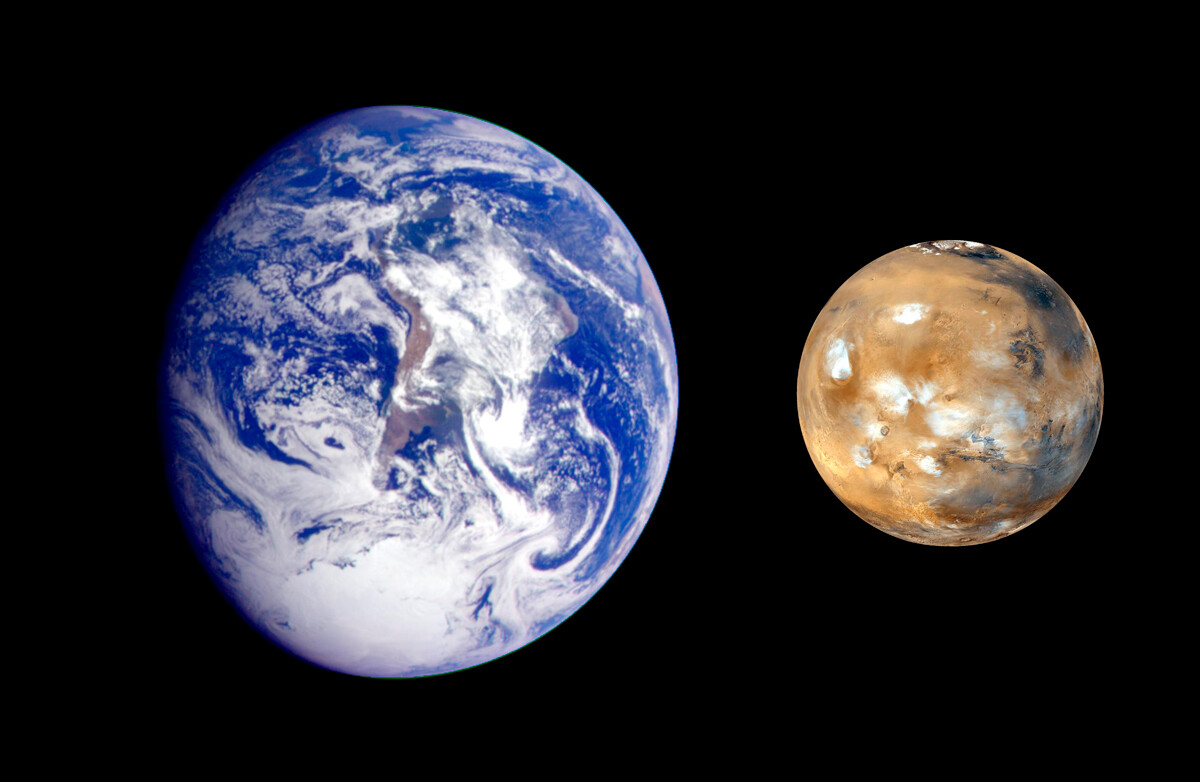

After Yuri Gagarin’s space flight and the Moon landing, the space race only continued to gain momentum. The USSR and the U.S. devised plans of not just further exploration of Earth’s satellite, but also of the other planets of the Solar System. The Soviet martian program became possible in many ways, thanks to the successes of the lunar missions. But, it was, to say the least, a bit more complicated with Mars.

The Soviet attempts to reach Mars began in 1962, just a year after the pioneering Gagarin flight.

The task of the first martian spacecraft ‘Mars 1’ was to assume a flyby trajectory (meaning to send back information about the planet while simply flying past it and not even entering its orbit). And it managed to do that. For the first time in the world. However, soon, contact with the spacecraft was lost.

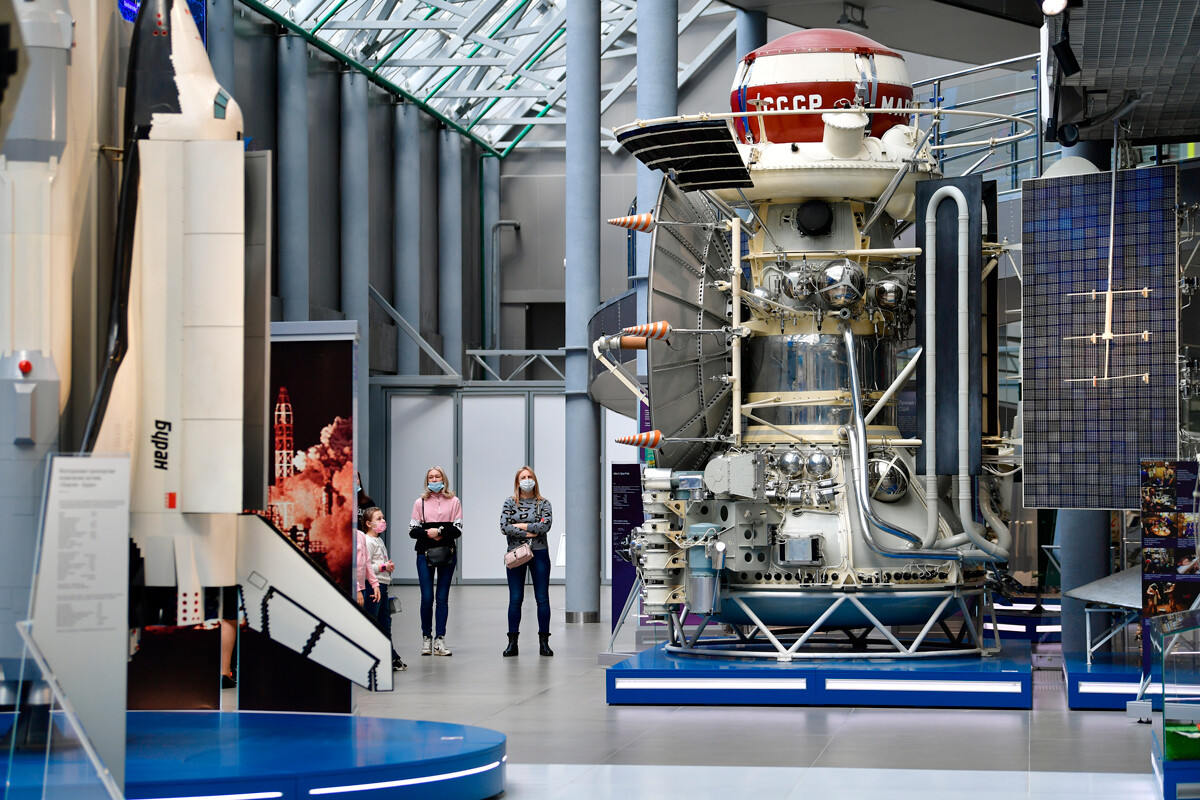

‘Mars 3’

SputnikMajor results were expected from ‘Mars 2’, but, once again, researchers were met with failure: the spacecraft should have landed on the surface of the planet but it crashed, entering its atmosphere at a wrong angle.

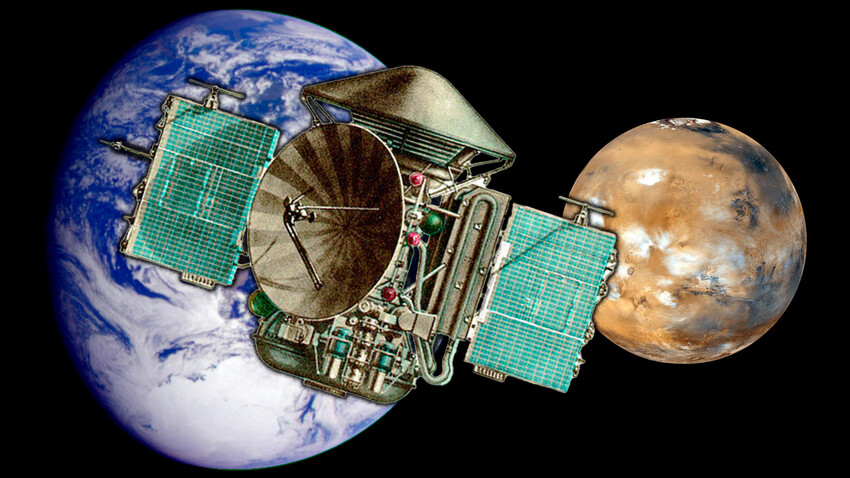

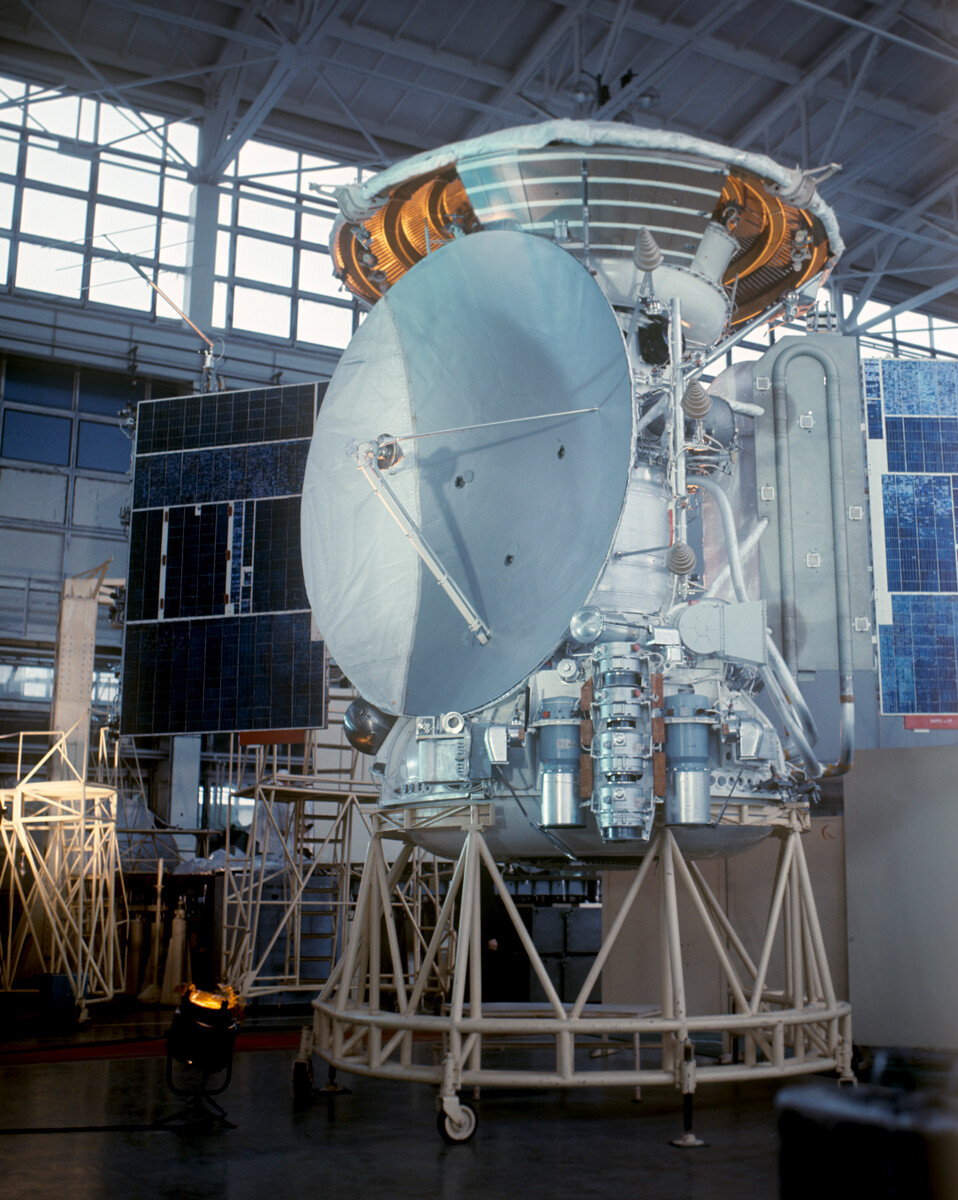

Even larger objectives were bestowed upon ‘Mars 3.’ This spacecraft was not simply an orbital satellite, but a whole complex of probes: two modules were meant to study the ‘red planet’ in tandem – one from its orbit, the other directly from the surface.

‘Mars 3’

Sputnik‘Mars 3’ took off from Earth on May 28, 1971. Unlike ‘Mars 1’ and ‘Mars 2’, the new spacecraft first circled the Moon to enter an interplanetary trajectory, then headed towards Mars. The acceleration gained from the gravitational forces of the Moon allowed it to reach Mars much faster than before – in just six months.

On November 8 already, ‘Mars 3’ approached the orbit of the ‘red planet’. However, at that moment it was impossible to land on its surface – the approach of Mars coincided with a severe dust storm and the weather conditions interfered with the research; however, Mission Control Center (TsUP) decided not to wait until the storm was over and to continue according to the initial plan.

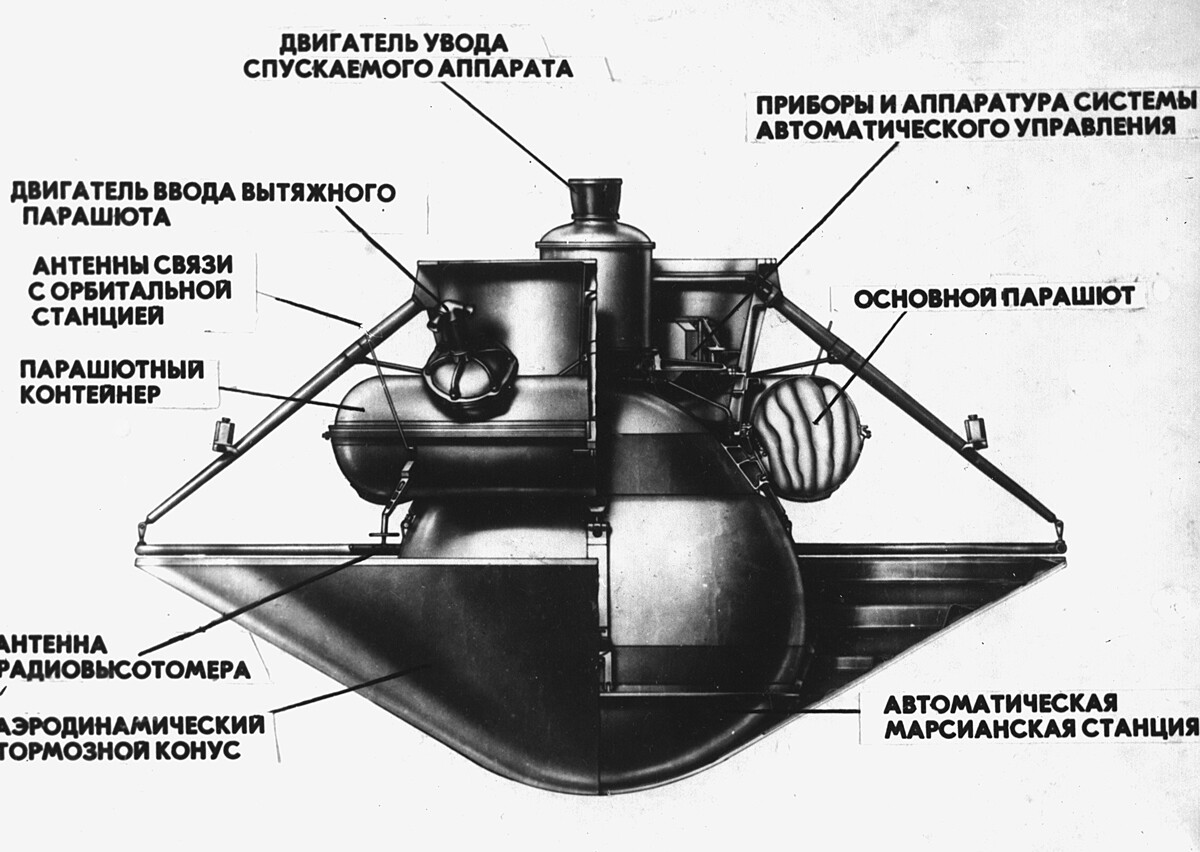

After yet another trajectory correction, the landing module separated from the orbital station and spent 4.5 hours heading towards Mars’ atmosphere.

“I still can’t remember it in any other way, but with a shudder,” Mikhail Marov, a direct participant of the mission, said.

The matter is, no one was fully certain in the correctness of all the calculations. Mars’ landscape, at the time, was poorly studied (that’s why the previous rover crashed) and the dust storm complicated things.

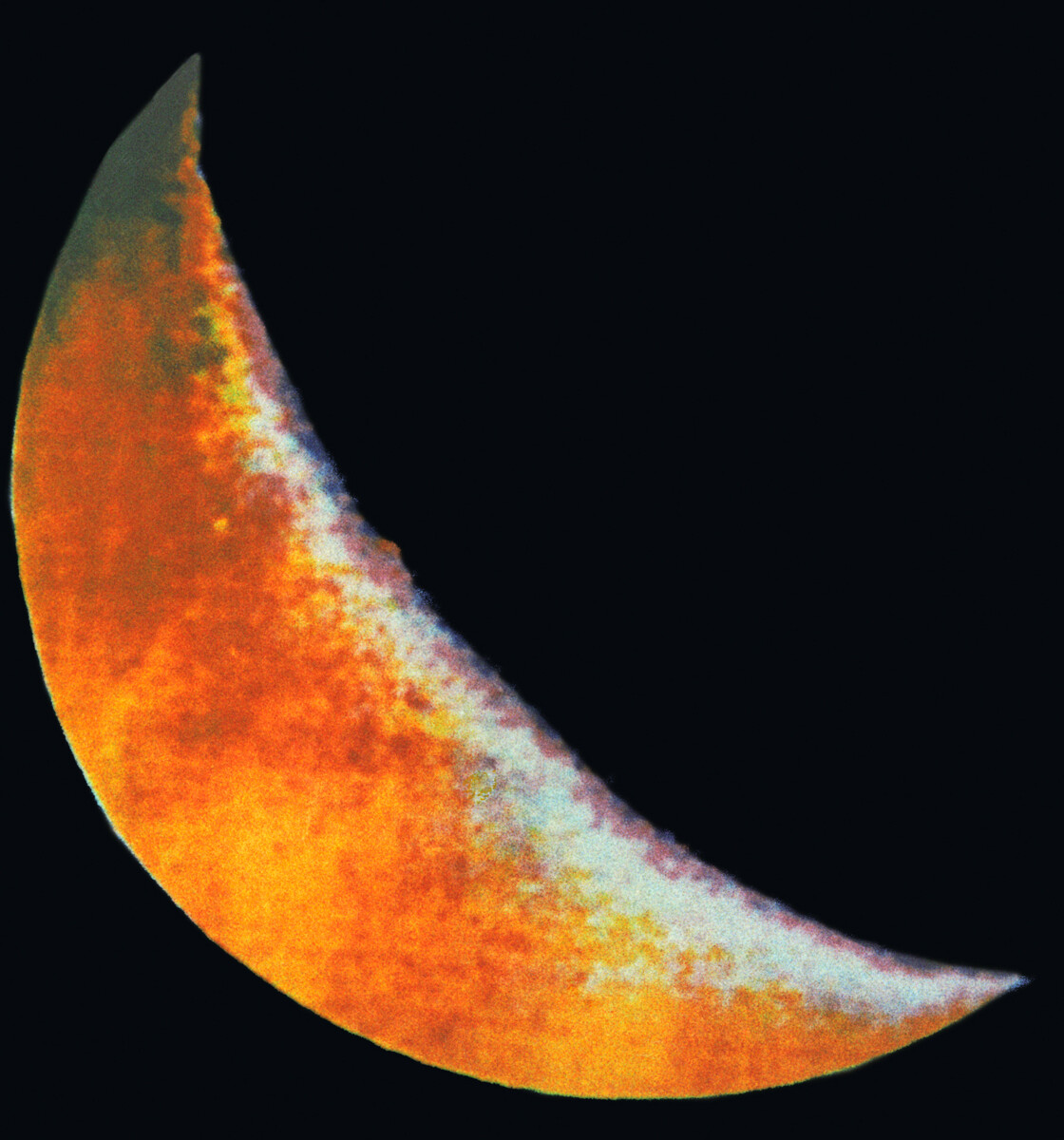

The first clear color image of the Mars

Sputnik“We saw that everything seemed to be going smoothly, without deviations or malfunctions, but most importantly – at the calculated point of time, we received a television signal, which could have come only after the module had landed and its antennas had opened. An incredible feeling of joy rushed over us all,” Marov remembered.

And suddenly, after almost 20 seconds, the signal abruptly cut off.

‘Mars 3’ managed to only send the first 79 rows of a photo-television signal to Earth. The picture consisted of chaotic stripes of white, black and gray, so no one even understood what the module had captured.

The reasons for the signal cutting off were never established. Different propositions were made: dangerous horizontal speed during landing, a voltage spike in the transmitter’s antennas, due to the dust storm or battery damage.

The orbital module of ‘Mars 3’ also had problems. After separating from the Mars rover, the satellite module entered an unplanned orbit – a flight altitude when the gravitational forces of the planet began to significantly impact the spacecraft’s trajectory, which made it impossible to predict its fate. The reasons for the station to behave in such a way were also never established.

But, despite this, the orbital module continued operating and sending data about Mars to Earth. For example, the measurements of the atmosphere composition, magnetic field and plasma.

The mission was officially completed in August 1972. The orbital station later burned up in Mars’ atmosphere, with the scientists also receiving a lot of valuable data from the planet’s orbit.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox