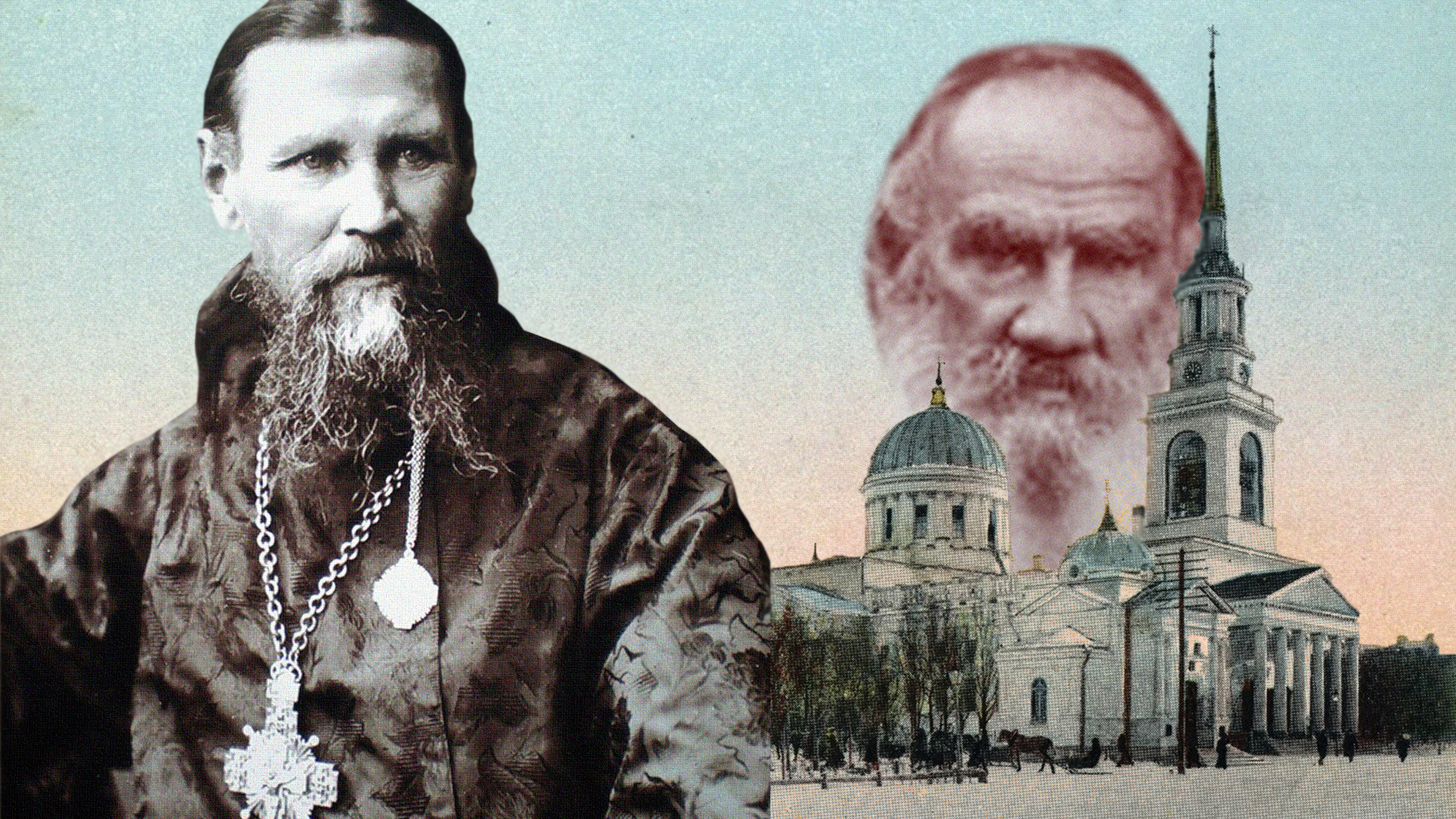

These days it is difficult to imagine how at the turn of the 20th century a simple priest could attract pop-star crowds. Such magnetism was usually possessed only by members of the tsarist family. But John of Kronstadt was considered a saint even in his own lifetime, famed for his supposed ability to heal the sick through prayer. The richest people in the Russian Empire donated vast sums to him, which he distributed in full to the faithful, living very modestly himself.

In 1990, John was canonized as a saint in Russia. To commemorate the 30th anniversary of this event, four monuments of him were created by Rostov sculptor Konstantin Chernyavsky and were gifted by Russian charity funds to Orthodox communities around the world: in Hollywood, Melbourne, Abkhazia and in John's native village Sura in Arkhangelsk Region, Russia. In 2019, monuments to John of Kronstadt were also unveiled in Hamburg, Washington D.C. and the Russian city of Voronezh.

So who was the man behind the myth?

John was born in 1829 in the Arkhangelsk region into a very poor family. He studied at a local theological seminary, later winning a scholarship to the St Petersburg Theological Academy. His academic ability aside, he was an unremarkable young man who made no indelible impression on fellow students. He liked to walk alone and pray a lot.

In 1855, John went to serve at St. Andrew's Cathedral in Kronstadt, securing a clergy position by marrying the daughter of the local archpriest. And although Orthodox priests usually had large families, after their wedding John informed his wife that they would live like brother and sister in the name of spiritual service.

St. Andrew's Cathedral in Kronstadt (was destroyed in Soviet times)

Public domainJohn began his ministry immediately on receiving the parish of Kronstadt, a severely disadvantaged region not far from Petersburg. Back then it was a port city, where poverty, vice and depravity were endemic. Every day he served the liturgy in the local church, after which he handed out alms.

Then he went round the houses and shacks, where sick, poor women with children huddled together while their husbands worked, drank or went looting. He sat with the children, talked to the women, and gave them everything that he had. The locals observed the eccentric scene of John returning home barefoot with arms crossed in prayer, having given his boots and cassock to the needy.

In 1859, John made his first diary entry about the healing — or even resurrection — of a baby. He held the tiny, already cold body in his arms, praying and performing the sacrament of baptism. Suddenly, the infant came back to life. In the 1860s, John recorded several cases of how he healed the sick, writing that he “begged for the afflicted to be healed, and the Lord delivered His mercy.” This was repeated more than once, and on occasions he healed whole groups of people.

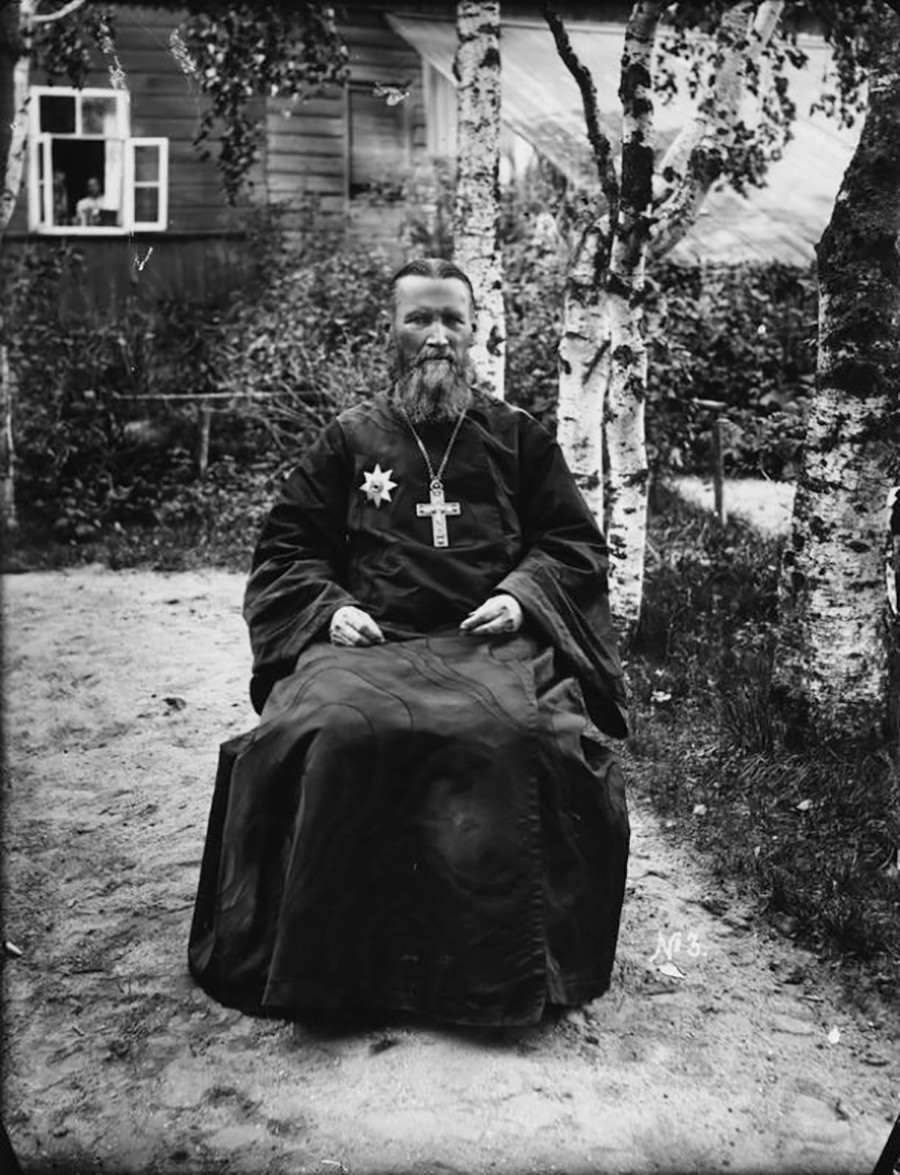

John of Kronstadt with one of his godsons

Central State Archive of Film, Photo, and Sound Documents of St. PetersburgSoon the press got wind of it. In 1883, an article appeared in which 16 people claimed that John had healed them. From that moment on, his fame began to spread nationwide. A not-insignificant role in the priest's growing popularity was played by the “pious woman” Paraskeva Krapivina, who appeared before John. She became a kind of “earthly affairs” adviser, and strongly believed that John’s destiny lay beyond his modest Kronstadt parish. Today, we might describe her as his PR manager.

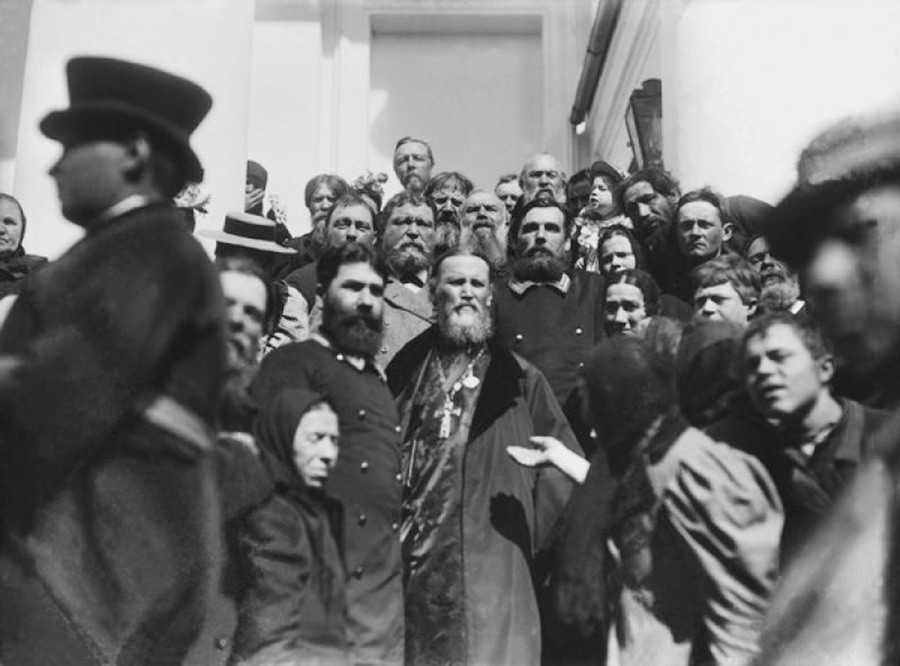

John of Kronstadt in Petersburg city hall

Central State Archive of Film, Photo, and Sound Documents of St. PetersburgIn particular, she organized the collection of funds from benefactors and people grateful for John’s miracles. Later, the richest people in Russia started donating huge sums of money. John himself began to hand out even more to the sick and suffering — for example, he gave one sick woman a whole thousand rubles (when the monthly salary of a factory worker was 30 rubles). In addition, he could readily donate 50,000 rubles to the construction of a charitable institution, such as a shelter, school or hospital. Rich gifts and huge donations also came from the tsarist family.

In the 1880s, John’s miraculous healings and highly passionate sermons made him known a household name in Russia. At Krapivina’s suggestion, he began to go on "tours" of the country, meeting believers and saying mass in local churches and monasteries. Thousands of believers flocked to touch or at least lay eyes on the great preacher. At railway stations, he was greeted by crowds of people who would not let him through. Although his stays were short, everywhere he went he tried to heal or at least comfort and bless as many people as possible.

John of Kronstadt and his parish

Central State Archive of Film, Photo, and Sound Documents of St. PetersburgHe made a great impression on everyone he met, many writing that he “looked like a meek simpleton not of this world, who had appeared on this sinful Earth.” One such meeting with John was recorded by Elizaveta Dyakonova in 1894 in her diary. She was one of the first feminists in Russia and not particularly religious: “I walked home, completely enraptured by my meeting with Father John. This quiet, meek priest personifies the ideal servant of God. His extraordinary personality exhales humility and infinite kindness.”

Even at the height of his popularity, John continued to eat almost nothing, serve the liturgy every day, give Holy Communion and keep almost no personal possessions. All the huge donations that came his way he distributed to the needy, leaving nothing for himself. His wife, reluctant to suffer such austerity, often complained to the church authorities that she had nothing to live on because her husband gave everything away.

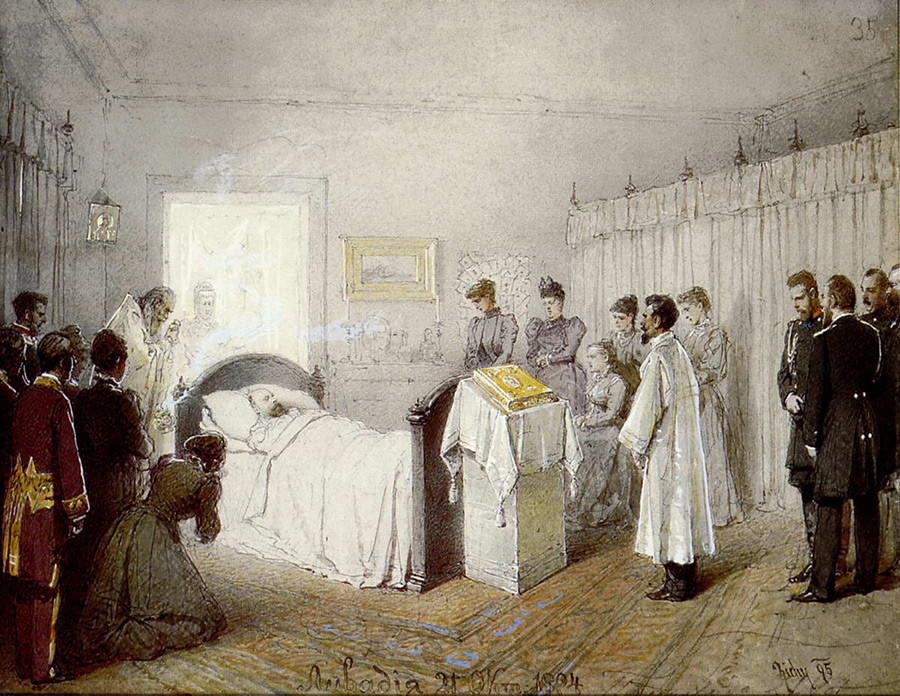

In 1894, John of Kronstadt was summoned to Crimea, where Emperor Alexander III was gravely ill. The tsar had his own personal confessor, of course, but out of desperation the “people's priest” was called due to his famed healing abilities. He was the only hope for the imperial family. John was with the tsar during the last hours of the latter’s life, saying prayers and performing rituals. “I had raised the dead, but could not prolong the Father-Tsar's earthly existence through my prayers to the Lord. May His Holy will be done...” John told the press afterwards.

Mikhai Zichi. The funeral service for the deceased Alexander III at Livadia Palace on Oct. 21, 1894 (pictured is not John of Kronstadt, but John Yanyshev, the tsar’s confessor)

Public domainThe great healer had failed to heal the emperor. This marked the peak of his priestly fame. His last function for the imperial family was to take part in the service after the coronation of Nicholas II, whereupon the door to the inner circle was closed.

“You can’t limp on both knees. And you can’t like Leo Tolstoy and John of Kronstadt at the same time,” writer Nikolai Leskov remarked pithily. Tolstoy and Kronstadt were the leading lights of late 19th-century Russia, as well as being irreconcilable foes.

The later Tolstoy developed his own view of religion. He ceased to observe and even rejected ecclesiastic rites, believing that intermediaries such as priests and the Church were not required for true faith. Finally, he denied the divine origin of Christ and the miracles he performed, considering them superfluous in the Bible.

Already enraged, this violation of the Church's canons was too much for John. The “meek” priest called Tolstoy “a heretic to surpass all heretics” and foretold that he would suffer “the savage demise of a sinner." “According to the Scriptures, you should be lowered into the depths of the sea with a stone hung around your neck; there is no place for you on Earth,” John said about Tolstoy.

In the late 19th century, the Orthodox Church, one of the pillars of Russia, was losing its influence, and society was in the grip of a crisis of faith. “The tragedy of the dispute was that both men were seeking ways to save the faith from its own crisis,” writes Pavel Basinsky in his book The Saint Versus Leo. John of Kronstadt and Leo Tolstoy: A Story of One Enmity (Elena Shubina publications, AST, 2013). Tolstoy believed that the faith needed saving from the Church itself, and urged people to pray by themselves. John, for his part, defended the Church “by spreading faith in [it] through his unique ministration,” writes Basinsky.

Read an exceprt from Pavel Basinsky's book here

Two deeply spiritual individuals, Tolstoy and Kronstadt became enemies due to their disparate views of how to heal the spiritual rift in Russia, but neither could do so. Ultimately, it was this schism in society that led to the bloodshed of revolution and civil war, altering forever the course of Russian and global history.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox