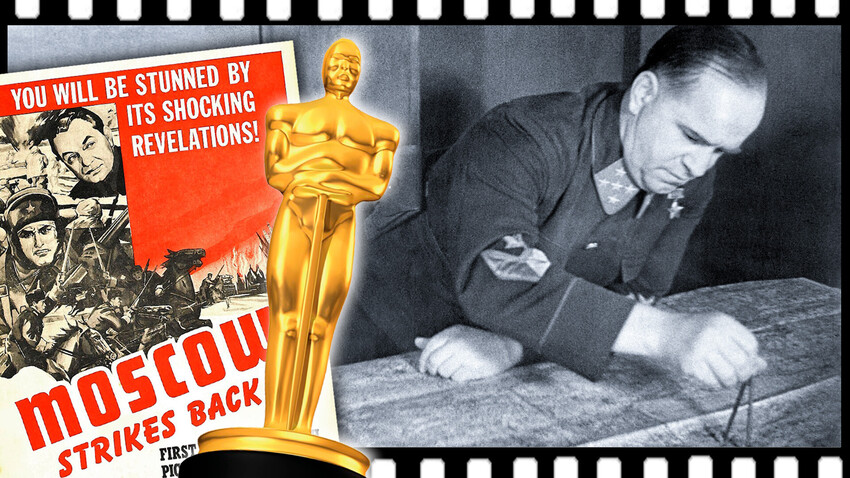

That Oscar ceremony was the first to be held in the midst of a world war, by which point, the U.S. had already been actively participating. The setting was 1943, at the ‘Coconut Grove’ nightclub of the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. Nobody was wearing tuxedos or evening dresses or expensive jewelry and diamonds - everything was quite informal, with many actors even wearing military uniforms. The famous Oscar statues were made of plaster. Almost all of the nominated movies had to do with war, with a record 25 movies vying for victory in the Best Documentary category. Four ended up splitting the prize. Among them was ‘Moscow Strikes Back’.

“This presentation did not take long, rather it was an introduction to the issuance of the main prizes. But it was truly historic, because it was the first Oscar that Russia won,” records allegedly recall actor Tom O’Neill, a participant in that 15th ceremony, as saying.

In reality, according to historians, the movie had nothing to do with the defense of Moscow and had zero chances of winning an Oscar. The reason it did was entirely down to politics.

After Germany carried out its first air raids on the Soviet Union, Wehrmacht forces had hoped to quickly capture the European part of the country. And, although a rapid and decisive victory was out of the question, they progressed quickly toward the Soviet capital.

Shot from the ‘Moscow Strikes Back’

“On the night of July 23, 1941, Hitler’s forces carried out their first air raid on Moscow. The capital awaiting an armada of planes - 220 bombers,” frontline cameraman Mikhail Poselsky recalled. “We caught a terrifying sight on the Arbat. A bomb, weighing half a ton, smashed through the roof of the Vakhtangov Theater and exploded inside the auditorium. There were five staff on duty that evening and all were killed. In the morning, I filmed my first war footage - the traces of the first bombing of the capital.

A month on from those events, Moscow was under fire. According to historians, in four months of war, by October, Soviet losses amounted to a million people. The Germans were so certain of Moscow’s fall that they approached the capital in dress uniforms, stopping just 100 kilometers outside. Panic gripped the Soviet nation. Moscow was preparing to surrender. By mid-October, as it would later become known from classified documents, almost 800 government staff fled to save themselves.

Shot from the ‘Moscow Strikes Back’

SputnikThe panic ground to a halt with Joseph Stalin’s decision to stay in Moscow and prepare to mount a defense. And, in order to announce it to the world, the Soviets decided to hold their regular anniversary parade commemorating the victory in the October Revolution. The risky decision was deemed necessary for raising the nation’s spirits. Footage of the November 7 parade - from where the marching soldiers then went straight to war - made it into the film.

A couple of days after the parade, Stalin held an emergency meeting with the head of the cinematography department, Ivan Bolshakov: “Our army is about to switch to an offensive outside Moscow. We plan to deliver a blow of incredible might to the Germans. I think they will not withstand it and roll on back… We need to shoot all that and make a quality movie,” Bolshakov later quoted Stalin. The Soviet leader practically ended up being the director.

There weren’t that many cinematographers left in Moscow at the time: the main documentary-making studio had already been taken 1,000 km out of Moscow. Only a small crew remained to document Moscow’s defense.

Shot from the ‘Moscow Strikes Back’

SputnikShooting began immediately on a very rough plan, but with a strict objective - to show the might of the Soviet Army and destroy the myth of the indesuctible Nazis.

Work went on in tough conditions. Freezing weather struck. Cameraman Teodor Bunimovich recalled: “Before every session, I had to lie in the snow, warming the camera under a sheepskin coat. Reloading was a huge chore. My frozen hands refused to move properly.”

The fighting that took place on a territory of more than 1,000 kilometers was shot by a crew of 30 men and everyone had to spread out in such a manner as to not miss out on any valuable footage.

Shot from the ‘Moscow Strikes Back’

Sputnik“Late at night, coming back to the studio, they came back with thousands of meters of priceless shots, prepared their gear and film for the following day, looked over the materials shot during the previous sessions and, catching about an hour’s worth of sleep, set out for the front line again,” co-director Ilya Kopalin remembered. Every once in a while, a car would come back, carrying the body of a colleague, together with his broken gear.

Work carried on day and night on a tight schedule, with cameramen cooped up in cold rooms, cutting film. They never saw the inside of a bomb shelter, even during air raid sirens. In late December 1941, a month and a half later, the work was complete and it was time to lay down the sound.

Shot from the ‘Moscow Strikes Back’

Sputnik“The most exciting and responsible stage of recording had begun: Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony. A joyful Russian melody, a raging protest, with its weeping chords. The picture, meanwhile, showed a city burning, gallows, dead bodies and footage of violence and barbaric acts amid the fascist retreat. We listened to the music, watched the screen and cried. The musicians cried as well, as they carried on playing with frozen hands,” Kopalin recalled.

‘Moscow Strikes Back’ was released in Soviet cinemas on February 18, 1942. Eight hundred copies were made and sent out across the country on the same day to show in various other auditoriums, including army regiments; a portion of that was sent to the United States, Britain, Iran and Turkey. That same year, the movie was awarded a prize by America’s National Society of Film Critics, followed by an Oscar in 1943, where it was accompanied by the description: “For its vivid presentation of the heroism of the Russian Army and of the Russian people in the defense of Moscow and for its achievement in so doing under conditions of extreme difficulty and danger.”

Shot from the ‘Moscow Strikes Back’

SputnikHowever, the Academy Award wasn’t simply an acknowledgement of the Soviet cinematographers’ brilliance - it was also politically motivated, according to film historian Sergey Kapterev. “Both Britain and the U.S. had to convince their tax payers of the necessity to assist the Soviet Union in light of the March 1941 Lend-Lease legislation, to convince them that the USSR was now a victim of Hitler’s aggression and an important ally,” Kapterev says.

Shot from the ‘Moscow Strikes Back’

SputnikThe USSR being positioned as a “communist menace” at the time did not help. Everyone remembered that, early in the war, the Soviets had nearly been allies of Hitler’s Germany and even struck a non-aggression pact with him (the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact). Then, after Hilter attacked Poland, came the signing of another treaty, which presupposed the division of Poland between Germany and the USSR. In a word, the movie was intended to restore the face of the USSR in Western eyes during the formation of the anti-Hitler coalition. In order to ensure its success in the States, it had to be adapted to the American viewer.

The American version was more dynamic, as well as being 14 minutes shorter than the original, with some of the ideological bits, intended for the Soviet viewer, cut out. The documentary was recut and the narration completely changed, with journalist Elliot Paul and writer and Communist party member Paul Maltz brought in to revise it. The voiceover was one by Edward G. Robinson, famous for playing bloodthirsty gangsters, but also his reputation of a consummate professional with experience in serious political and military projects. Robinson’s face even ended up gracing the posters for the documentary. And so, ‘Moscow Strikes Back’ - the American cut - was made presentable and eligible for an Oscar.

The motion picture enjoyed colossal success, viewed by some 16 million Americans and Brits. The New York Times wrote: “Here is a film to knot the fist and seize the heart with anger, a film that stings like a slap in the face of complacence.”

For many, those proved to be the most shocking images: never before had a documentary contained scenes of torure and death.

Only days after the U.S. premiere in August 1942, a second Lend-Lease protocol was signed. And although the Oscar was awarded to the film in 1943, the statue played a major role in impressing upon the Allies the need for uniting with the Soviets against Germany.

According to Valery Fomin, it was this movie that introduced the practice of filmmakers documenting war crimes, including ones that would go on to be presented as evidence at the Nuremberg Trials. Two hundred and fifty two cameramen filmed the violence over the space of 1,418 days. One in five either lost their lives, with every second receiving wounds or contusions.

Even so, the fact of the Oscar win was kept hushed in Soviet history for several decades; meanwhile, in the U.S., those who participated in the adaptation were charged with collaboration with an enemy state. Such was the reality of the Cold War.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox