It’s 1955 and we’re at NII-4 in Bolshevo, Moscow Region, a secret military research institute that deals with calculations for ballistic missiles. One of its spacious rooms is occupied by “dreamers” – a nickname given to the scientists who had the task of considering possible problems during space flights. No one had gone to space yet, only 10 years had passed since the end of World War II.

From time to time, the “dreamers” argue noisily: a man can’t be sent to space – he’ll burn when he’ll be coming down to Earth, he’ll “inflate” in zero gravity or he’ll be torn apart; the radiation will kill him and so on. Sometimes, people from other departments run up to those shouting and, twisting a finger at the temple, quietly shuts the door to these sci-fi fanatics.

But, only two years pass and the “dreamers” become the ones working on the most ambitious project of humanity: launching the first artificial Earth satellite into space.

Before approaching the idea of launching an artificial body into Earth’s orbit, something that would deliver it there had to be designed – a rocket.

“The story of creating the first satellite is the story of a rocket. The rocket technology of the Soviet Union and the U.S. had German roots,” Boris Chertok, a design scientist, notes.

After World War II, Soviet inventors gained access to the captured German equipment, in particular the ‘V-2’ – a rocket with an operational range of 320 kilometers that performed the world-first sub-orbital spaceflight. They studied it meticulously and designed a range of Soviet rockets on its basis. The name of the Soviet space program leader, Sergei Korolev, was, at this time, strictly classified (his career is unusual, too: in 1938, he was sentenced to 10 years in prison camps and then transferred to the so-called sharashka – a secret design bureau for convicted scientists).

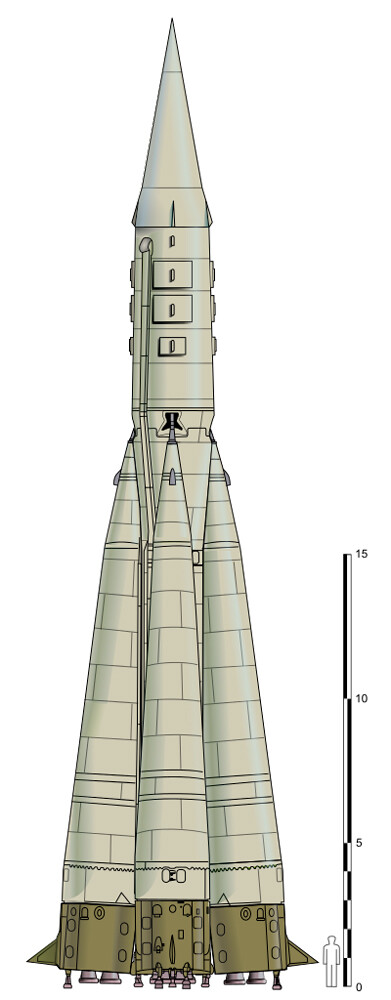

First version of the R-7, tested in 1957

Heriberto Arribas Abato (CC BY-SA 3.0)In 1954, under his leadership, the Semyorka emerged – the ‘R-7’ rocket with an operational range of up to 9,500 kilometers. “When, in 1957, the R-7 ballistic missile was launched from the ‘Tyuratam’ cosmodrome [it was later renamed ‘Baikonur’] and struck its target on a proving ground in Kamchatka, it became clear that we had a carrier to launch a satellite to orbit. To be honest, before that, I didn’t believe that all 32 engines of the rocket could start at the same time and work as planned,” academician Georgy Uspensky recalled, one of the “dreamers” from that noisy room.

The attitude towards the group of “dreamers” changed immediately. They were tasked with the creation of the first satellite with the name ‘Object D’. Its mass should have amounted to 1,000-1,400 kilograms, with 200-300 kilograms more for research equipment. One of the satellite design variants even included a container with a “biological payload” – an experimental dog. In other words, it was not the tiny ‘Sputnik’ but a heavy machine that they hoped to carry to orbit with the help of the R-7 in 1957-1958.

Sergei Korolev (second from left) among his team

From the funds of the State Historical Museum/SputnikHowever, soon it became apparent that meeting such deadlines for this time-consuming project was impossible. The work dragged on. Besides, the USSR learned that similar work was underway in the U.S. – the launch of the ‘Minimum Orbital Unmanned Satellite of Earth’ was planned for the same time. Then, Korolev made the decision to abandon the “heavyweight” in favor of a simple and light device with only two beacons.

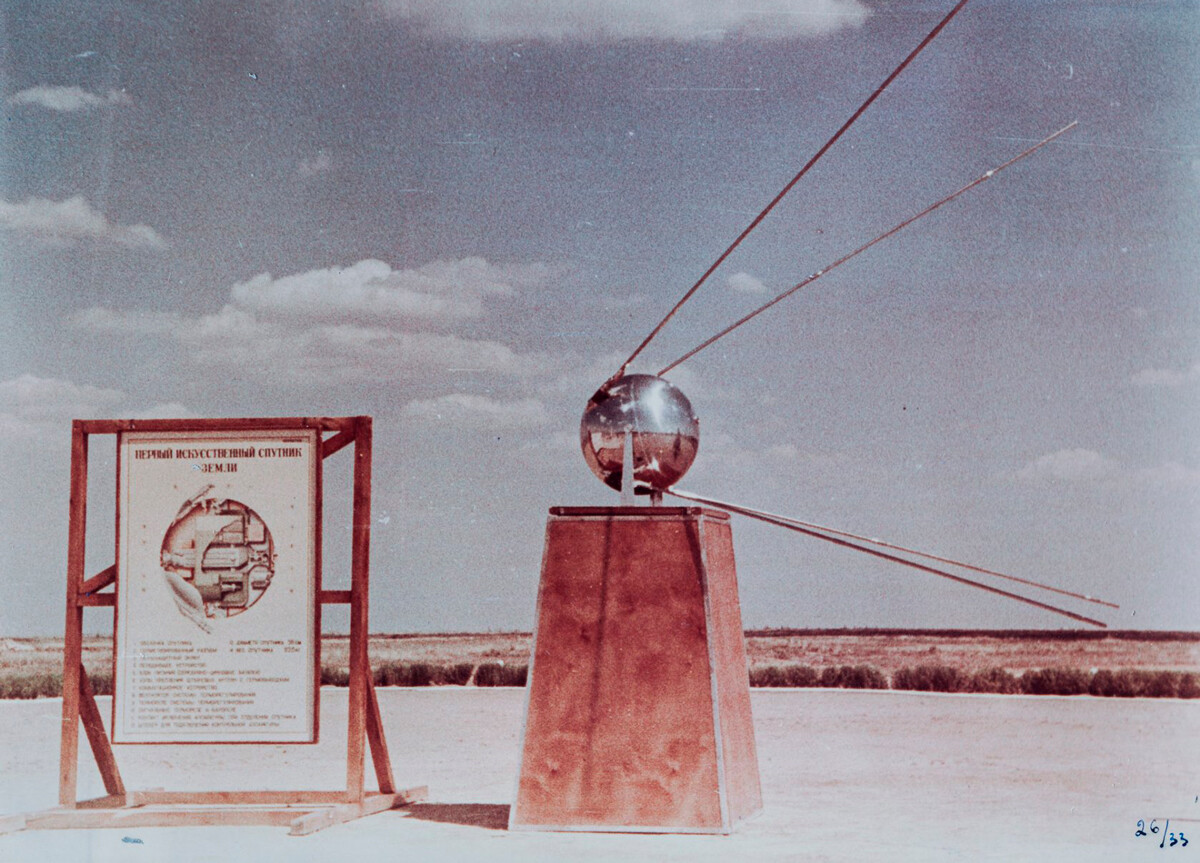

From the outside, the satellite looked like a sealed aluminum ball with four antennas, with a diameter of 58 centimeters and a weight of just 83.6 kilograms. Two beacons fit inside. In addition, the transmission range of the beacons was picked so even radio amateurs could follow the satellite. Many of them remembered the distinctive sound “beep-beep-beep” when Sputnik flew over them.

Sputnik-1, a model.

Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation / mil.ruThe satellite was designed at record speeds. “People didn’t leave their workplaces for days, they slept on folding beds in Korolev’s design bureau! The first satellite, of course, was quite simple in its design and its hardware. A sensor was installed in it that was needed for the research – how radio waves travel through the atmosphere. We didn’t even know that back then,” Uspensky said.

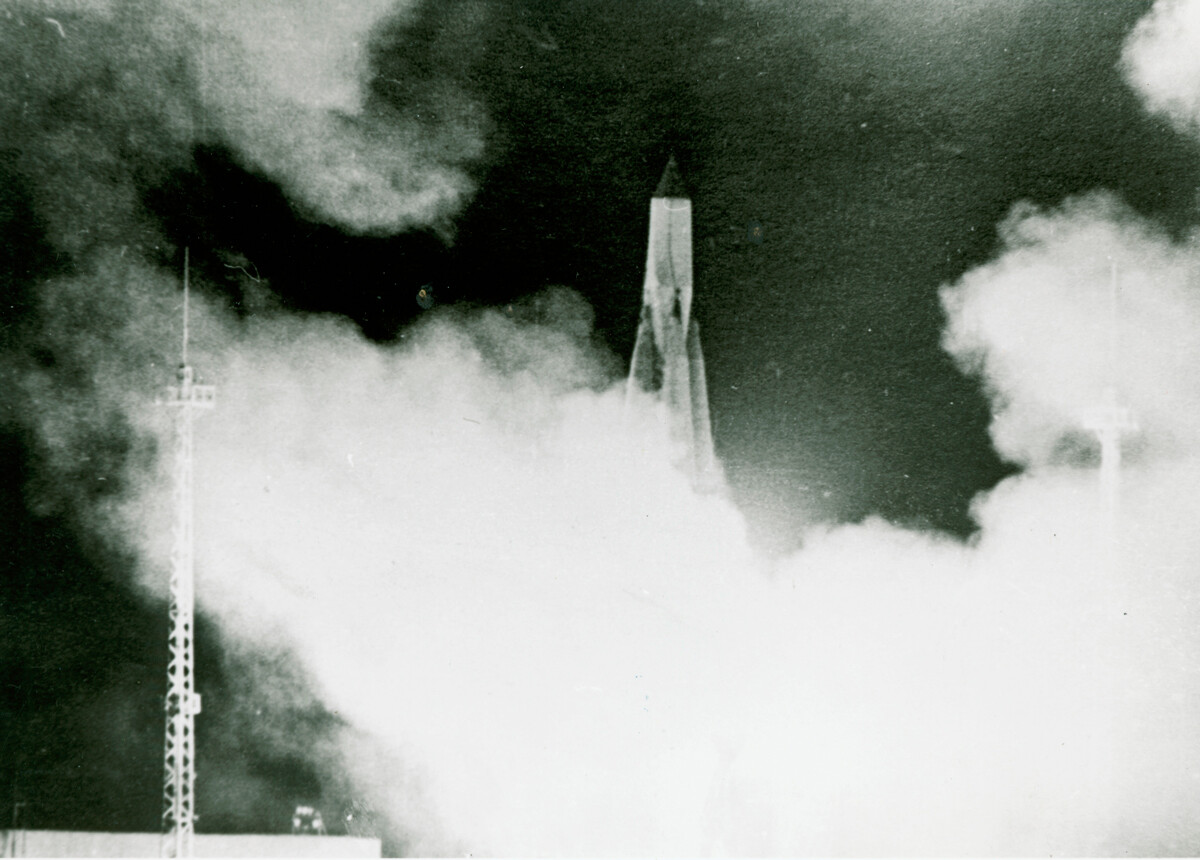

In the end, between the successful test of the R-7 in August, 1957, and the launch of the satellite, only two months had passed. On October 4, 1957, at 22:28 Moscow time, the launch vehicle with the satellite was sent to space.

Postage stamp

Public DomainHumanity’s first satellite didn’t last long – 92 days, until January 4, 1958. It managed to complete 1,440 rotations around the Earth and its beacons worked for two weeks after its launch. However, due to friction in the upper atmosphere, it lost speed, entered the dense layers of the atmosphere and burned up.

The news about the launch of the Soviet satellite had a bombshell effect. Journalists from all across the world called it the “universal shock” and “not only a large scientific achievement, but also one of the greatest events in the history of the whole world.” It was called ‘Red Moon’ in the American press.

Many back in those days tried to see Sputnik in the rays of the rising or setting sun. In fact, they could only see the rocket’s central unit (until it burned up), a small ball less than a meter in diameter. But even the leading Soviet newspaper ‘Pravda’ believed that this was insignificant and urged the people of the entire world to look up to the sky.

Launch of Sputnik-1 spacecraft from Baikonur Cosmodrome

RSC Energia / TASSBut the launch had not only scientific, but also a large political meaning. On October 4, it became clear that the Soviet Union had a multi-stage intercontinental missile, against which air defenses were powerless. It changed the entire system of international relations.

Read more:The Russian rover that made it to Venus

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox