After the Crimean War in 1856, the Russian Black Sea Fleet was defeated, the state coffers were depleted and, according to the Treaty of Paris, Russia was no longer allowed to have a fleet in the Black Sea.

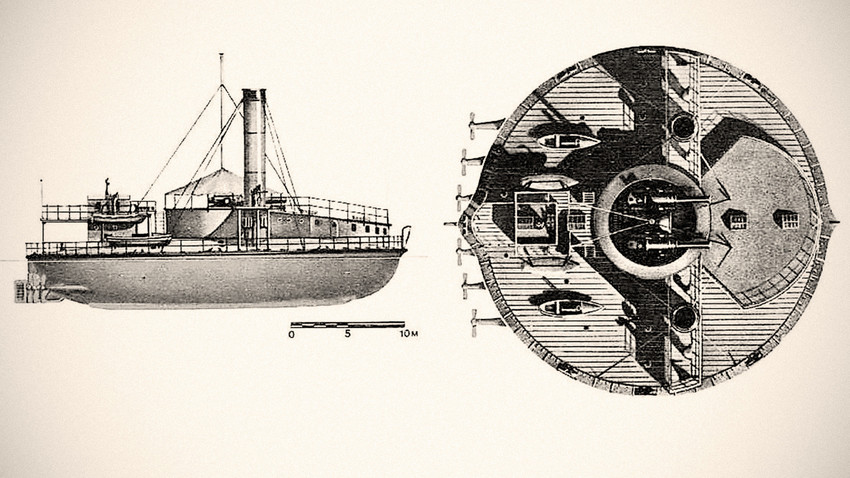

However, the Naval Ministry was not prepared to leave Sevastopol undefended or, indeed, put up with the imposed restrictions. Then Admiral Andrei Popov came up with a proposal to build a circular ship for the coastal defense of Sevastopol. The main reason for this unusual idea was a down-to-earth desire to save money.

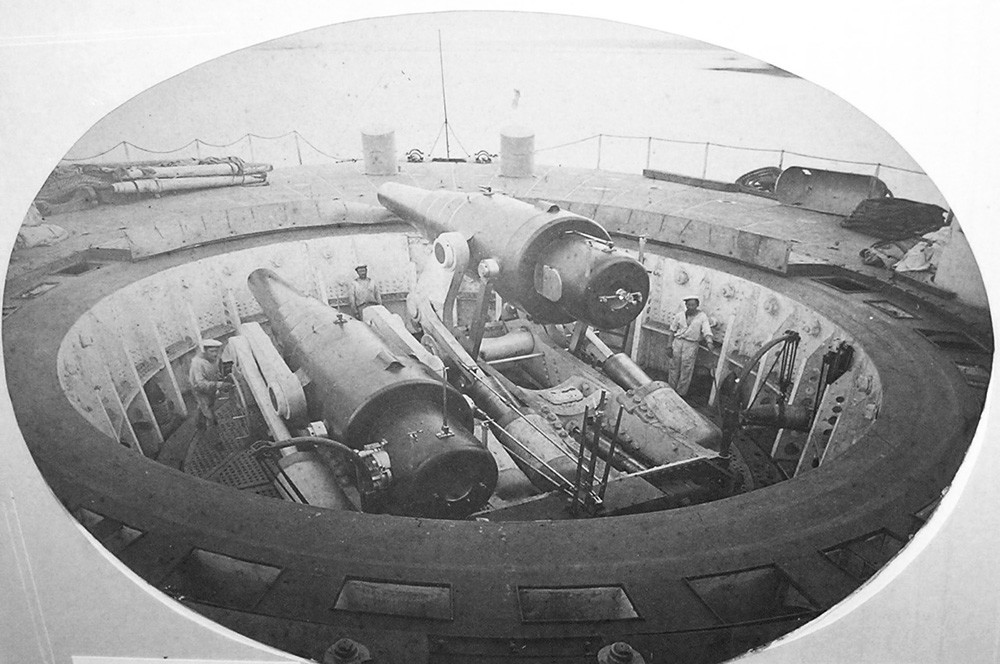

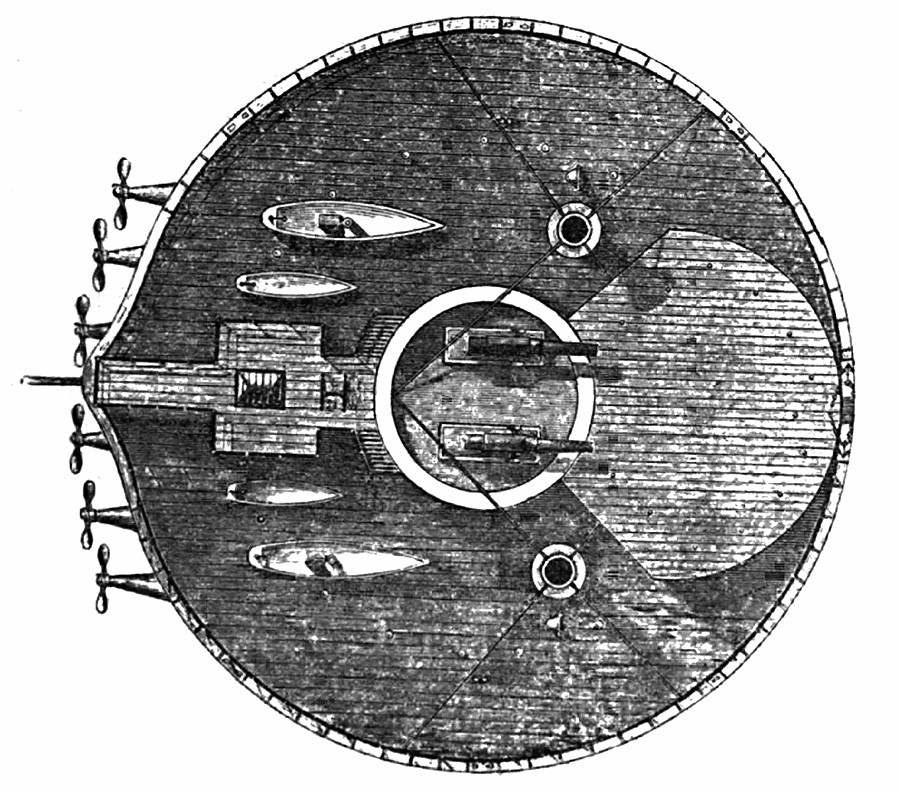

In addition, a warship with a circular hull could carry super-large (and super-heavy, from 21 tons) guns. Popov was convinced that any enemy that would dare to attack the Russian base would do it only with the largest caliber guns available. And while an ordinary ship carrying such heavy guns begins to roll when it delivers a broadside, a ship whose width and length are the same, i.e. a circular ship, would not have this problem.

Finally, circular ships offered a tricky way to circumvent the restrictions imposed by the Treaty of Paris. “Without any stretching, circular ships can be classified as floating fortresses and will therefore not be listed as fleet ships,” Popov wrote in a cable to the ministry.

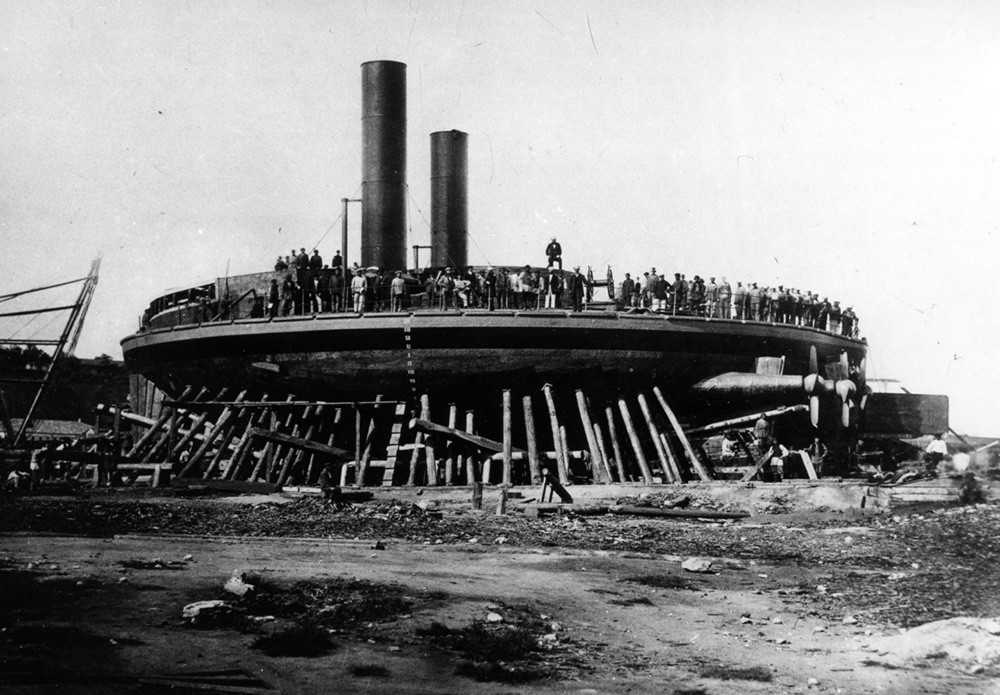

The Naval Ministry found Popov’s idea reasonable. Furthermore, the restrictions of the Treaty of Paris were lifted in 1871, which meant that a circular ship would not have to be classified as a fortress any more. The same year, Emperor Alexander II approved a project to build the first “popovka” - as he had nicknamed the ship, after the designer - the battleship ‘Novgorod’, with a diameter of almost 30 m.

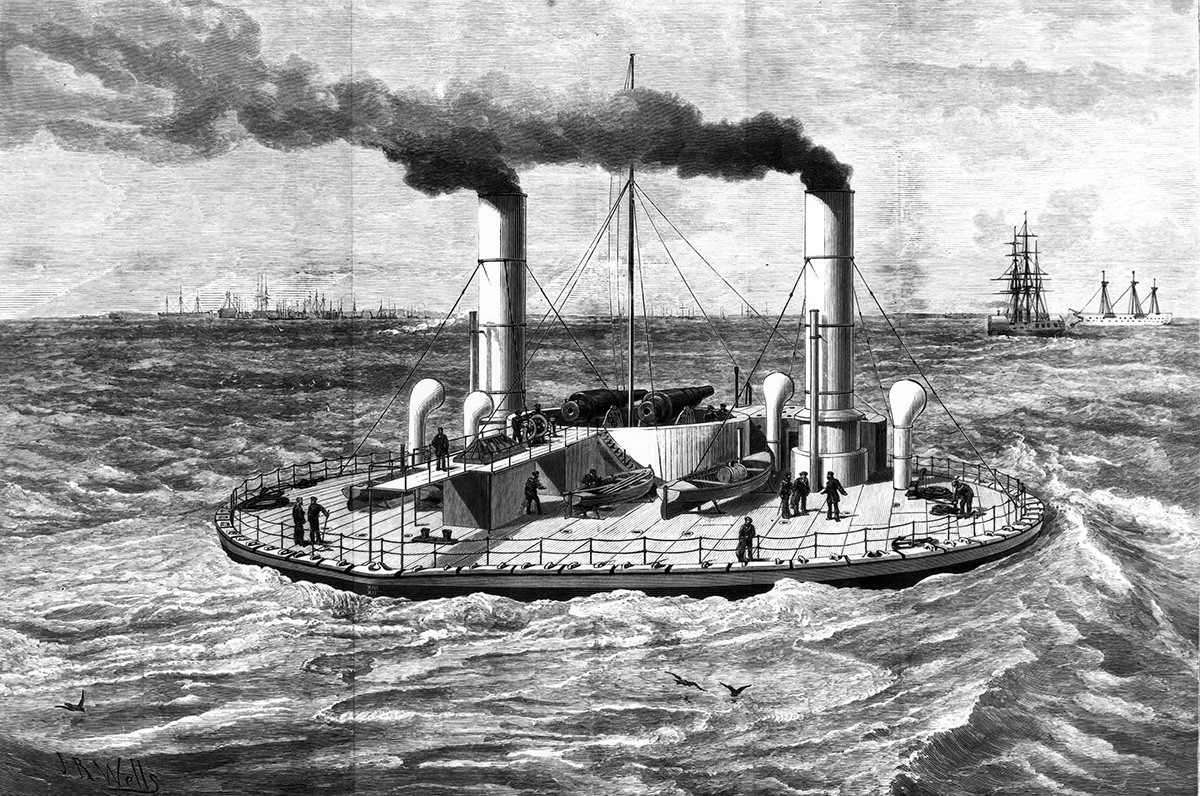

The deck of the Novgorod circular ironclad Illustration from Eardley-Wilmot: The Development of Navies

Capt Sydney Eardley-WilmotThe emperor ordered that the battleship Novgorod serve as a basis for building 10 more similar circular ships, which were planned as a starting point for restoring the entire Black Sea Fleet. However, in reality, only two circular warships were ever built: the second was called ‘Vitse-Admiral Popov’.

The “popovka” could indeed carry the most powerful weapons of the time, but it was very slow.

That became strikingly obvious during the war with Turkey in 1877. Practically throughout the entire war, both ships were used for defensive purposes. But when – just once – they were required to go into battle, the “popovkas” simply could not catch up with the Turkish ships (although those were inferior to them in combat power). That incident was reviewed by a special commission, which came to a disappointing conclusion: circular ships were unable to fight away from the coast.

In fact, the “popovkas” were never intended for sea racing. Back at their design phase, Popov said that they were not suitable for long-distance sea navigation, but “were quite applicable for the purposes of coastal defense”. However, the ministry must have really wanted to see the “popovka” as a full-fledged warship, which it could never be.

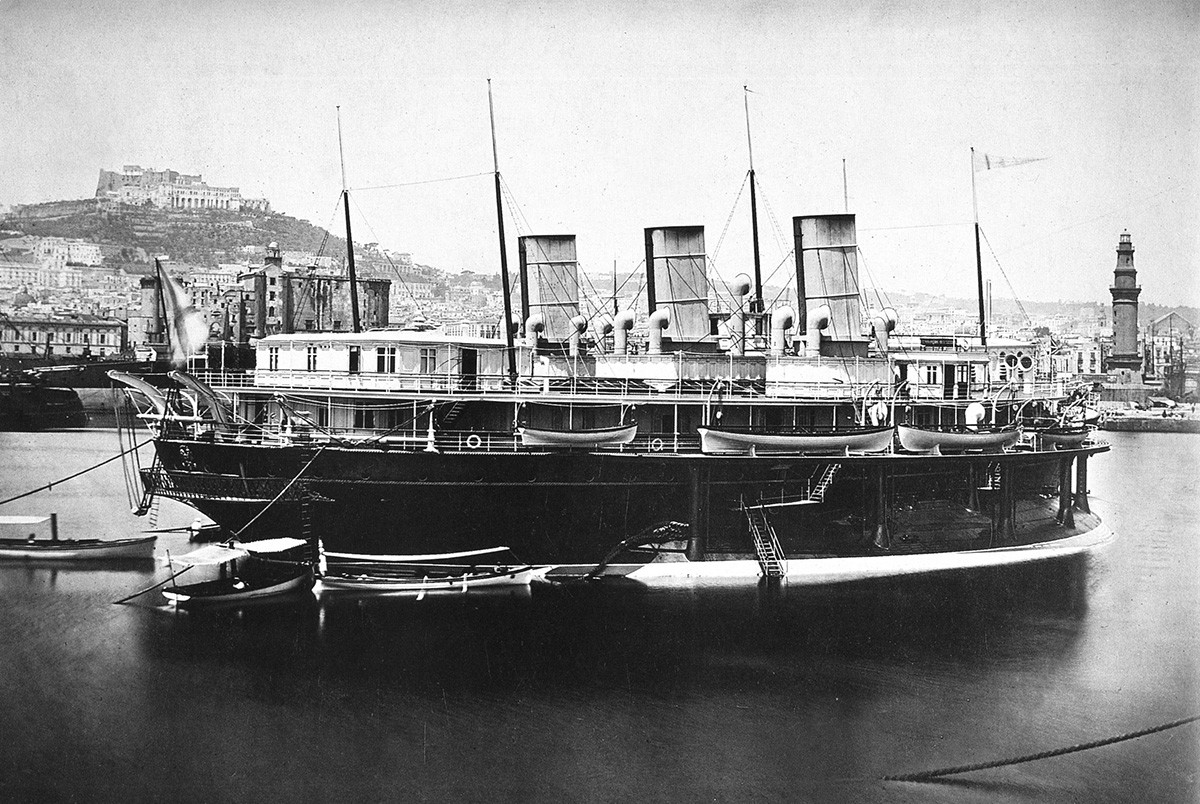

Imperial Russian yacht Livadiia.

Archive photoHowever, even after the military fiasco, Popov did not abandon the idea of circular ships and proposed making a circular yacht for Alexander II. The emperor agreed, but on one condition: the yacht should be twice as fast as the battleships, and, of course, be suitable for sea navigation.

The imperial yacht, called ‘Livadia’, was assembled in England, and its transportation to Sevastopol was to become a quasi sea trial for it. However, the yacht got caught in a storm and its hull was damaged. The official conclusion that the hull was too weak sounded the death knell for the new type of ship.

When Alexander III ascended to the throne, the era of circular ships came to an end. The Naval Ministry was reorganized, and Popov was removed from “developing a circular Russian ship architecture”. Although later, in 1891, he was promoted to the rank of admiral, Popov no longer took any real part in the affairs of the Navy.

The two existing circular battleships were ranked as coastal defense and remained in service until 1903. The imperial yacht suffered a less enviable fate. Its furniture and fittings were gradually removed to warehouses, after which the luxury yacht was turned... into a plain, lighter ship for transporting coal.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox