Japanese newsreels from 1961 show long waiting lines at vaccination stations. Worried-looking women are holding babies in their arms and older children stand next to their parents, while members of medical center staff are recording everyone who has received the vaccine. The vaccine was not injected, but taken orally: Children swallowed the medicine from spoons and were no longer able to catch poliomyelitis (commonly known as polio) - a dangerous disease that affects the gray matter of the spinal cord and can cause paralysis of the limbs and even cause death.

The polio vaccine was long awaited in Japan - 13 million doses were imported from the Soviet Union in the summer of 1961. Prior to that, outraged mothers, fearing for the wellbeing of their children, had protested in the streets for months and besieged the Ministry of Health and Welfare - the government was very reluctant to buy the vaccine from Moscow.

But how did it happen that the USSR found itself at the forefront in the fight against polio?

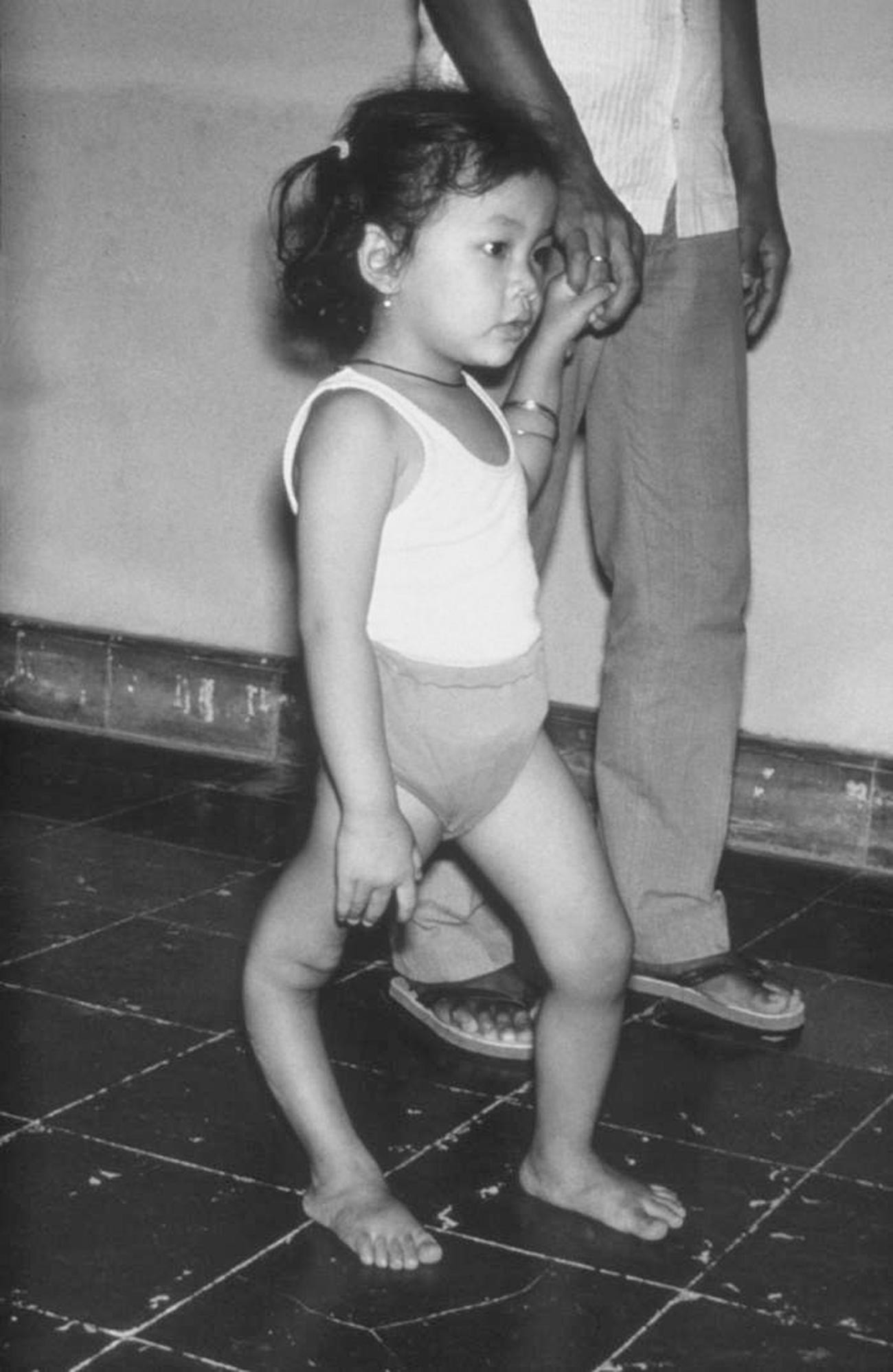

A girl with a deformity of her right leg due to polio

Archive photoPolio, or infantile spinal paralysis, had been known to humankind for a long time. It is usually a disease of children. “A child born healthy becomes disabled overnight. Could there be a more frightening disease?” The Akahata newspaper cited one of the alarmed Japanese mothers as saying in June 1961.

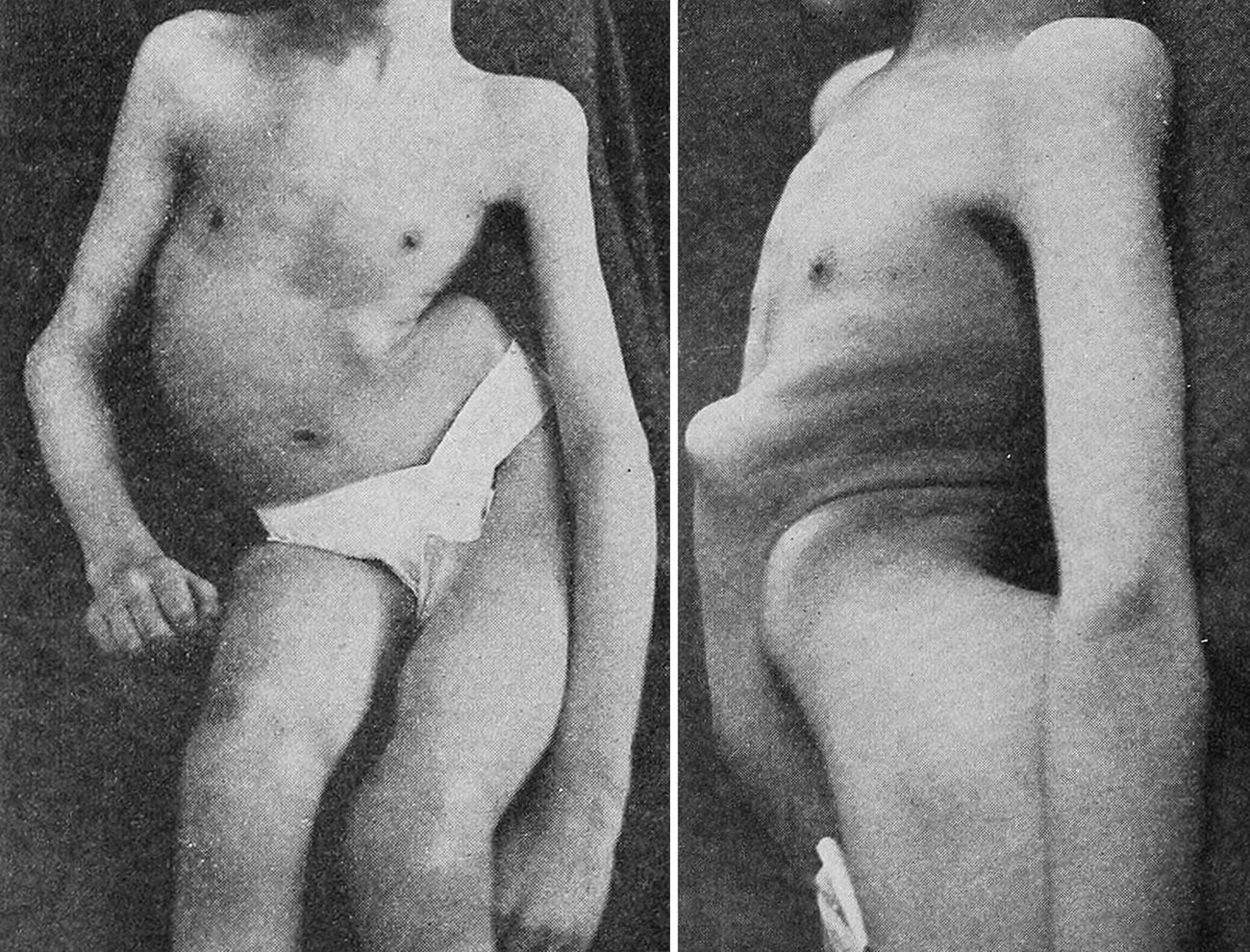

A boy with polio

Archive photoAfter World War II, as cities and population density grew, polio assumed menacing proportions: Outbreaks became more frequent, affecting more and more people. The USSR was no exception - while 2,500 cases were recorded in 1950, by 1958 there were more than 22,000.

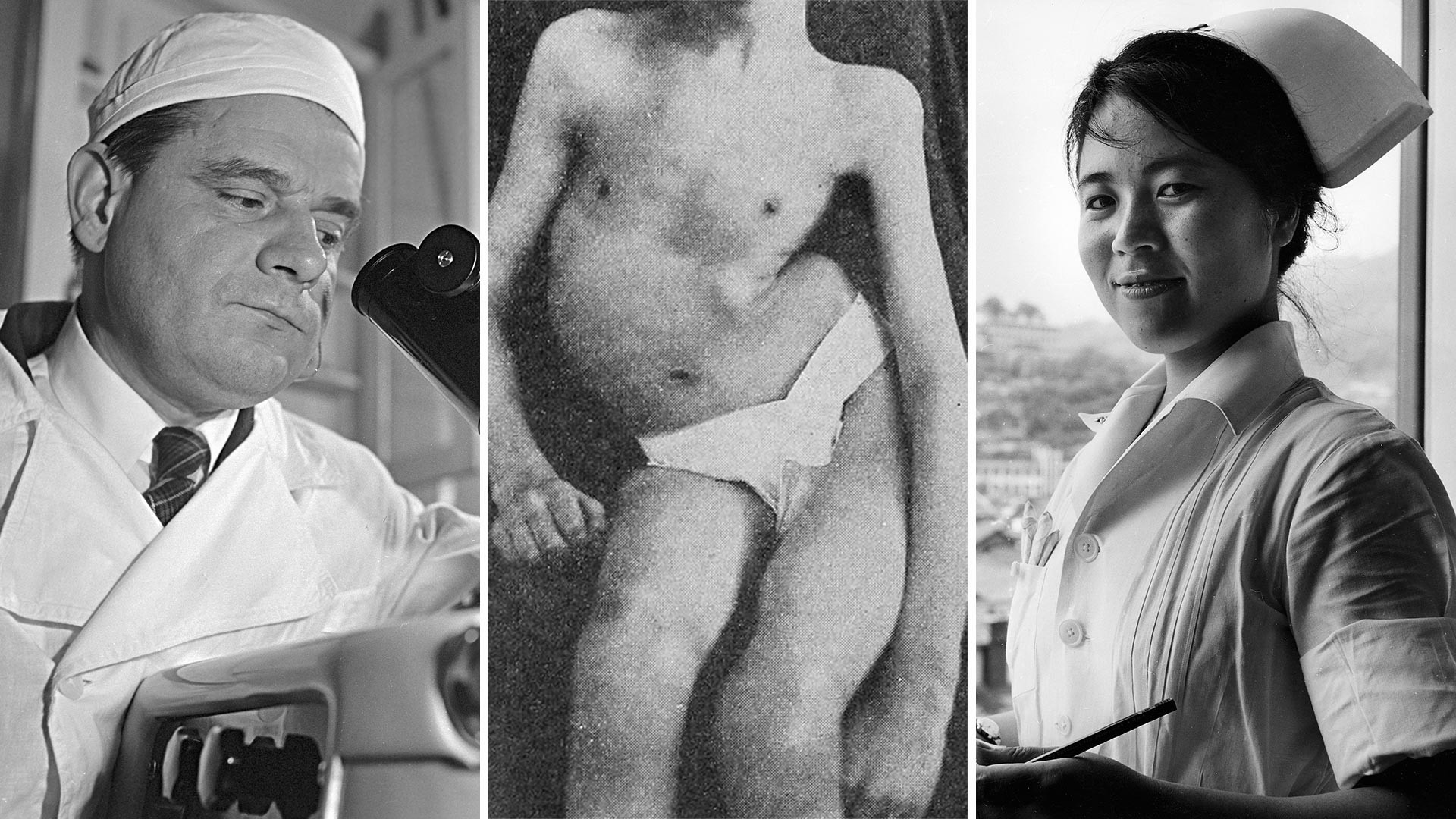

Mikhail Chumakov, director of the Poliomyelitis Institute and associate member of the Academy of Medical Sciences

I.Golubchin/SputnikIn 1955, the Poliomyelitis Research Institute was set up in the USSR. It was headed by Mikhail Chumakov (1909-1993), a scientist with a wealth of experience and the Soviet Union’s best virologist. Still, it was not Chumakov, but an American colleague, who worked to develop the vaccine. To be more precise, two American scientists - Jonas Salk and Albert Sabin - developed two different types of vaccine. Salk used “killed” polio cells, while Sabin, jointly with his colleague Hilary Koprowski, employed live polio virus. Urgent action was needed.

American scientist Albert Bruce Sabin, developer of the polio vaccine

David Sholomovich/SputnikThe American government approved Salk’s inactivated (“killed”) vaccine and it was this type that was first tested and purchased around the world, including in Japan. The USSR, too, trialled the Salk method, but was not happy with it. “It became clear that the Salk vaccine was not suitable for a nationwide campaign. It proved to be expensive, at least two doses were needed and the effect was far from 100 percent,” recalled Mikhail Chumakov’s son, Pyotr, also a scientist.

Russian scientists visiting the U. S. watch Dr. Jonas Salk administer a shot of his anti-polio vaccine to Paul Anolik,9

Getty ImagesDespite the Cold War and political confrontation between the U.S. and the USSR, the two countries’ scientists continually collaborated: Mikhail Chumakov traveled to America and maintained contacts with Jonas Salk and Albert Sabin. The latter gave Chumakov the necessary strains for the production of the “live” vaccine - as Pyotr Chumakov recalled, “it all passed off without formalities - my parents brought the strains back literally ‘in their pockets’”.

A “live” vaccine based on the Sabin process was produced in the USSR and successfully tested. A factor in this was the form which Chumakov selected for the vaccine - it was decided to produce it as candies, so that children did not have to fear being injected with a needle. Trials “in the field” passed off with flying colors: In 1959, the “live” vaccine was used to rapidly halt a severe flare-up of polio in the Baltic republics. Subsequently, the USSR switched fully to the “live” vaccine and polio was defeated en masse in the country.

A girl holding a vaccine capsule in her teeth at the Institute of Poliomyelitis and Encephalitic Infections.

Ettinger/SputnikIn his correspondence, Sabin jokingly referred to Chumakov as “General Chumakov” for organizing such a rapid and massive anti-polio campaign.

Towards the late 1950s, the situation with polio in Japan was not as acute as in many other countries, with 1,500-3,000 cases being registered every year. For this reason, the government paid little attention to combating the disease - it was believed that the Salk vaccine doses being imported from the U.S. and Canada (in modest volumes) would be sufficient to solve the problem.

“Alongside government inaction, the majority of Japanese scientists were also failing to focus on the problem of polio. Our work met with perceptible resistance,” according to Masao Kubo, one of the organizers of the campaign to combat infantile spinal paralysis. “[We were told:] ‘But it only affects a thousand or two thousand people or so. Is it worth making a fuss over it?’” Many doctors approached by parents failed to diagnose polio in time, as a result of which children died or ended up being disabled.

In 1960, the number of detected cases of polio sharply increased in Japan to 5,600 - 80 percent of them children. There weren’t enough doses of the Salk vaccine to conduct a large-scale vaccination program, and, what was more, its efficacy was being called into question. Meanwhile, Japan’s own vaccine projects were proving unsuccessful. Protests were breaking out throughout the country, as by then, Sabin’s “live” vaccine had been trialled outside the USSR and its efficacy demonstrated.

A young boy in leg braces, a victim of polio

Getty ImagesThe parents of sick children demanded that the “live” vaccine be imported, but the authorities were in no hurry to meet these demands. Officials doubted whether the vaccine would be effective for Japanese people, the government was unwilling to cooperate with the “Reds” (Japan, at the time, remained a loyal ally of the USA) and the pharmaceutical companies were content with their contracts with North American firms.

Nevertheless, a large-scale national movement consisting of parents, many doctors and political activists was formed in 1961. They all demanded that the vaccine be purchased from the USSR and a mass vaccination be carried out. As researcher Izumi Nishizawa notes in an article about the movement, people gradually switched from the idea of “a vaccine for my child” to “a vaccine for all children in the country” and this enabled previously disparate activists to join forces and to put up a united front.

Scientists of the Institute of Poliomyelitis and Viral Encephalitis at Soviet Academy of Medical Sciences (now known as Mikhail Chumakov Institute) are creating a vaccine against polio

Lev Ustinov/Sputnik“We ask for the ‘live’ vaccine to be provided as rapidly as possible! Children are being stalked by this invisible virus every day. Do you not have children yourselves? Has the required research not already been done abroad? It’s not because the pharmaceutical companies are displeased, is it?” The Akahata newspaper wrote, quoting parents’ demands. In parallel with the protests, research was also being done: Masao Kubo, who was a scientist from the Japan Doctors Association, paid a visit to Moscow from December 1960 to January 1961, during which he verified the reliability of the Sabin vaccines being manufactured in the USSR and also their lower price, in comparison with other countries. The government had fewer and fewer reasons left against importing them.

These reasons ran out altogether when, on June 19, 1961, mothers protesting in Tokyo entered the Ministry of Health and Welfare building - the police could not stop the women - and presented their demands to officials face to face. On June 22, the ministry caved in and it was announced that the USSR would supply Japan with 13 million doses of the “live” vaccine. Deliveries were rapidly organized through the intermediary of the Japanese company, Iskra Industry. “Older people will no doubt remember the Aeroflot airliner being welcomed at Haneda airport by crowds of thousands of people,” wrote journalist Mikhail Yefimov, bureau chief of the Novosti Press Agency in Japan for more than 10 years.

Scientists of the Laboratory for Monkey Experiments examine a monkey before the experimental vaccination in the Institute of Poliomyelitis and Viral Encephalitides of Academy of Sciences of the USSR

Vasily Yegorov/TASSThe vaccination program produced rapid results and, by autumn, the outbreak of the epidemic in Japan had petered out and a few years and several vaccination campaigns later, the disease was practically eradicated in the country. The vaccine’s inventor, Albert Sabin, as well as Mikhail Chumakov, without whose efforts it would not have gained popularity throughout the world, need to be thanked for this - as well as, of course, the thousands of Japanese mothers, doctors and activists who demanded from their government that it set aside politics for the sake of their children’s futures.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox