How to get there from Moscow:

by train from Yaroslavl Station (travel time - 1:15-1:40 hrs)

When NOT to go:

During major Orthodox holidays: Christmas (January 7) and Easter, as it's getting overcrowded

This small town has such a rich history and so much to tell about Russian culture and traditions that anyone interested in the country should definitely pay a visit. What’s more, the city is part of the Golden Ring tourist route, the only one inside Moscow Region, making it relatively reachable for a day trip from the capital.

A posad in Ancient Rus was the territory that surrounded a monastery or princely domain. They tended to be inhabited by artisans and traders, so were basically markets. Such a settlement took shape around the Trinity-Sergius Monastery by decree of Catherine the Great in 1782, and was named Sergiev in honor of St Sergius of Radonezh.

According to legend, Sergius of Radonezh arrived here in the 1340s (some historians even pinpoint the year as 1342). He and a group of monks built a small dwelling for themselves, next to which they constructed a church in honor of the Holy Trinity.

The Trinity Cathedral

Legion MediaBe sure to visit Trinity Cathedral. The modern version was built in 1422 (although it has been modified and renovated several times since). The finest master craftsmen of the 15th century worked on the interior decoration. It was for the iconostasis here that Andrei Rublev painted his famous Trinity icon, one of the most revered in the Russian Orthodox Church. It takes a trained eye to spot it. Look in the bottom row of the iconostasis – the first icon to the right of the gate leading to the altar.

Here’s a handy church-going hack. If you don’t know the name of a church, look at the lower icon to the right of the gate – a church is always devoted to this icon.

Iconostasis of the Trinity Cathedral

Getty ImagesTrinity Cathedral was a particular favorite of Ivan the Terrible. It was here that he was baptized, got married, and held prayers after successful military campaigns.

The monastery withstood a siege by Polish invaders during the Time of Troubles, and supported Peter the Great when he was plotting a coup d’état against the regency of his half-sister Sophia Alekseyevna.

There are about ten churches inside the monastery, built at different times from the 15th to the 18th century. They offer a fascinating glimpse into the evolution of Russian church architecture.

There’s no need to see inside all of them, otherwise you’ll suffer church overload. But Assumption Cathedral, commissioned by Ivan the Terrible himself, is a must. It is recognizable by its blue domes with golden stars (by the way, whatever Golden Ring city you happen to be in, such domes signify that the shrine is dedicated to the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary).

The Assumption Cathedral

Legion MediaInside, you should definitely look up to admire the murals. Also, be sure to find the old wooden coffin of St. Sergius of Radonezh (although his actual relics are in Trinity Cathedral).

For Russians, the name of Sergius of Radonezh is associated with the country’s revival after the centuries of Tatar-Mongol rule, and the so-called Russian Renaissance. He and his students founded not only the Trinity-Sergius Lavra, but a dozen other monasteries in central Russia, making him perhaps the most revered Russian saint in the Orthodox world. In the 20th century, he was also officially recognized by the Catholic Church.

His secular name was Bartholomew. According to legend, it was his childhood dream to become a monk, and after taking the vows he became Sergius. He was born near the city of Rostov in Yaroslavl Region (another Golden Ring city), but later his family moved to Radonezh.

Mikhail Nesterov. The Vision to the Youth Batholomew

Tretyakov GalleryHis unworldly spiritual path, asceticism, and moral sermons profoundly affected his descendants, who elevated him to the sainthood, and to a special rank at that –Prepodobny, meaning “venerable.”

Sergius of Radonezh essentially reformed the whole of monastic life. He forbade monks from leaving the monastery grounds to beg for alms, whereupon they began to farm and provide for themselves. In addition, he introduced the principles of communal living, which meant no private property at all, common bread, etc., which enabled Russian monasteries to become hospices, i.e. they were able to receive wanderers and pilgrims, which figuratively and literally helped to “bind the lands and the people” – a vitally important concept at that time.

The spiritual authority of Sergius was so immense that he is considered nothing less than the “unifier of Rus” – it was he who rallied the fragmented feudal principalities to unite around just one, Muscovy, in order to cast off the Tatar-Mongol yoke. For many decades, the Golden Horde had been ravaging the Russian lands (the reason Sergius and his parents moved to Radonezh was because Rostov had been sacked).

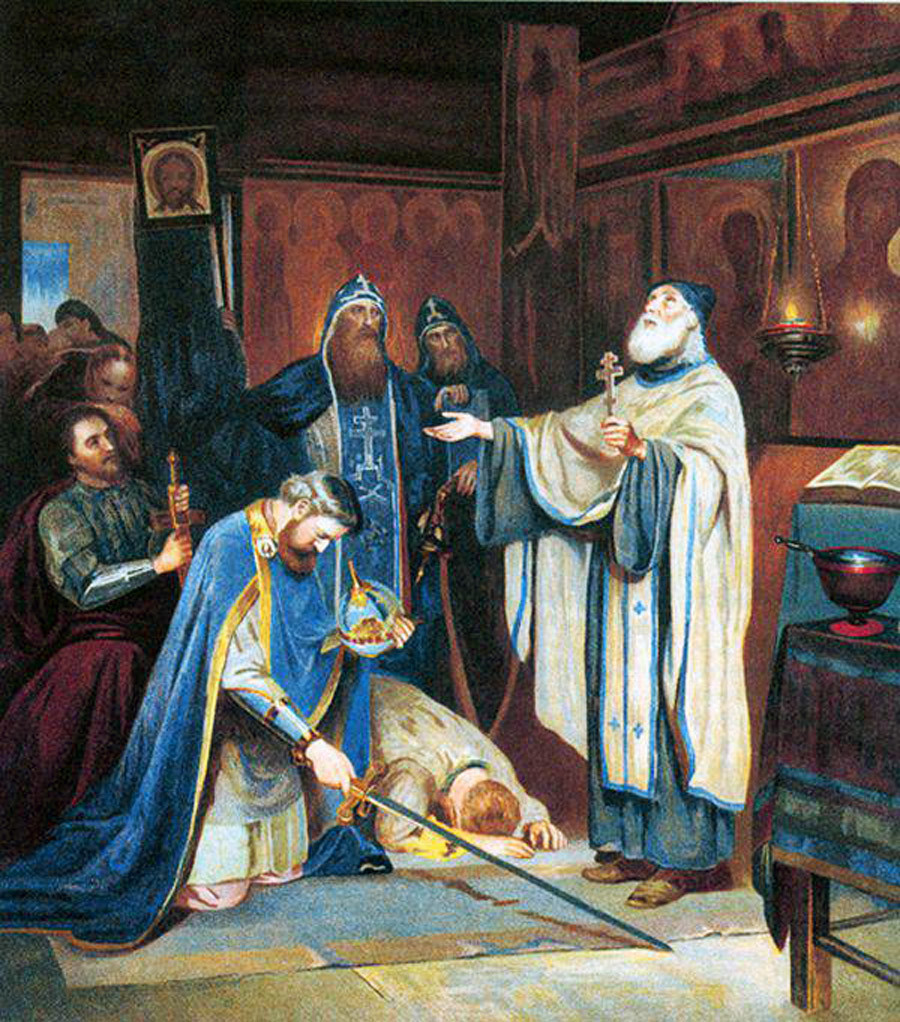

Alexander Novoskoltsev: Sergius of Radonezh blessing Dmitry Donskoy

Public domainBefore one of the most famous battles in medieval Russia – the Battle of Kulikovo Field – Prince Dmitry Donskoy requested the blessing of Sergius, who duly complied and even sent two of his bogatyr (warrior) monks to fight against the Tatars.

The monastery is not the be-all and see-all of the city. There are a dozen cozy museums to visit. The main one, the Sergiev Posad State Historical and Art Museum Reserve, houses a large collection of ancient icons and church handicraft items, as well as other exhibits telling about Russian life from ancient to Soviet times.

Bely (White) Pond not far from the Lavra

Legion MediaThere is also the Toy Museum, founded in 1918, where you can see old Russian and Soviet toys, including ones that belonged to the children of the last Russian tsar, Nicholas II.

And to see how a typical Russian hut looked, you can visit the Once-Upon-a-Time Museum, in which kitchen utensils, spinning wheels, and all kinds of tools are displayed – everything that Russian hut dwellers would have owned.

Sergiev Posad

Legion Media

Not far from the Lavra are three other places worth a trip.

1. Abramtsevo Estate (see our in-depth article here).

Built by millionaire merchant Savva Mamontov, it hosted gatherings of the finest Russian writers and artists of the late 19th–early 20th century. It could be said to be a prototype of modern art residences.

Abramtsevo Estate

Konstantin Kokoshkin/Global Look Press2. The Pokrovsky Khotkov Monastery

The Pokrovsky Khotkov Monastery was the first refuge of the young monk Sergius of Radonezh. It was from here that he set off to found his dwelling place. The main Intercession Cathedral stores the relics of his parents. There is also the red-brick Nikolsky Cathedral, built much later in 1904, but in the style of a Byzantine temple.

3. Muranovo Estate

If you’re interested in how the estate of a second-tier nobleman looked in the 19th century, then head for Muranovo. Here, you will see a manor house and park – some of the trees are more than 150 years old! In addition, you’ll learn about the Russian poet Fedor Tyutchev, whose family lived here. (Watch more photos of the estate here)

Muranovo

Vadim RazumovIf using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox