It was fashionable among European monarchs in the 16th century to have an interest in occult studies such as alchemy and astrology. Even before Ivan the Terrible, his grandfather Ivan III (1440-1505) had been interested in the mystical properties of precious stones; as for Ivan Vasilyevich [Ivan the Terrible] (1530-1584), he kept soothsayers at court. He invited astrologer Eliseus Bomelius to come to Russia from England. Bomelius prepared poisons – which Ivan actively used to get rid of undesirable high officials – and made astrological forecasts. But Bomelius was cursed by Muscovites, who called him the "evil magus Bomelius", and considered him a practitioner of black magic. Bomelius was roasted alive on a spit after Ivan discovered that he had been spying for Sweden.

READ MORE: 7 facts about Ivan the Terrible, the first Russian tsar

But that did not affect Ivan's passion for astrology. According to traveler Jerome Horsey, over 60 soothsayers from Lapland were brought to Moscow. At Ivan's request, they used the stars to predict the success of his military campaigns and reforms. According to legend, the soothsayers also predicted the tsar's death, which occurred when he was playing chess, another of Ivan IV's well-known pastimes.

"The Italian envoy Calvucci draws the favorite falcons of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich", by Olexandr Litovchenko, 1889

Olexandr Litovchenko/Kharkiv Art MuseumOf all the types of hunting that the Russian tsars traditionally engaged in as a royal pursuit, Tsar Aleksey Mikhailovich (1629-1676), father of Peter the Great, preferred hunting with birds of prey, a sport which had come to ancient Russia from the East. An incredible sum of money - 75,000 rubles (the state budget was 1.3 million rubles) - was allocated each year to the royal sport of falconry. The tsar kept a falcon aviary in Moscow housing 3,000 birds of prey, and the Department (or Prikaz, as it was known) of Secret Affairs – the state security agency of the time – was in charge of hunting with falcons.

When the tsar was young, he went hawking almost every day. Members of the royal family and invited foreign guests took part in falcon hunts. The tsar traveled to the countryside outside Moscow – Sokolniki, Kolomenskoye or Preobrazhenskoye – where magnificent tents with refreshments would be erected in open fields by the riverbank or on a lakeshore.

At the tsar's signal, the servants blew horns and beat drums to put ducks and other game to flight. The tsar watched falcons and hawks fly up from the falconers' gauntlets, soaring high into the sky and then – the tsar was particularly fond of this part – dropping like a stone on their prey. After the hunt, the tsar was brought the falcon that had distinguished itself the most. Sometimes, Aleksey Mikhailovich performed the role of falconer himself – he was an expert on falconry and even contributed to a manual for training falconers (‘Uryadnik sokolnichya puti’.)

"Peter the Great in His Studio” by Konstantin Makovsky, 1870

Konstantin Makovsky/Hermitage MuseumIt is difficult to single out just one of the hobbies of Peter the Great (1672-1725) – after all, he mastered 14 crafts: carpentry, joinery, blacksmithing, cartography, shipbuilding… But Peter's favorite pastime was performing surgical operations. In Amsterdam, he visited the museum of the anatomy of Professor Frederik Ruysch and took lessons from him, and in 1699 inaugurated anatomy courses for the boyars in Moscow. According to the biographer of Peter, Ivan Golikov, the tsar ordered that he should be informed of operations and autopsies and "rarely missed such an event and an opportunity to be present… and often even helped perform operations. Over time he acquired such a level of skill that he became most adept at dissecting corpses, bloodletting and extracting teeth, and was very keen to perform such operations".

The collection of teeth pulled out by Peter the Great on display at the Kunstkamera

Public domainThe tsar always carried a case with surgical instruments with him and was ready to pull out someone's teeth at any opportunity. In the Kunstkamera in St. Petersburg you can see the entire collection of teeth pulled out by the emperor. And some of them were… healthy.

One person within Peter's inner circle in 1724 wrote in his diary that Peter's niece "is in great fear that the emperor will deal with her bad leg soon: It is well known that he regards himself as a great surgeon and willingly undertakes all sorts of operations on patients". We shall never know how good Peter was as a surgeon. First of all, nobody would have dared accuse the emperor of a patient's death and, secondly, after ascertaining the death of a patient, Peter used to say a quick prayer and, enthusiastically explaining his actions to all present, he would start to dissect the corpse. Anyway, his enthusiasm did benefit the country: the emperor was the founder of the Lefortovo Military Hospital, the first state hospital in Russia.

Peter was also the first professional collector. He laid the foundations of numismatics and the collecting of works of art in Russia. You can read our article on what Peter the Great kept in his treasury here.

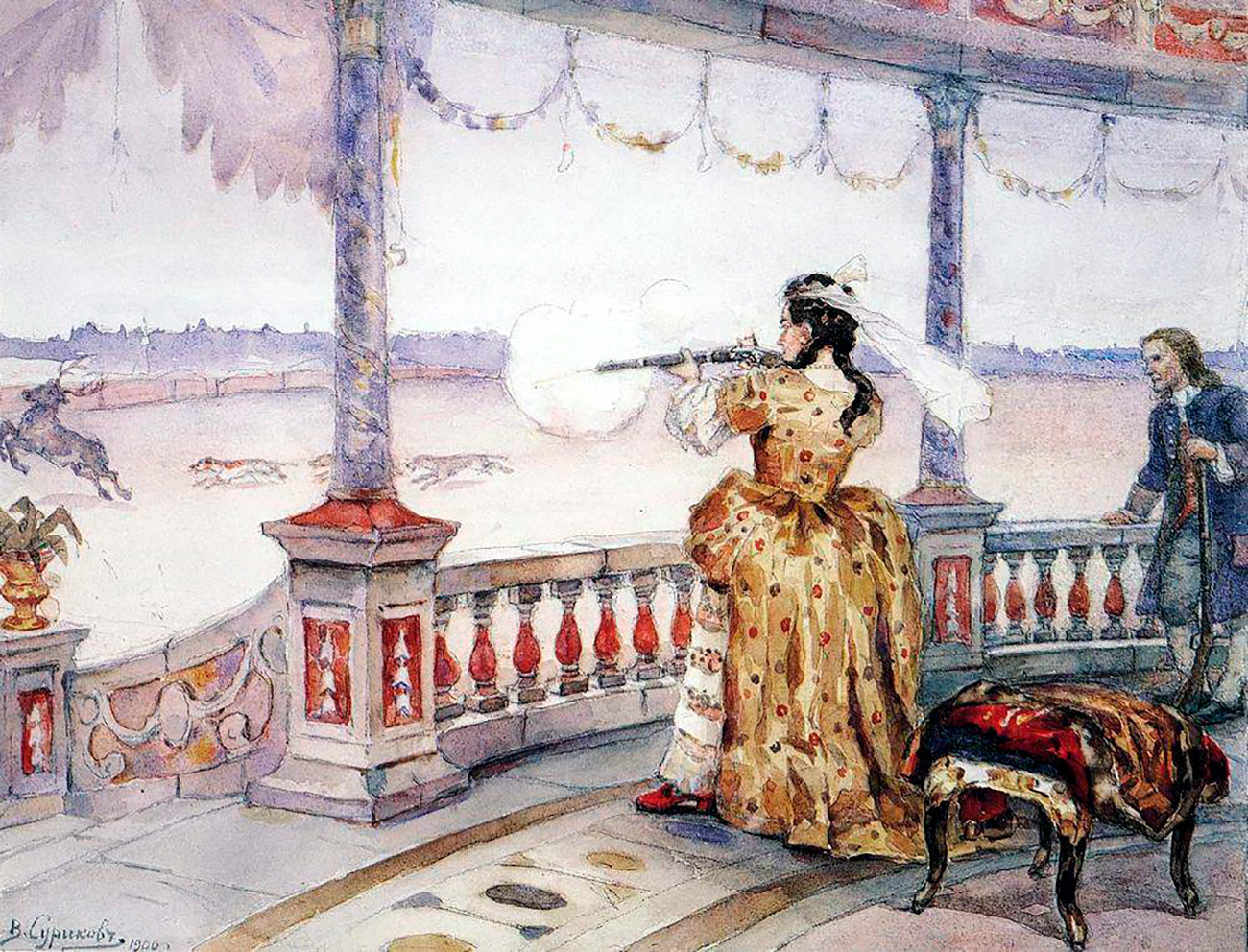

"Empress Anna Ioannovna shoots deer at the Temple pavilion in Peterhof," by Vasiliy Surikov, 1900

Vasiliy SurikovThe niece of Peter the Great, Anna Ioannovna (1693-1740), hated attending balls and the theater. She only turned up at such events when the weather was bad. Her real passion was going shooting. She was even nicknamed the "Peterhof Diana" as she turned one of the pavilions in Peterhof, a summer residence of the Russian emperors, into a hunting lodge. And directly behind it, in the Lower Park at Peterhof, there was a wildlife menagerie with large game animals – deer, roe, moose, and so on.

In addition, all kinds of game were brought from across the country to Peterhof and released straight into its park, where the empress liked to go on her walks with a rifle. Over the 1739 summer season, she shot nine deer, 16 wild goats, four wild boar, one wolf, 374 hares, and 608 ducks! There was even a small sporting rifle in the royal carriage as the empress enjoyed bringing down a duck or crow while careering along at top speed.

"Emperor Nicholas I and Grand Prince Alexander in the artist's studio in 1854," by Bogdan Villevalde

Bogdan VillevaldeFrom childhood Nicholas (1796-1855) had a penchant for drawing and, among the military sciences he was taught, he liked fortification and engineering – particularly technical drawings and sketching. They were the passion of the future emperor. He knew how to make copper engravings and loved to color them in with watercolors.

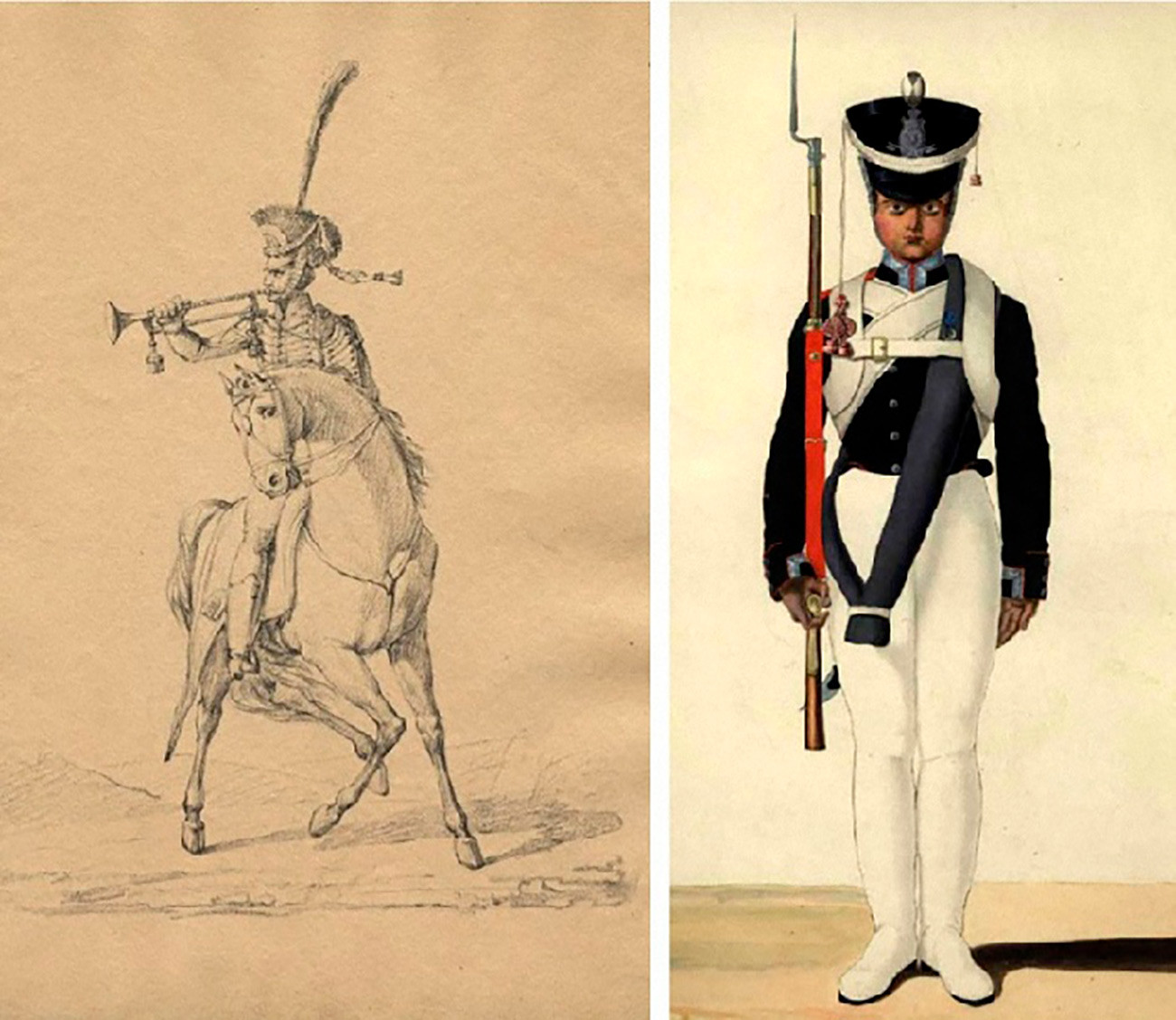

A copper engraving (L) and a watercolored copper engraving (R) done by Grand Prince Nicholas Pavlovich

Public domainDesigning military uniforms was another of his passions. While still a Grand Duke, Nicholas designed and drew dozens of sketches of Russian Army uniforms and, upon becoming Emperor, he put his ideas into practice – during his reign military and civilian uniforms were finally strictly standardized.

"Selfportrait as an Eastern horseman" by Grand Prince Nicholas Pavlovich

Public domainNicholas was also the first Russian tsar to play wind instruments. He owned a flute, a horn, a cornet, and a cornet-a-piston – actually, the tsar called all these instruments a “trumpet". He had a good ear and composed small marching pieces that he performed at home concerts.

Nicholas II watches as his camera is being placed on a tripod

Public domainNicholas II (1868-1918) was as good a draughtsman as his grandfather. He was also fond of cycling and lawn tennis. But the emperor's main hobby was photography. Thanks to this passion, we today have a better understanding of how the Imperial Family lived.

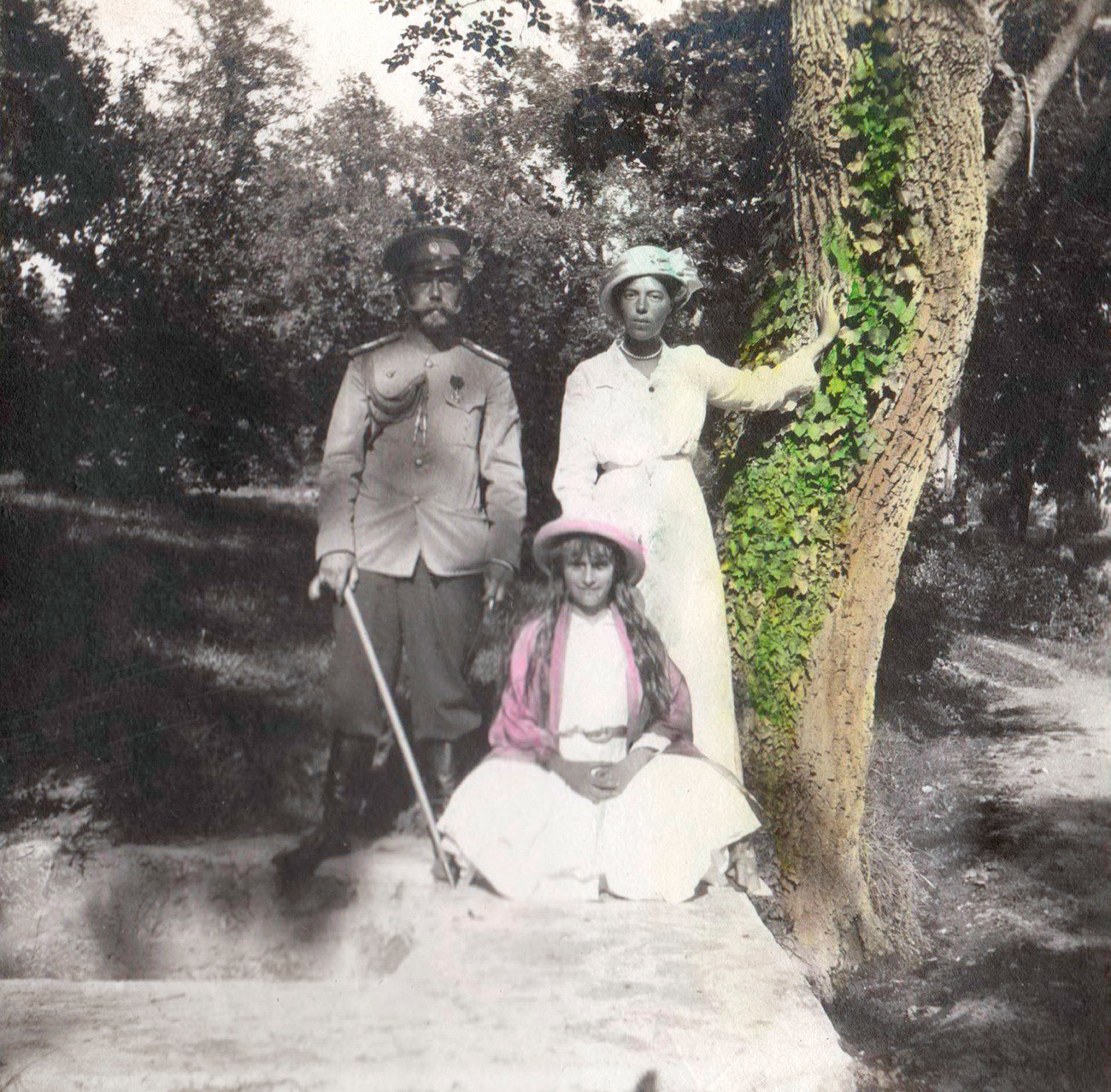

Emperor Nicholas II with his sister Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna and his daughter Grand Duchess Anastasia Nikolaevna of Russia. Сoloration by Anastasia Nikolaevna of Russia.

Public domainHe used an American Kodak camera, the best model of the time. His consort Alexandra Feodorovna was also fond of photography. The royal amateur photographers took and printed up to 2,000 pictures a year, and their daughters loved coloring in the black and white photographs. The family sometimes got together for their favorite pastime – labeling and pasting photographs into an album.

Nicholas II takes a selfie

Public domainThe imperial photos have survived thanks to lady-in-waiting Anna Vyrubova, who took six albums abroad and sold them to Yale student Robert D. Brewster, who then donated the archive to his university library – now all the photographs are in the public domain.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox