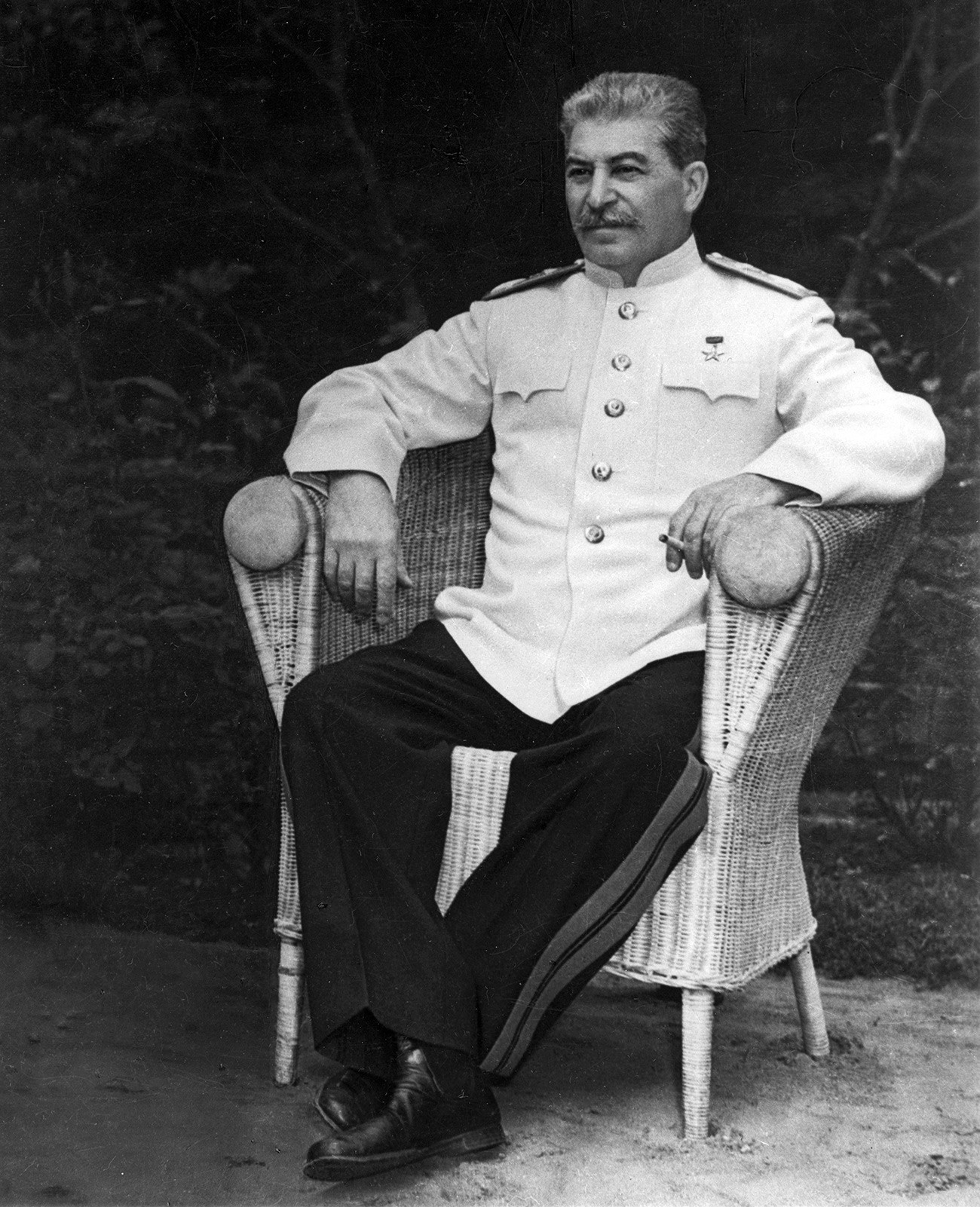

Joseph Stalin and Patriarch Sergius, who headed the Orthodox Church in the USSR while Stalin was in power.

Global Look Press, Legion Media, Public domainThere is a legend saying that it was a miracle that saved Moscow in the winter of 1941, when the Germans were approaching the city: Joseph Stalin supposedly ordered the powers of Orthodoxy to be harnessed to save his capital. “The miraculous icon of the Theotokos of Tikhvin was flown over Moscow in a plane. So the capital was saved,” reported Orthodox journalist Sergei Fomin in his book Russia Before the Second Coming.

Like any legend, this one is not true: there is no evidence that Stalin, a Bolshevik atheist, decided to resort to such a strange measure to defeat the enemy. It was the bravery and skill of the Red Army that saved Moscow in December 1941, not some kind of higher power. But legends of that kind remain popular: there is one about Stalin visiting Saint Matrona of Moscow, who promised him victory, or about him praying for the defeat of Germany.

These legends, though untrue, reflect the shift in Stalin’s religious policy during the war, which surprised the USSR and inspired rumors of the leader’s “secret Orthodoxy.” Two years after the Battle of Moscow was won, Stalin met with three chief hierarchs of the Russian Orthodox Church, allowed the clergy to perform religious services, celebrate Easter and Christmas, and even promised to give the church back some of its monasteries (confiscated after 1917) and release imprisoned priests. Basically, he made Christianity legal again, in an atheist country.

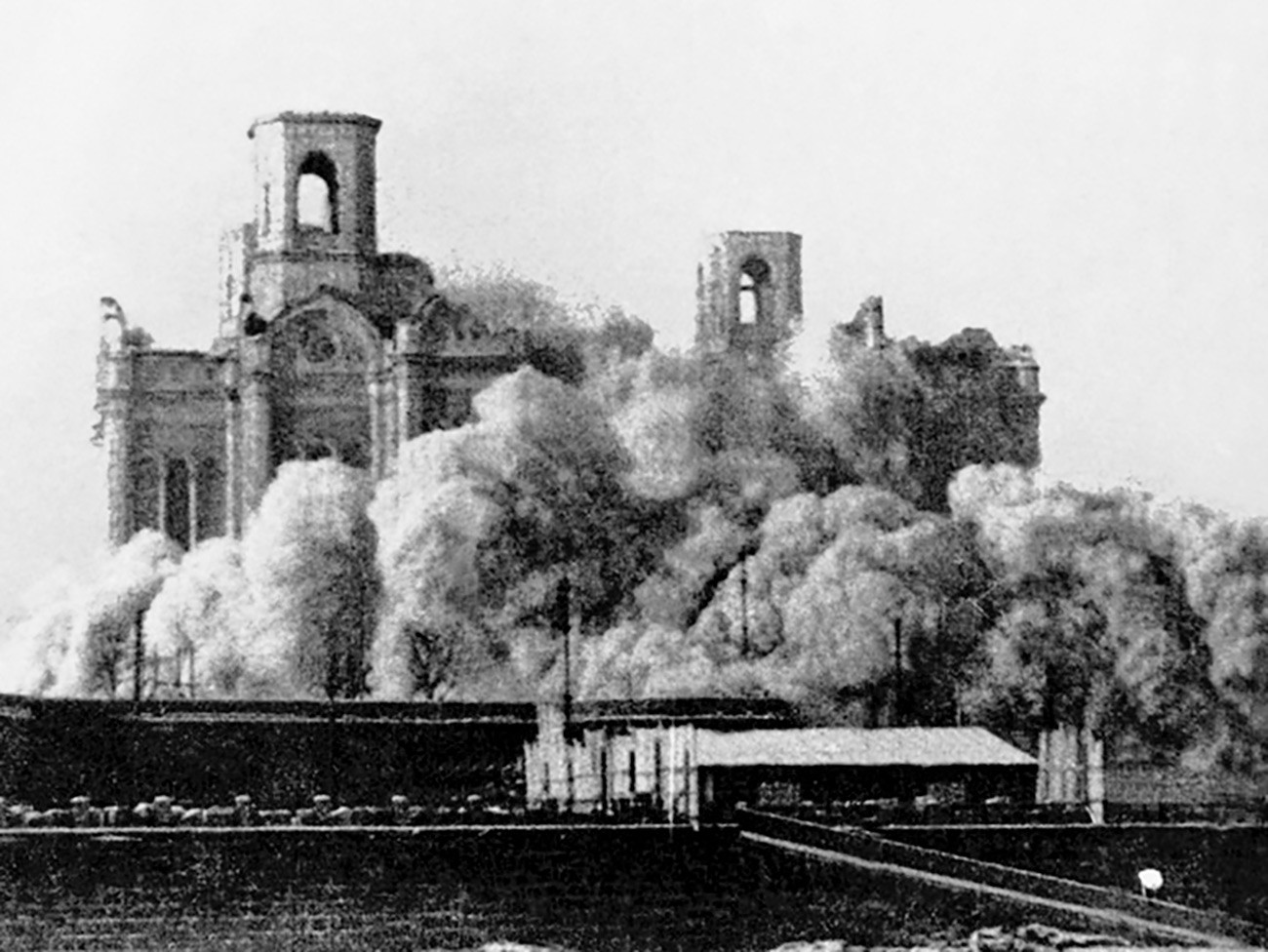

Blowing up the Cathedral of Christ the Savior in 1931.

russiainphoto.ruThe three hierarchs, led by Sergius (Stragorodsky), the Patriarchal locum tenens in 1925-1943 and de facto head of the Church, thanked Stalin after their meeting in a very servile letter: “In each of your words… we felt the heart that burns with paternal love for all his children... The Russian Orthodox Church venerates you feeling with your heart that it lives together with all Russian people, by the will to victory and sacred duty to sacrifice anything for the sake of the Motherland. God save you for years to come, dear Iosif Vissaronovich.”

The elite of Orthodox clergy in the USSR, 1930s.

Public domainPraise for the strongman was understandable: before 1943, the Orthodox lived in constant fear. Anti-religious propaganda flourished. Throughout the repressions of the 1930s, at least 100,000 people convicted in cases connected with the Church were executed. Being an Orthodox Christian (or believer of any other kind) in a country that worshipped only Communism meant living under a threat.

It’s important to remember that “dear Iosif Vissarionovich” was among those who carried out the anti-Church repressions. As priest Job (Gumerov) noted commenting on the legend of Stalin ordering an icon to be flown over Moscow, “Any attempt to present the cruel persecutor as a faithful Christian is dangerous and can cause only harm.” Indeed, Stalin wasn’t Christian, so why did he change his policy towards Orthodoxy?

Stalin, a cynical and clever leader, didn’t experience any epiphany but simply knew that taking it easy on the Orthodox Church was important for winning the war. First, many Soviet citizens remained secretly religious (which was not directly forbidden), so the “legalization” of Orthodoxy helped to keep the nation at war united – quite a crucial thing. Second, the Allies were pushing Stalin towards loosening his grip on the religious: the oppression of the faithful was bad publicity, internationally speaking. Third, in 1943 the Red Army was regaining the Soviet lands previously occupied by Germans. The occupants, trying to gain public support, had reopened churches closed by the Bolsheviks – and it would have been strange indeed had the liberators reclosed them.

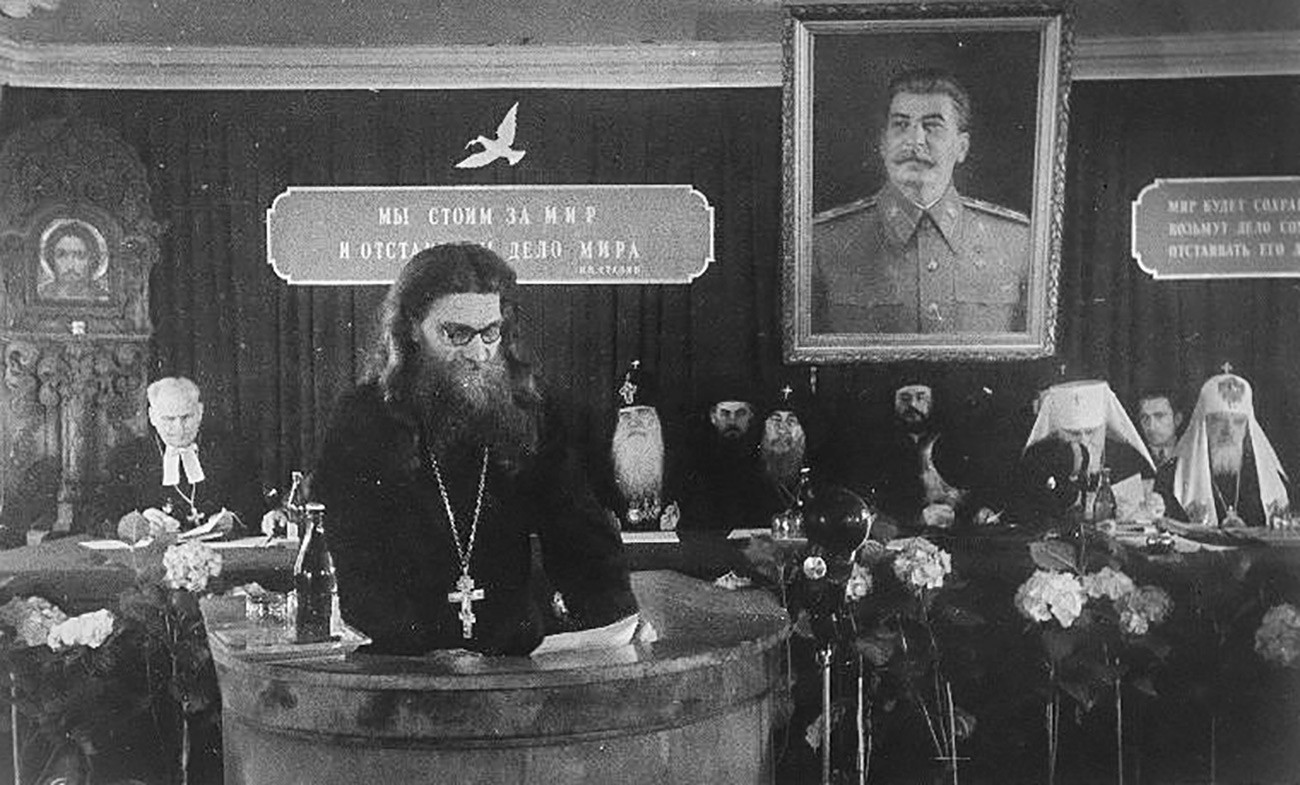

The clergy conducting their meeting under Stalin's' portrait, 1940s.

russiainphoto.ruStalin understood all of that and acted accordingly. His biographer, historian Oleg Khlevniuk, wrote: “Moving from the iconoclast approach of the 1920s – 1930s, from mass repressions against priests and believers to a reconciliation was a demonstrative, practical move. Such a shift in the Soviet policy towards religion is to be viewed within the context of encouraging Russian patriotism.”

A priest giving his blessing to the Red Army soldiers during the war.

SputnikStalin kept his promise to the Church hierarchs: in 1943, they held the first election of a Patriarch in 20 years, won by Sergius. In return for loyalty and support for the authorities, Stalin let the Orthodox Church be: of course, the state remained atheist but priests were not imprisoned and killed anymore. The next wave of anti-Church repressions occurred during the rule of Nikita Khrushchev, in the 1960s, but was far less blood-shedding.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox