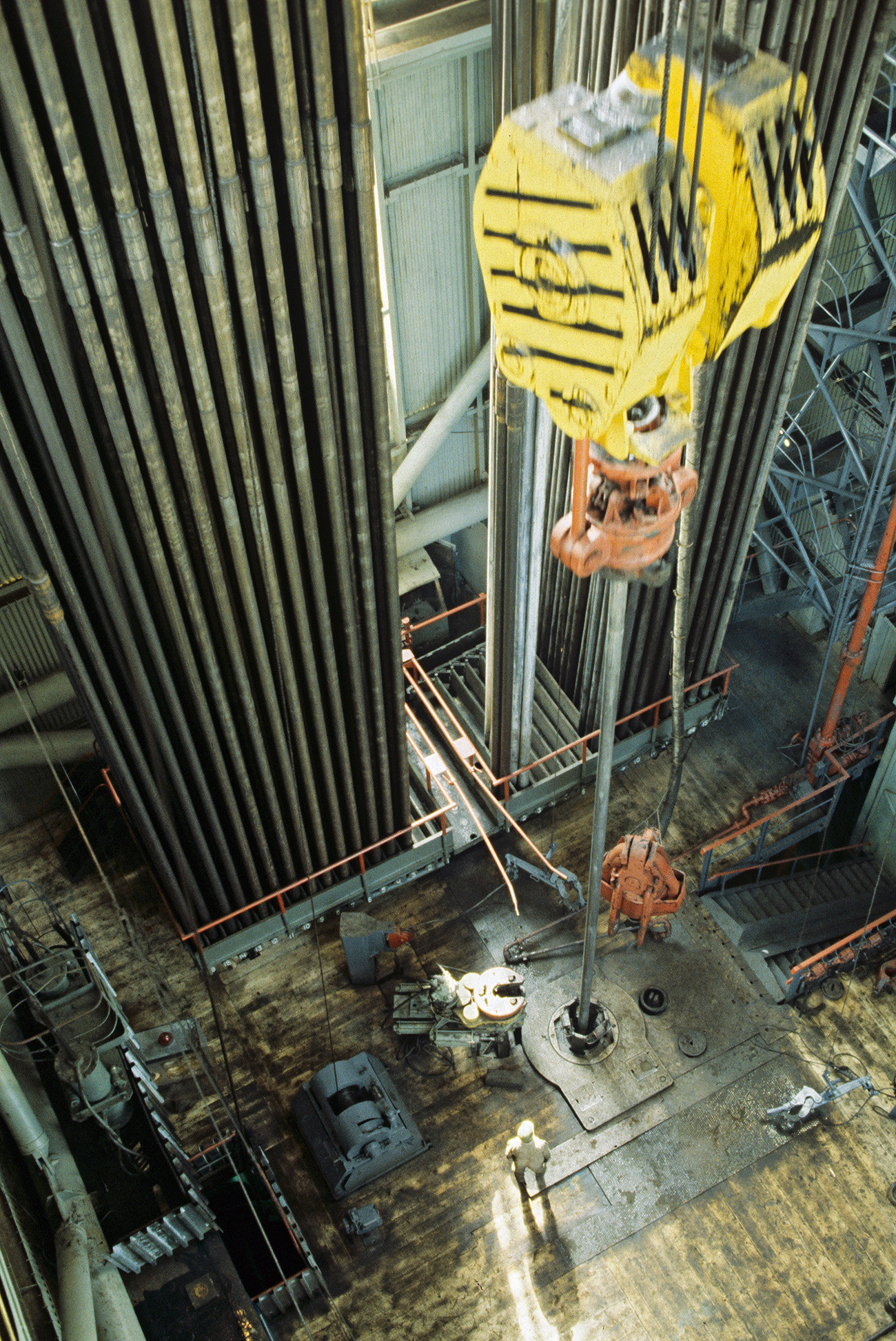

The Kola Superdeep Borehole main facility, the 1970s

Semyon Meisterman/TASSThe inconsistencies are obvious: there are no microphones that can stand the 1,000-Celsius heat; the drilling indeed stopped at 12,262 meters, but the temperature there was about 200 degrees Celsius. However, David Guberman, the head of the boring facility, admitted there was a strange occurrence at the site in 1995…

The main drill.

Alexey Varfolomeyev/SputnikThe Kola Superdeep Borehole is located in the Kola peninsula, belonging to the Murmansk region of Russia. The hole was created as a part of the Superdeep Boring USSR Project. 12 superdeep boreholes were drilled, including the Ural Superdeep Borehole (6 km) and the Yen-Yakhin borehole (8.25 km).

January 1st, 1984. The New Year feast was not a sufficient excuse to stop the drilling.

Semyon Meisterman/TASSThe aim of the project was to inspect the superdeep layers of the Earth. Unlike other boreholes, which were drilled to investigate deposits of oil or gas, the Kola hole was created purely for scientific purposes: to study the inner composition of the Earth’s crust.

Core samples from the Kola hole

Alexey Varfolomeyev/SputnikThe drilling of the borehole continued, with intervals, from 1978 up until 1992. The site was chosen meticulously. The Kola Peninsula is the upper part of the Baltic Shield – a giant bedrock composed of granites and minerals that erupted from below about 3 billion years ago. It’s one of the oldest bedrocks of the Earth, which is why it was so important (and revolutionary, in a way) to study it.

Workers at Kola borehole celebrating reaching a 12-kilometer depth in 1983.

Semyon Meisterman/TASSFor the first four years, everything went smoothly, with the drill reaching a depth of 7 kilometers. Then an extra, enforced drill machine was installed – the drilling apparatus ended up weighing 200 tons. The borehole gradually became more and curvier, because the drill had to circumnavigate harder bedrock and often had to be redirected. By 1983, the depth exceeded 12 km, but in 1984, a disaster happened – the main drill shaft broke, and the boring had to be restarted from 7,000 meters again.

By 1990, the depth had reached 12,262 meters, but the drill broke once more – and for the last time. After this, the boring was stopped, but it also meant the Kola borehole was still the deepest hole in the world. In 1995, five years after the boring had stopped, an explosion of an unknown origin occurred within the mine’s shaft – and even David Guberman said he couldn’t understand what had happened. Regardless, the borehole had already become an enigma by then.

The Kola Superdeep leading scientists Anatoliy Govorukha (front, seated), Semyon Tserikovsky (back, seated), and the head of the facility Alexey Batishschev (back, standing).

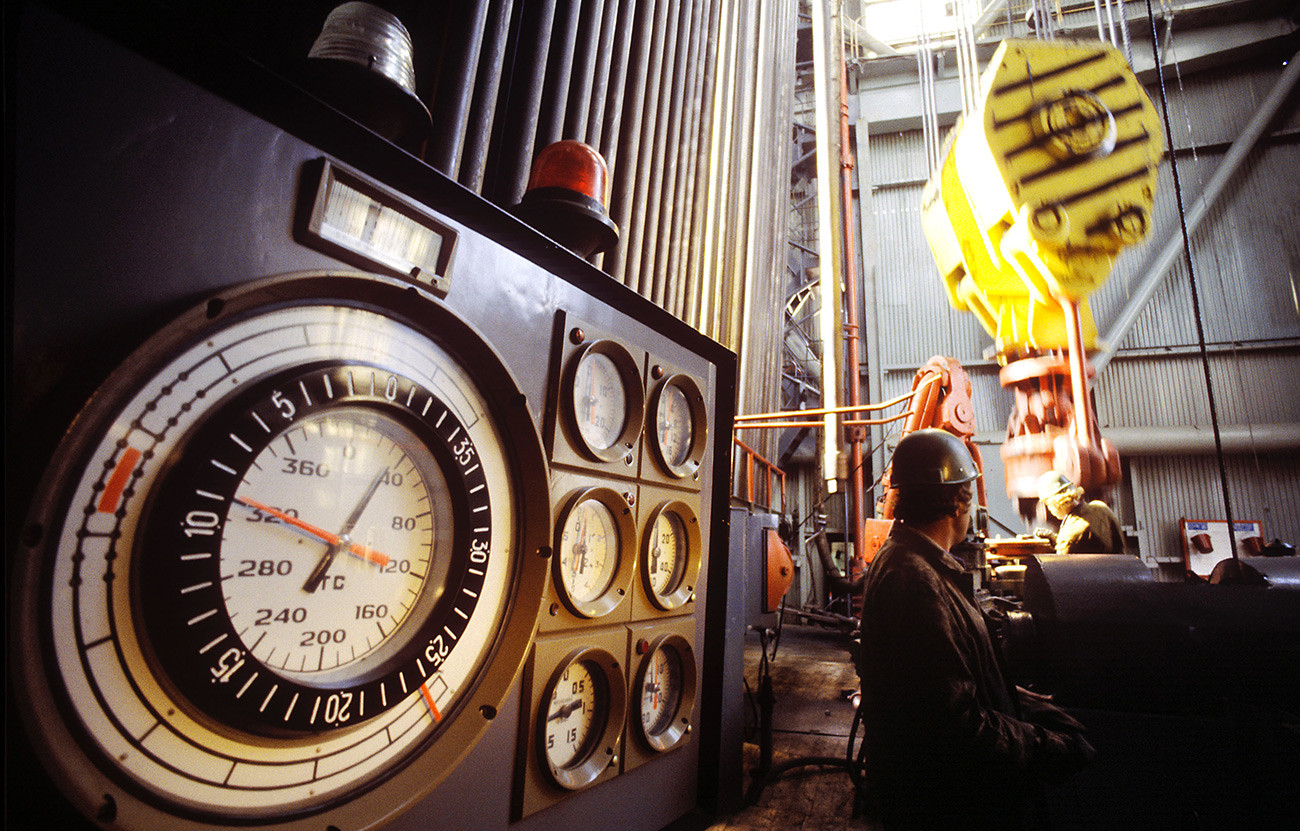

Semyon Meisterman/TASSMeanwhile, the Kola borehole research has overturned all previous conceptions of the Earth’s crust composition. It has contributed significantly to the study of the Moho discontinuity – the boundary between the Earth's crust and the mantle. However, the Kola research didn’t bring any ready answers – it only posed more questions. The most obvious finding was that under 4 kilometers, the temperature began to rise dramatically, reaching over 220 C at 12 km deep.

Gauges at the Kola borehole facility.

Alexey Varfolomeyev/SputnikCurrently, the site of the Kola borehole is in pieces. The facility is abandoned and has been dismantled by locals. The 23-centimeter wide borehole is now sealed with a 12-screw metal lid, while the Kola borehole science facility was officially liquidated in 2008.

What's left of the facility as of 2012

Bigest (CC BY-SA 3.0)If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox