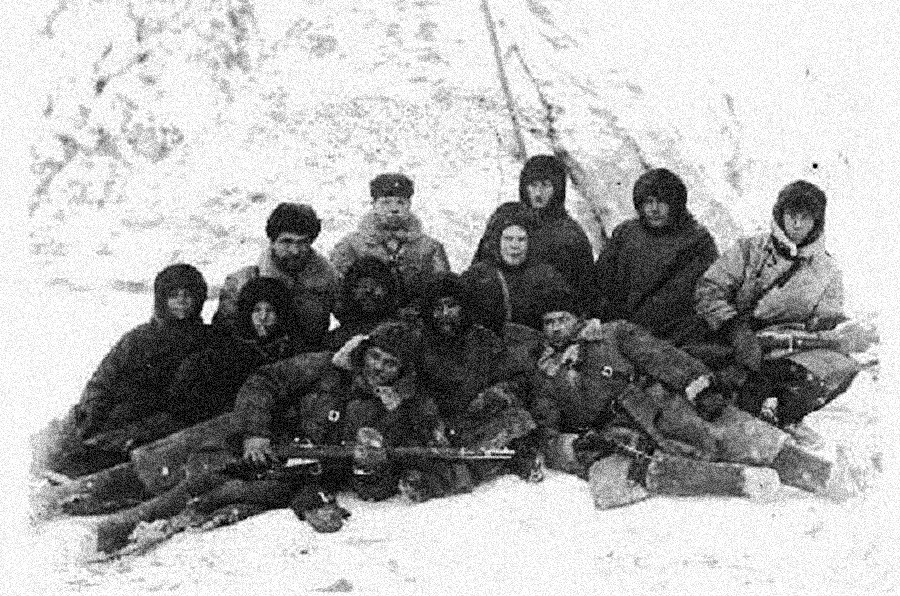

Soviet Military Guard after the rebellion's suppression.

Archive photoThe winter of 1942, in the very north of the Soviet Union in the Komi Republic, saw the first uprising in the history of the Gulag. Surprisingly, it was organized by the head, Mark Retyunin, of the Lesoreid logging camp near the village of Ust-Usa.

Retyunin had himself in the past been convicted for banditry. Having remained in the camp as a civilian guard, he soon became the chief administrator, maintaining good relations with both prisoners and security. But persistent rumors about an upcoming mass execution of prisoners “for counter-revolutionary activities” forced Retyunin to take action.

On Jan. 24, after disarming the guards, more than a hundred prisoners escaped from the camp and raided nearby villages and settlements, clashing with law enforcement officers and freeing prisoners from local holding cells.

After several skirmishes with units of the Military Guard, a paramilitary security service, the prisoners were defeated, and Retyunin shot himself. The law enforcement agencies lost 33 men, while among the rebels 42 were killed and a further 50 were sentenced to death.

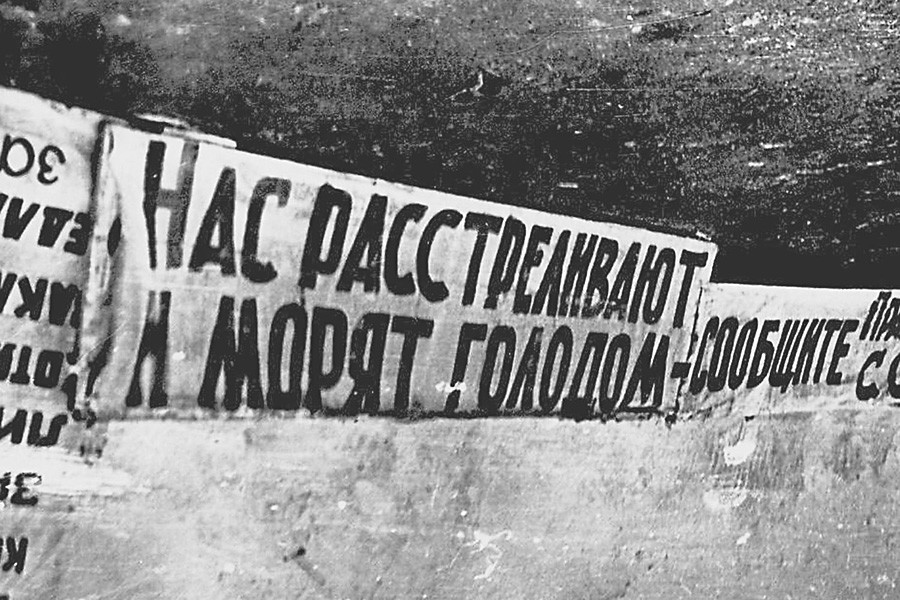

The poster says: "We are being shot and starved"

Archive of the Federal Security ServiceThe largest uprising in the history of the Gulag, which was more like a general strike, involved more than 16,000 inmates of a mountain camp near Norilsk.

After multiple executions of prisoners by guards, thousands refused to go out to work. Having set up their own self-administration, the rebels engaged in what was at first a bloodless confrontation with the authorities, demanding an end to the guards’ lawlessness, a change in the camp leadership, and an improvement in the camp conditions.

The administration did make some concessions. Letters and visits were allowed, but the basic demands were ignored, which forced the rebels to continue their strike.

Seventy days after the uprising began, on Aug. 4, 1953, the authorities decided to storm the camp, which resulted in the death of 150 prisoners. Nevertheless, the Norilsk uprising achieved its goal — the following year the camp was closed down.

"The Blood of Kengir" painting, 1993, by Yuriy Ferenchuk, one of the uprising's participants.

Bessmertny BarakThe most “international” uprising in the history of the Gulag. On May 16, 1954, more than 5,200 prisoners rioted in a steppe camp in the Kazakh village of Kengir. The reason for the uprising was the execution by a guard of 13 inmates who had tried to sneak into the women’s section of the camp the night before.

Among the rebels were Ukrainians, Balts, Russians, Germans, Poles, Hungarians, and even the odd American and Spaniard. They pushed the guards out of the camp and took control of it.

For a whole month the captured camp became a kind of revolutionary republic. The rebels organized their own administration and self-defense units, armed with iron bars and Molotov cocktails, and even intelligence, counterintelligence, and propaganda divisions. This was made possible because many of the prisoners had experience of military service in the Russian Liberation Army, the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, and the Baltic Forest Brothers.

The rebels’ calls to meet with the Soviet leadership and to improve the conditions of detention were ignored. On June 26, Soviet army and police units, using five T-34 tanks, carried out an assault that culminated in 46 prisoners being killed and the camp returning to the control of the administration.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox