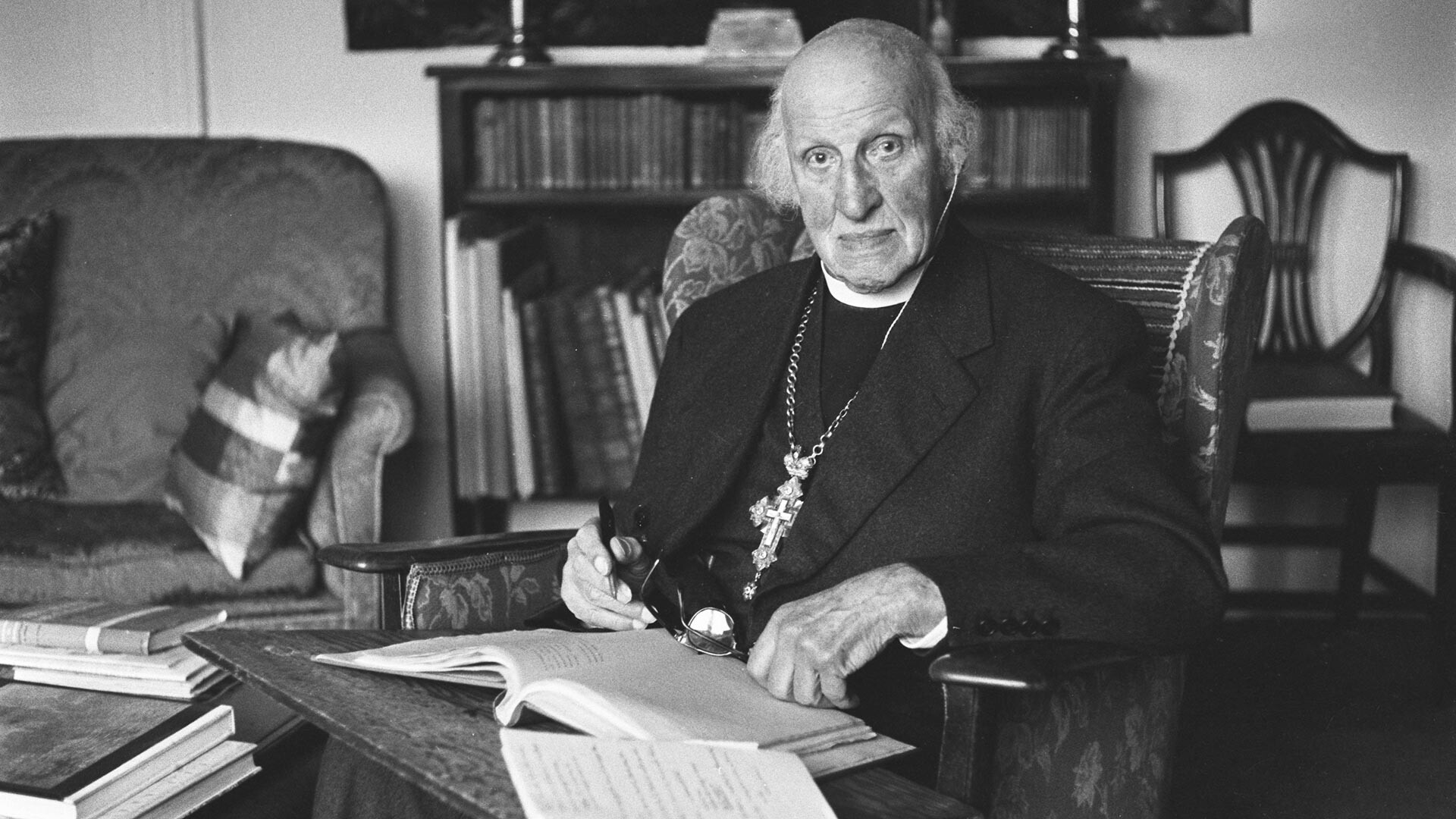

Dr Hewlett Johnson in 1966.

Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesThe relationship between the atheistic Soviet state and the Orthodox - as well as the Catholic and Protestant - churches, were always complicated, to put it mildly. They ranged from the destruction of places of worship and repressions against priests to attempts to reach a consensus and some workable solution of coexistence. However, even during the period of relative calm, strict state oversight of religion did not falter even for an instant.

Meanwhile, some spiritual leaders managed to become genuine friends of the Soviet Union. What’s more, these were priests from Western capitalist countries.

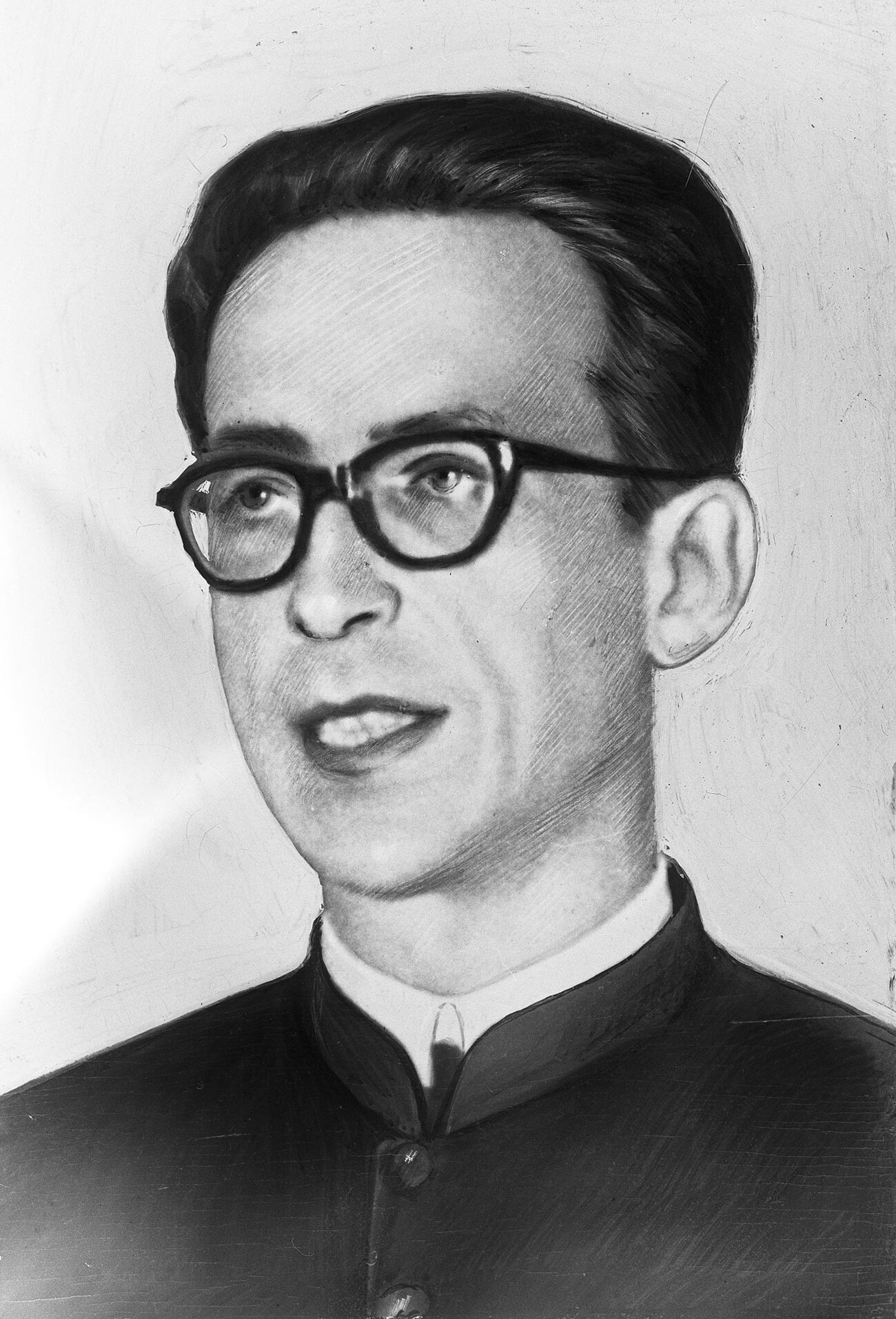

Andrea Gaggero.

SputnikAs pacifists and proponents of leftist worldviews, Italian priest Andrea Gaggero and Canadian protestant missionary James Endicott actively fought against nuclear weapons proliferation and the escalation of the Cold War. Both were awarded the Lenin and Stalin awards, respectively, “For Strengthening Peace Among Peoples”.

However, none of the Western faith leaders had been a more welcome guest in Moscow than the dean of the most major Anglican institution in all of Britain - the Canterbury Cathedral. His name was Hewlett Johnson.

“The Red Dean of Canterbury”, as they referred to Johnson in Britain for his love of the Soviet Union, took up the post of abbot in 1931. He was 57 years old. Famous for his sympathies toward communist ideas as a member of the Labour Party, he became a real thorn in the side of the conservative clergy, particularly for the Archbishop of Canterbury Cosmo Gordon Lang.

Reverend Dr Hewlett Johnson and his secretary surveying the destroyed Cathedral Library, June 1942.

Fox Photos/Hulton Archive/Getty Images“Hewlett Johnson’s post was for life and firing him was impossible”, Soviet diplomat Ivan Maisky, who became the socialist priest’s friend, remembered. “At the same time, the abbot was very determined; he was not peaceful with the Archbishop around and energetically rejected every intrigue and machination that the Church authorities used to poison his existence.”

“He immediately left a strong impression on me,” Mayskiy wrote. “Tall, slim, somehow really light on his feet, despite his age, with a smart, spiritualized face, always clad in the priest’s black cloth, Hewlett Johnson seemed like a rather extraordinary man. And he didn’t just seem - he indeed was… His entire stature evoked a sense of something elevated and noble.”

In the mid-1930s, the priest performed several trips to the Soviet Union, resulting in his 1939 book ‘Socialism On the Sixth Continent’, where he diligently described the economic and societal transformations in the country. It was translated into 24 languages, achieving major popularity.

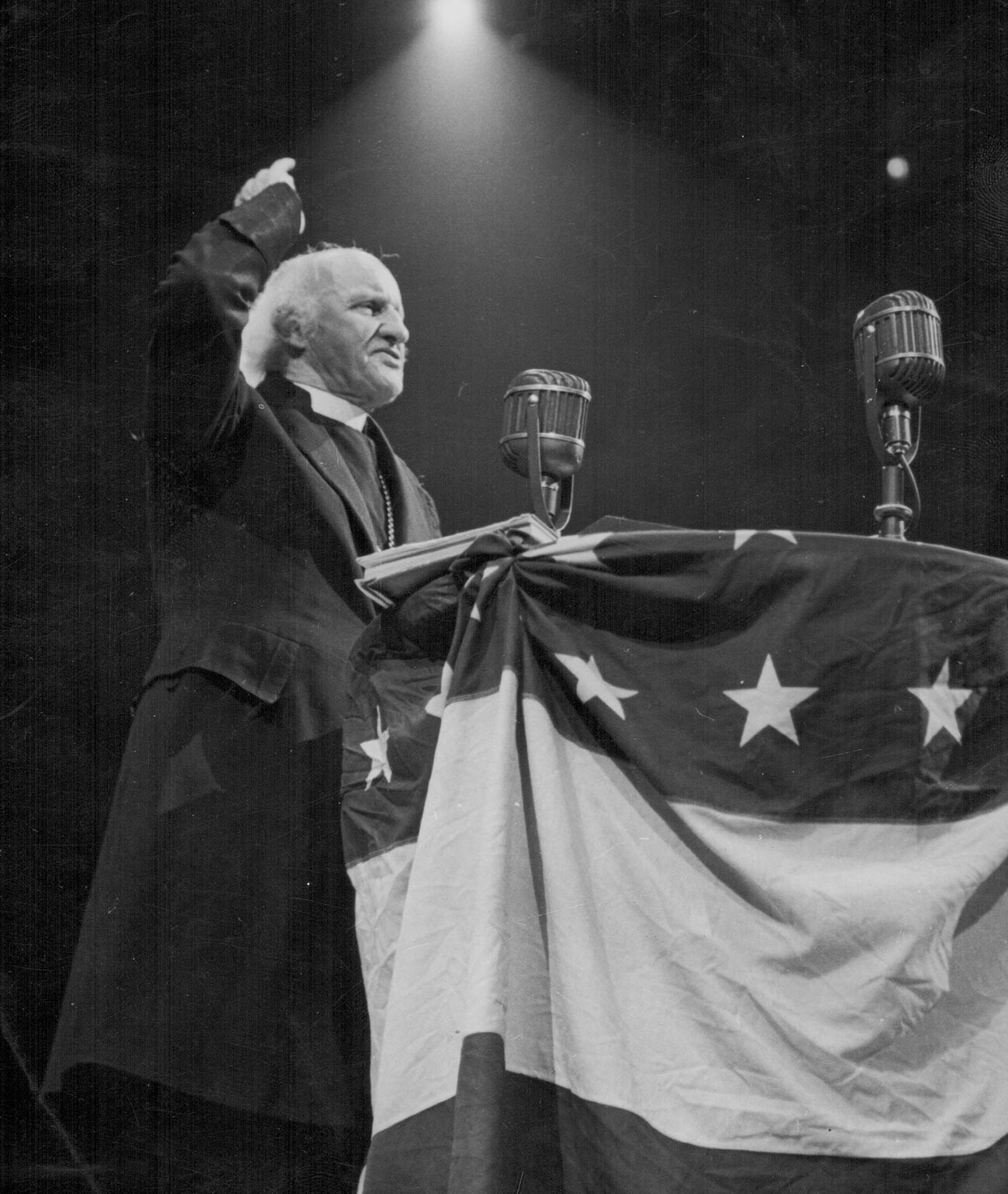

Reverend Dr Hewlett Johnson, 1948.

Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images“The faith of Communism has gripped the world as no other movement since the rise of Christianity…” he said. “I am convinced that a synthesis of the two faiths is possible and will eventually bring blessings to the entire human race <…> Is [Communism] Christian? I say ‘yes’, as I did 50 years ago. Russia <…> has, in spite of all her faults, founded her economy on a Christian theory.”

“A true Christan cannot be an enemy to communism,” the Red Dean told Maisky. “On the contrary, there are many points of convergence between Christianity and communism.” Johnson, however, never became a member of Britain’s communist party.

During World War II, aside from caring for the refugees and his Cathedral, which suffered during the bombings, Johnson actively participated in the collection of donations to aid the Soviet Union.

Dean of Canterbury Hewlett Johnson with his family in the Lesnyye polyany ("Forest clearings") summer camp in Moscow region, 1956.

Vasily Malyshev/SputnikIn 1945, the abbot was officially invited to Moscow to celebrate Victory Day, where he received a warm welcome. Patriarch Alexy I of Moscow even gave him an Orthodox cross, which Johnson never parted with. The new Archbishop of Canterbury, Geoffrey Francis Fisher, kept asking Johnson to refrain at least from wearing it to official functions - all to no avail.

Johnson had been a source of frustration for British society for years, due to his support of the Soviet Union in practically every area, including the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and the 1939-1940 Winter War against Finland. The controversial sides of Soviet society - such as the mass repressions and purges - were by and large ignored by the Red Dean.

In July, 1945, the priest was awarded the Order of the Red Banner of Labor, then, in 1951, the International Stalin Prize, “For Strengthening Peace Among Peoples”, which further added to his list of enemies back home. Johnson was sarcastically recommended to go on a lengthy missionary trip to the salt mines of Siberia. He also received the following anonymous message: “Traitor. Resign. You defile the very stones of Canterbury <…> England is too good for a Bolshevik.”

Nowell Johnson presents the medal of the Stalin Peace Prize laureate to her husband, Dean of Canterbury Hewlett Johnson.

Vasily Egorov, Vladimir Savostyanov/ TASSThanks to his prestigious status, Johnson remained invulnerable to his attackers. Winston Churchill was issuing calls to ignore the priest, in order to take the spotlight away from his activities. Nevertheless, intelligence services had unofficially carried on keeping a close eye on him.

The Red Dean stayed loyal to Stalin’s USSR to the end. In 1956, he refused to acknowledge Nikita Khruschev’s initiative to dismantle the personality cult around “the father of nations”.

In 1963, aged 89, and having never succumbed to the pressure of his opponents, Hewlett Johnson voluntarily vacated the post of abbot at the Canterbury Cathedral. He passed away three years later. Despite all the scandal surrounding his persona, he was buried next to the cathedral, which he dedicated so many years of his life to.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox