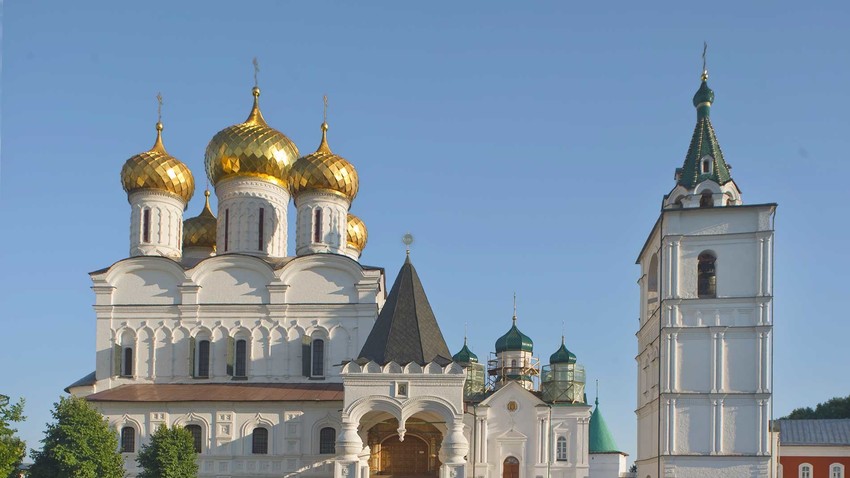

Kostroma. Trinity-Ipatiev Monastery. From left: Trinity Cathedral; Cathedral of Nativity of the Virgin; bell tower. North view. Aug. 13, 2017.

William BrumfieldAt the beginning of the 20th century, the Russian chemist and photographer Sergei Prokudin-Gorsky devised a complex process for vivid, detailed color photography. His vision of photography as a form of education and enlightenment was demonstrated with special clarity through his photographs of architectural monuments in the historic sites throughout the Russian heartland.

Logistical support for Prokudin-Gorsky’s work came from the Ministry of Transportation, which facilitated his photography along Russia’s rail and waterways, including the Volga River. One of the many historic towns Prokudin-Gorsky visited along the Volga was Kostroma, which rivals its neighbor Yaroslavl for the beauty of its churches and its importance in Russian history.

Trinity-Ipatiev Monastery. Trinity Cathedral, northwest corner with porch & stairs to west gallery. Summer 1910.

Sergei Prokudin-GorskyProkudin-Gorsky made two trips to Kostroma, in 1910 and again in 1911. He was particularly interested in the renowned Trinity-Ipatiev Monastery, which played a critical role in the history of the Romanov family in the early 17th century. Already acquainted with the imperial family, Prokudin-Gorsky was drawn to the monastery in advance of the tercentenary of the Romanov dynasty in 1913.

During the 16th century, the monastery’s main benefactors were Dmitry Godunov and his nephew - and future tsar - Boris Godunov (1552-1605). The

Trinity-Ipatiev Monastery. Trinity Cathedral, northwest corner with porch & stairs to west gallery. Aug. 13, 2017.

William BrumfieldAs a sign of favor, Ivan Kalita gave him extensive lands near Kostroma. According to legend, Zakhary/Chet was

Refuge for the Romanovs

After the death of Boris Godunov in 1605, Russia was consumed by a devastating period of social disorder, civil war and foreign intervention - particularly by Polish forces. In early 1613, the monastery gave refuge to the young Mikhail Romanov (1596-1645) and his mother, as marauding bands and Polish cavalry roamed the countryside. Despite the peril, Mikhail was crowned first tsar of the Romanov dynasty in July 1613.

Trinity-Ipatiev Monastery. Cathedral of Nativity of the Virgin; bell tower. North view. Summer 1910

Sergei Prokudin-GorskyAs stability returned to Russia under Romanov rule in the 17th century, the Ipatiev Monastery received substantial donations acknowledging its role in the dynasty’s accession. Central among the monastery’s buildings was the Cathedral of the Holy Trinity, rebuilt in 1650-52.

As usual during the early medieval period, the original monastery structures, including the main church (sobor), were made of wood. In the mid-16th century Dmitry Godunov built the first masonry version of the cathedral, which was severely damaged in 1649 from an explosion of gunpowder stored in the cellar. Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich Romanov, Mikhail’s son, assented to a rebuilding in 1650.

Trinity-Ipatiev Monastery. From left: Trinity Cathedral, west gallery; Cathedral of Nativity of the Virgin; bell tower. North view. Aug. 13, 2017.

William BrumfieldThe design of the cathedral is traditional, with a crown of five cupolas. Yet its form is unusual because it has its main façade on the north, with an ornately decorated porch at the northwest corner containing a stone staircase that ascends to an enclosed gallery. Within the gallery, the main portal is on the west, as usual in Russian Orthodox practice.

Although the original glass negative of Prokudin-Gorsky’s image is missing in the Library of Congress collection, his contact prints show that he photographed the northwest porch and staircase, which were later used by Nicholas II during his 1913 visit. A comparison with my photograph of August 2017 shows the excellent state of preservation of these elements.

After completion of construction in 1652, work commenced on a large icon screen. Two years later, in 1654, master artists from Kostroma began the interior frescoes, but work came to a halt in 1656 due to an outbreak of plague that decimated the town. The interior was finally painted in the summer of 1685 by a distinguished group of court artists that included Gury Nikitin and Sila Savin.

Trinity-Ipatiev Monastery. Cathedral bell tower from north entrance arch. Summer 1910.

Sergei Prokudin-GorskyA cathedral’s destruction and resurrection

Another of my photographs shows the entire cathedral complex from the north, including the 17th-century bell tower and, in the distant center, the Cathedral of the Nativity of the Virgin, rebuilt in 1860-64 by Konstantin Ton in the Russo-Byzantine style at the southwest corner of the Trinity Cathedral gallery. The new Nativity Cathedral was commissioned by Alexander II in commemoration of the 250th anniversary of the founding of the Romanov dynasty.

The Nativity Cathedral has had a turbulent history. After the closure of the monastery in 1922, after the Bolsheviks came to power, its buildings were converted to other uses. In 1932, the Nativity Cathedral was demolished.

Trinity-Ipatiev Monastery. Cathedral bell tower, northeast view. Aug. 13, 2017.

William BrumfieldIn 2008 a decision was taken at the highest state level to rebuild the Nativity Cathedral in Konstantin Ton’s Russo-Byzantine design. The basic structural work was completed by 2013 to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the reestablishment of Russian statehood in 1613. Work on the interior continues.

Prokudin-Gorsky took a closer view of the north façade of the Nativity Cathedral, as did I with a wider lens that shows the west gallery on the left. On the right side of both our photographs is the main bell tower, whose basic open-gable form was begun in 1603 by the boyar Dmitry Godunov, uncle of Tsar Boris Godunov. Expanded during the subsequent half century, the archaic structure gained a decorative tower in the 19th century.

Trinity-Ipatiev Monastery. Cathedral bell tower, upper tier, east view. Aug. 13, 2017.

William BrumfieldProkudin-Gorsky took yet another view of the bell tower from the monastery’s north entrance arch. Both his views show the walls of the bell tower covered with paintings of scenes from the life of Christ. During the Soviet period, these paintings were effaced. At the time, they were considered 19th-century additions in a Western academic style that promoted Christianity and disfigured the earlier form. My photographs show the tower as a white monolithic structure with an impressive display of light and shadow.

In January 1991, the divine liturgy was once again celebrated in the Trinity Cathedral, and over the next three years agreements were concluded that allowed joint use of the monastery as a state museum and a functioning monastic institution. At the end of 2004 the entire monastery was granted to the Kostroma Diocese.

Trinity-Ipatiev Monastery. From left: Cathedral of Nativity of the Virgin; Trinity Cathedral; bell tower. East view across Kostroma River. Aug. 13, 2017.

William BrumfieldIn the early 20th century the Russian photographer Sergei Prokudin-Gorsky devised a complex process for color photography. Between 1903 and 1916 he traveled through the Russian Empire and took over 2,000 photographs with the process, which involved three exposures on a glass plate. In August 1918, he left Russia and ultimately resettled in France with a large part of his collection of glass negatives. After his death in Paris in 1944, his heirs sold the collection to the Library of Congress. In the early 21st century the Library digitized the Prokudin-Gorsky Collection and made it freely available to the global public. A number of Russian websites now have versions of the collection. In 1986 the architectural historian and photographer William Brumfield organized the first exhibit of Prokudin-Gorsky photographs at the Library of Congress. Over a period of work in Russia beginning in 1970, Brumfield has photographed most of the sites visited by Prokudin-Gorsky. This series of articles will juxtapose Prokudin-Gorsky’s views of architectural monuments with photographs taken by Brumfield decades later.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox