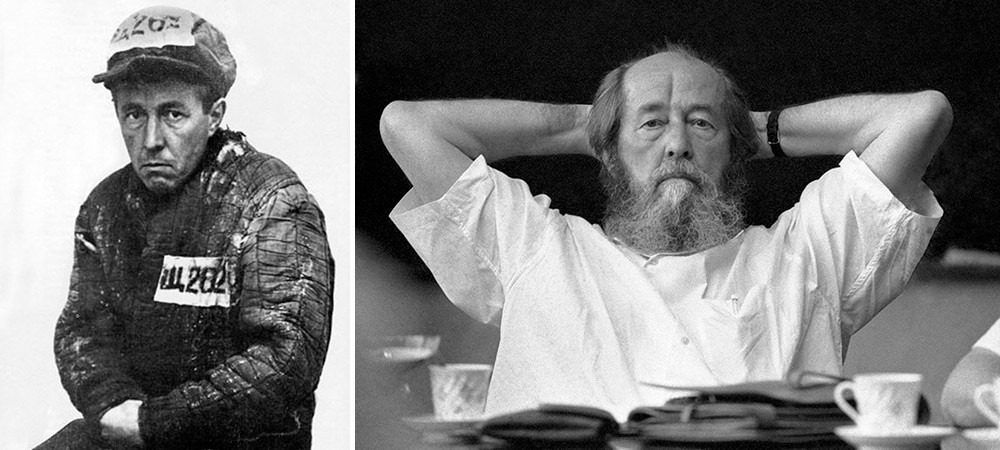

Varlam Shalamov, Alexander Solzhenitsyn and Osip Mandelstam - three writers put in the GULAG system.

Pixabay; Getty Images; OGPU USSRAs historian Viktor Zemskovnotes, in 1953 alone (the year of Stalin’s death) there were 5,4 million people in imprisonment – so the total number of people put there throughout Stalin’s reign (1924-1953) is far higher. Among the hundreds of thousands of victims, we chose six people remembered not only for their grim fates but for their outstanding careers as well.

Captain Solzhenitsyn was arrested in 1945 while serving in the Red Army for criticizing Stalin in his private letters. At first, he, being a mathematician, worked in the sharashkas – secret laboratories where conditions were relatively bearable. However, they soon sent him to the labor camps of Kazakhstan, where he witnessed astonishing injustice and violence.

After USSR’s next leader, Nikita Khrushchev, denounced Stalin’s personality cult in 1956 and disclosed facts of the repressions, Solzhenitsyn was rehabilitated - the state commission concluded that he committed no crime by expressing his opinion of Stalin in his letters, so he returned to Moscow. In 1962, he managed to publish the first ever story of a camp prisoner in the USSR: One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich which shocked the world and, eventually, led to the Nobel committee giving Solzhenitsyn a prize in literature in 1970.

The author continued with his struggle to reveal the truth, preparing a giant work on the stories and realities of the camps, The Gulag Archipelago. After years of oppression, authorities forced him to leave the USSR in 1974. He only returned twenty years later.

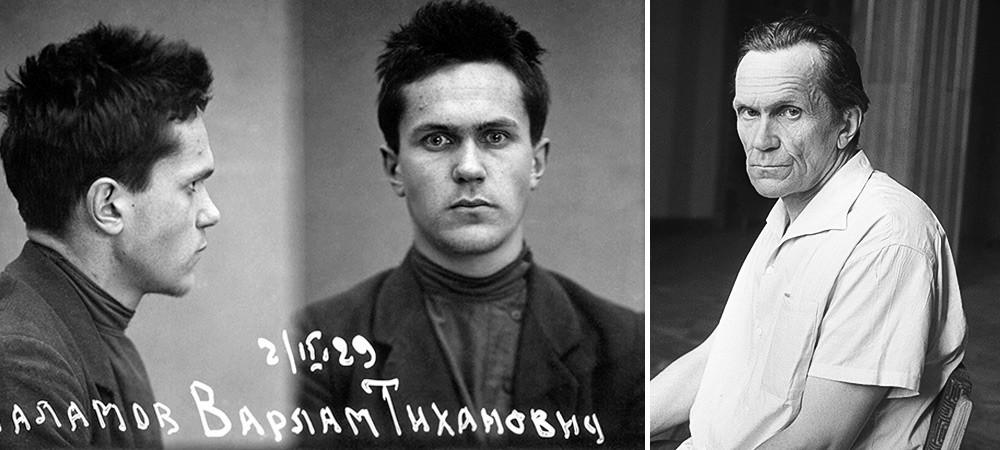

Another camp survivor writer, who depicted the inhuman nature of the imprisonment system. Shalamov depicted even darker worlds than Solzhenitsyn. After all, he spent 14 years in the GULAG system, being sentenced three times – for being a member of a Trotskyist organization. Most of that time he spent in Kolyma, a remote region in the Far East, infamous for its camps where prisoners had to mine gold and other metals in the very harsh climate with -40 Celsius winters.

The Kolyma Tales, a collection of short stories about life in the camps, remains one of the most terrifying books in Russian literature, showing life diminished to survival at all costs, degradation of any morals, people turning into animals because of cold, hunger and slave labor. “The camps are in every way schools of the negative. No one will ever receive anything useful or necessary from them,” concludes Shalamov.

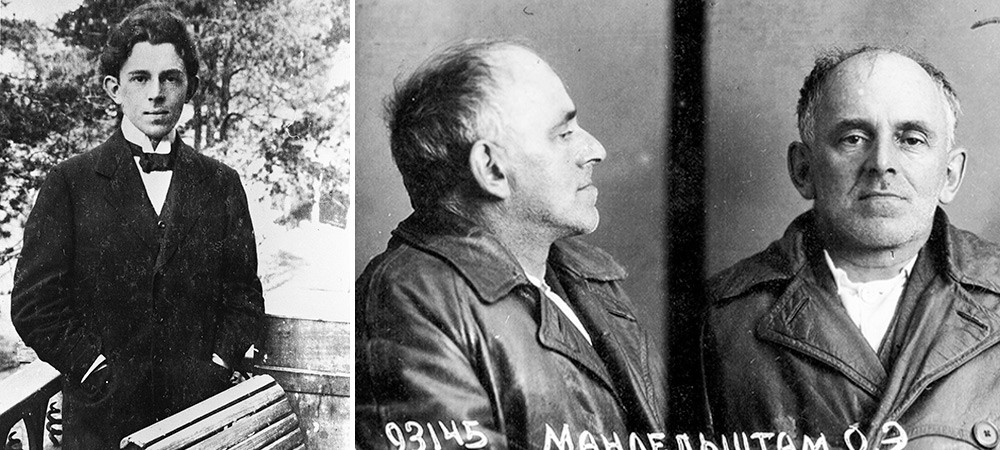

When Mandelstam, one of the most prominent poets of the early 20th century, wrote the ‘Stalin Epigram’ in 1933, his fellow poet Boris Pasternakcalled it “an act of suicide”. Indeed, such verses in the 1930s, when Stalin became almighty, sounded very suicidal:

We are living, but can’t feel the land where we stay,

More than ten steps away you can’t hear what we say.

But if people would talk on occasion,

They should mention the Kremlin Caucasian.

…

He is forging his rules and decrees like horseshoes –

Into groins, into foreheads, in eyes, and eyebrows.

Every killing for him is delight,

And Ossetian torso is wide.

‘The Kremlin Caucasian’ heard it well. Between 1934-1937, Mandelstam was exiled to Voronezh (500 km south of Moscow), then returned to Moscow but was arrested again. He was sentenced to 5 years in labor camps in the Far East for “anti-Soviet propaganda” and died of typhus on his way there, fully exhausted.

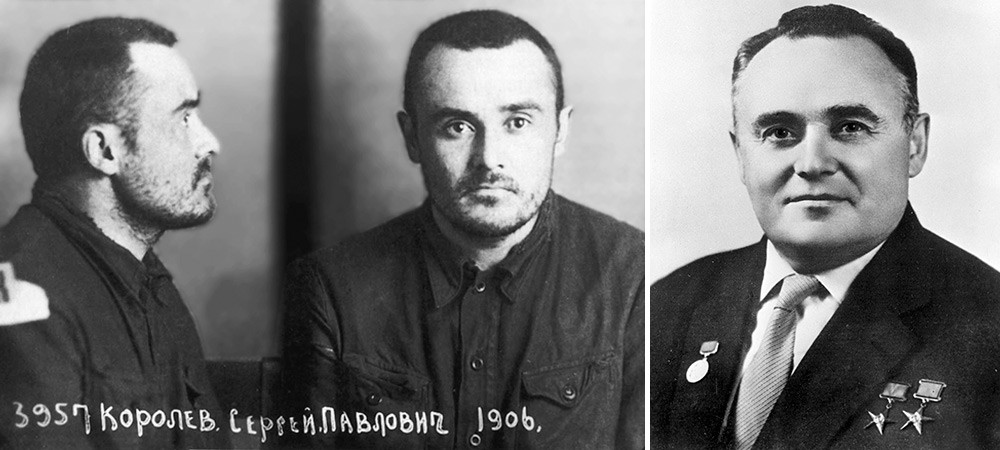

Scientist Korolev is an icon for every Russian working in the space industry. It was he who was responsible for the Soviet space program, which made the USSR a space superpower, launching the first artificial satellite in the orbit and then sending the first human into space in 1964. All of that would not have happened if Korolev had died in the GULAG, where he was put several years before.

In 1938, the authorities arrested Korolev and sentenced him to 10 (later reduced to eight) years at the camps for “sabotage”. He spent a year in Kolyma, where he survived torture and only sheer luck saved him from dying there. And then in 1940, he was transferred to work in a secret laboratory with other scientists deprived of their rights. Korolev worked on missile and space projects throughout the 1950s, but only in 1957 was he fully rehabilitated.

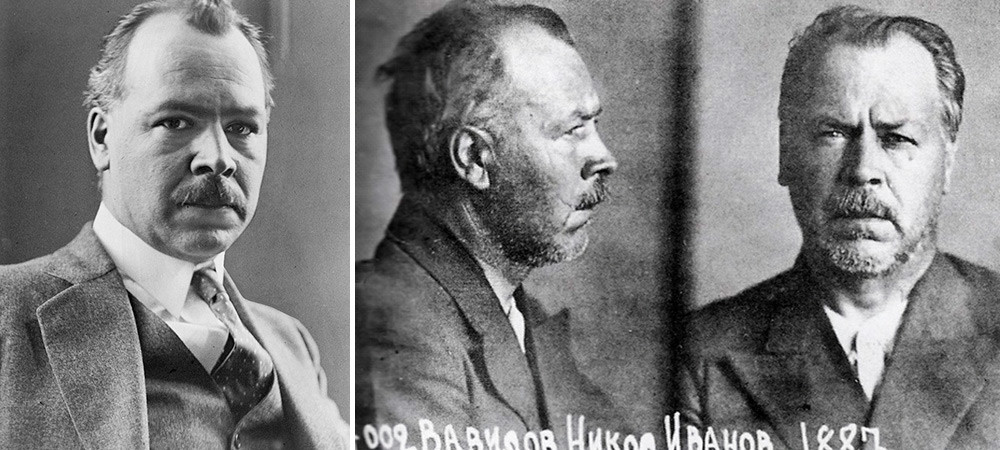

A geneticist and botanist who traveled the entire world (with the exception of Australia and Antarctica), Vavilov studied plants and their features, then worked in the Institute of Plant Industry, improving crops – wheat, corn, and others – and was devoted to science and the USSR. Nevertheless, it didn’t save him from the Great Terror of the 1930s. Genetics that he championed in was considered “pseudoscience” by Stalin, so punishment wasn’t far off.

They came after Vavilov in 1940 and a long chain of interrogations and torture began – he was forced to ‘confess’ not only sabotage but also creating a secret Labor Peasant Party (which was non-existent). Sentenced to death, Vavilov later witnessed ‘mercy’: in 1942, USSR’s Presidium of the Supreme Soviet replaced the death penalty with 20 years in work camps. The following year, Vavilov died in prison – only to be fully ‘rehabilitated’ posthumously in 1954. His “anti-scientific” research ended up contributing tremendously to the field of genetics.

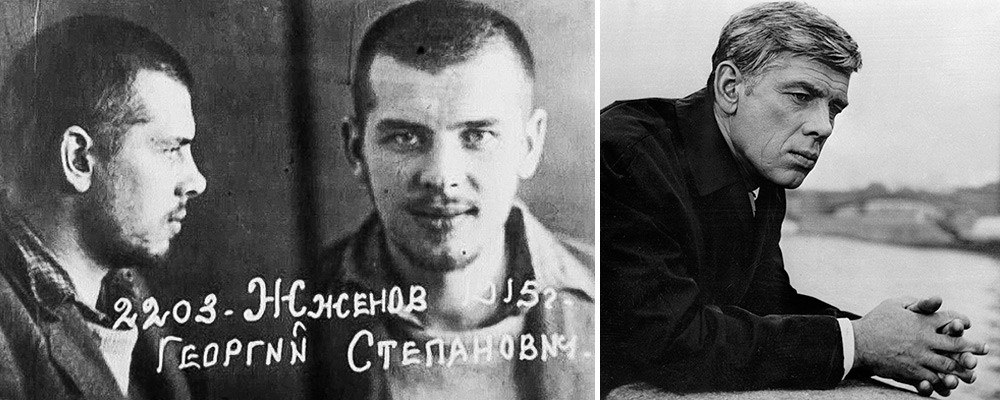

Before becoming a famous Soviet actor, Zhzhonov spent 14 years in prisons, camps, and exile - six of them in Kolyma, barely surviving it. “I had no illusions, no faith in justice or law… it was an every-hour struggle for survival, physical survival,” heremembered in interviews. What was his ‘crime’? On a work trip, 23-year-old Zhzhonov had met an American diplomat and spoke to him for half an hour.

Given the fact his older brother, Boris, had been arrested for “anti-Soviet activities”, Zhzhonov had little chance of fair trial. He was sentenced for “espionage” and sent to the GULAG. He managed to survive it and built a successful career in film after the rehabilitation. But he never forgave Stalin and his cruel regime.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox