Foma and Erema, Russian folk painting

Archive photoAt first glance, a Russian skomorokh resembles a European troubadour. Traveling musicians and actors, the skomorokhs moved from one village to another, offering their entertainment services: performing at weddings and remembrance days, doing special shows for annual holidays, or performing their usual stage routine that included jokes, puppet theater, tricks with trained bears, and, of course, their song-and-dance acts. What could possibly go wrong?

Troubadours singing and reciting one of his poems, written in Occitan. 12th and 13th centuries. Colored engraving.

Getty ImagesSlavic people had a reputation of being especially good at musical performances. Constantine VII Porphyrogennetos (905-959), the Byzantine Emperor, wrote that in his palace, Slavic men were “used for making instrumental music”. In the Rus’, first mentions of skomorokhs date back to the 11th century. They played music and did shows at the feasts of the Russian princes, and later, Russian tsars. But skomorokhs also performed for simple folk.

Usually, a few weeks before skomorokhs would come into town, their future performance would have been advertised in the city’s market square. So when the artists arrived, the audience was already prepared and waiting. A skomorokh show included: глумление, (“gloumleniye”, “jeer” in English), a kind of cynical stand-up show that included obscenities and shocking content, even nudity. Adam Olearius, a 17th-century traveler, wrote that “traveling comedians, also known as skomorokhs, shamelessly bare parts of their bodies during their dances to entertain their audience, and the street fiddlers openly praise disgraceful deeds.”

'Skomorokhs' (1904) by Appolinariy Vasnetsov

State Tretyakov GalleryA puppet theater and trained animals also could be included in a skomorokh performance; another notable part were the старины (“stariny”, “oldies” in English) – well-known “hits” that Russians knew and loved. What were they about?

'Skomorokhs' fresco (1037) in the Saint Sophia's Cathedral, Kiev

Alexey Poddubnyi/TASSSkomorokh songs were naturally rhymed stories told against the backdrop of a band. One story is about a wealthy merchant named Terentiy and his unfaithful young wife, who said she was “sick between the legs” and sent her husband downtown to get medicine. Downtown, Terentiy met a band of skomorokhs that, on hearing his story, went down to Terentiy’s wife, only to find her home, healthy, and with her lover. After that, Terentiy most comically beats his wife’s sweetheart with a lead rod and steals his jacket. The whole song is filled with comical clauses and obscene words.

Another story is a hilarious surreal tale about a peasant whose house was robbed by a giant mustache; absurd imagery was very popular, while some songs were just long jokes. And what was the music like?

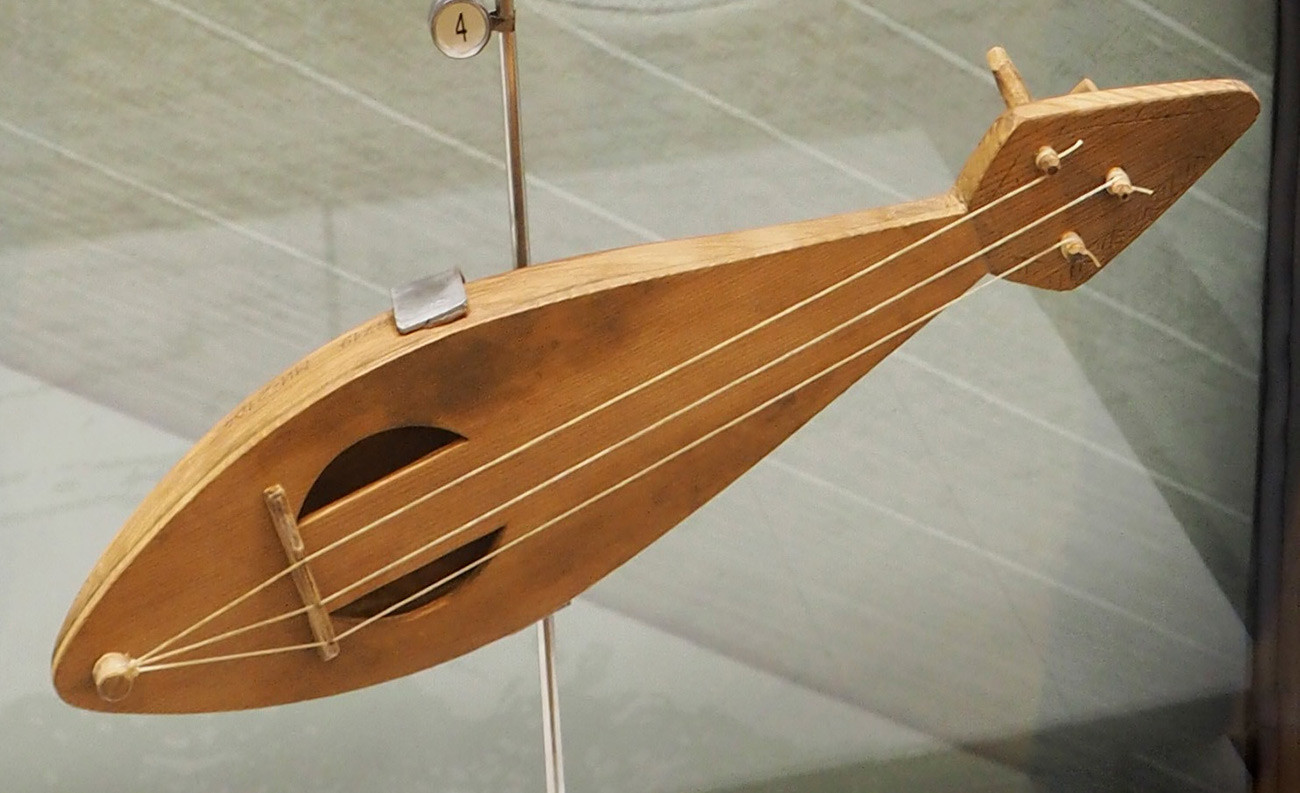

This is how a 12th-century gudok looked like

Andreykor (CC BY-SA 4.0)Skomorokhs used an array of instruments that could be easily brought on the road. Portable timpani drums, tambourines, and various other percussion; all kinds of wind instruments, including pipes, reeds, flutes and, most notably, zurnas, a wind instrument native to Central Eurasia. The domra and bass domra, folk string instruments of the lute family, were ‘guitars' of those times. When Adam Olearius wrote of “fiddlers”, he most surely meant people who played the gudok, a string instrument played with a bow. A wheel fiddle (now known as a hurdy-gurdy) was another popular instrument skomorokhs played, that professional story-tellers who sang epic ballads used. Gusli, a Slavic zither, was another instrument of traveling rhymers.

'Frog Princess' by Viktor Vasnetsov

Viktor Vasnetsov House MuseumHowever, the skomorokhs’ most important function, historians assume, was ritual performances on certain occasions like: weddings; Saturdays of Souls, which the Slavs celebrated about 5 times during a year; Winter and Summer solstice celebrations. Solstice feasts were very important for medieval people, as they allowed them to calculate time, which was necessary for successful vegetation of plants, and, eventually, survival. As we can clearly see, skomorokhs took part in celebrating these ancient pagan feasts. And that’s why the Russian Orthodox church was against them from the very beginning. The Russian Orthodox clergy and spiritual writers called the songs of skomorokhs “devilish” and “satanic”. And of course, skomorokhs were drawing people from the churches and to their shows, and the church wanted to stop this.

The leather masks of 12th-century skomorokhs

Shakko(CC BY-SA 3.0)In 1551, the Stoglavy Sobor (Council of a Hundred Chapters, a Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church) was held in Moscow to update ritual practices and condemn the sins by the clergy and the laypeople. Among the decrees issued by the Stoglav were several about the skomorokhs. These decrees show that the church had officially started a war against them.

Stoglav’s texts say that in the 16th century, skomorokhs were always present at Soul Saturdays, and because of them, Russians began singing and dancing at gravesites (apparently, as they also did in the pre-Christian times) instead of mourning. Also, skomorokhs were present at every wedding ceremony, and awkward situations would occur when the wedding procession arrived at the church, where pagan musicians would meet with Orthodox priests – a real clash of religions.

Russian ancient hurdy-gurdy

Mihail PapushStoglav banned all these practices and ordered Russian Orthodox priests to restrain their parish from inviting skomorokhs to their homes. Also, skomorokhs would take part in solstice celebrations, when, quoting Stoglav, “men and women gather for night bathing and lewd talks, devilish singing, and dancing, profane deeds, corruption of lads and maidens.” Stoglav also ordered these celebrations banned, but thus far, it was only a church order.

Skomorokhs in the village, 1857

F. RissIn 1648, tsar Alexis of Russia issued a prohibiting charter that banned all skomorokhs and pagan celebrations, and even introduced a penalty: the first and the second time anybody was caught listening to skomorokh music or dancing with skomorokhs, they were to be punished corporally; third time they were to be exiled to faraway towns. Thus, the pagan music went underground, and slowly through the course of the 17th and 18th centuries, disappeared. But some relics of those times have lived on – for example, bear-walking.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox