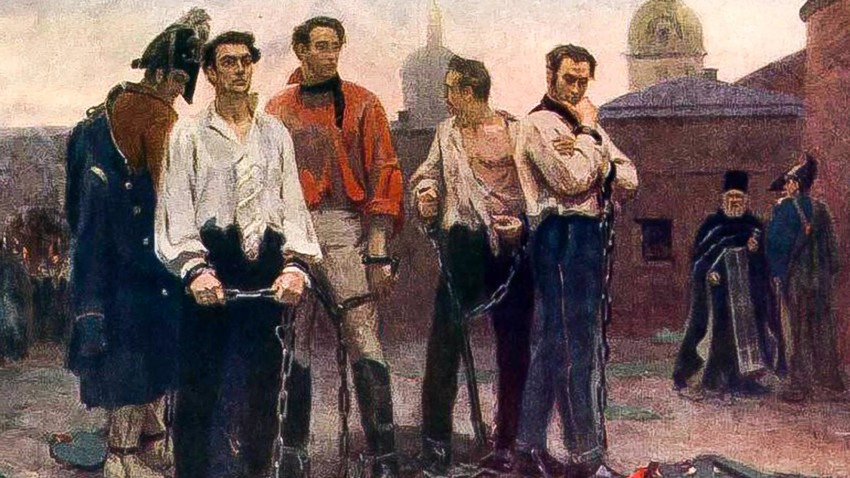

The execution of the Decemberists

Semen Levenkov

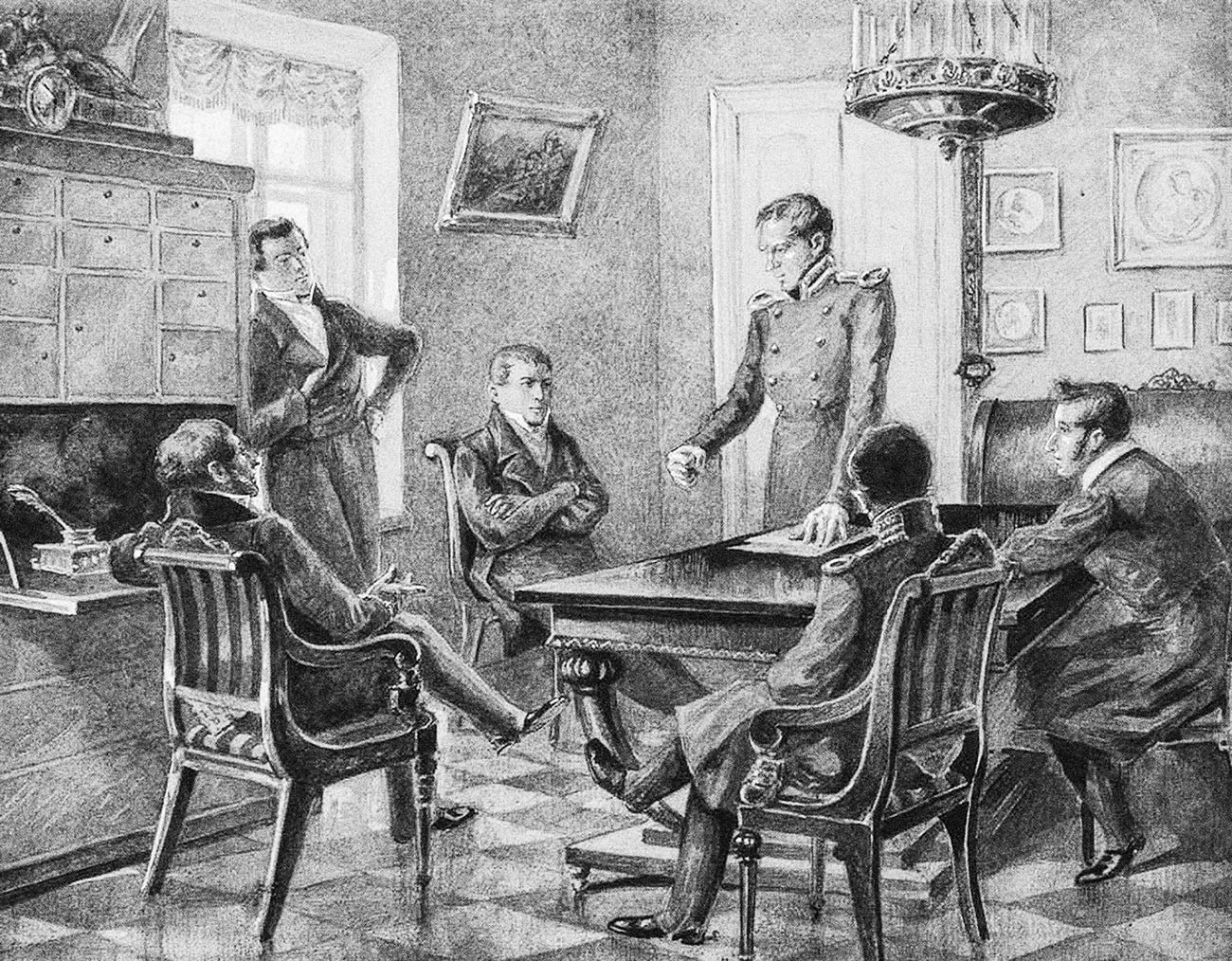

Pavel Pestel speech at the meeting of the Northern Society of the Decembrists in Petersburg

Getty ImagesThe Decemberists were Russian military officers and noblemen, who were members of different anti-government secret societies and eventually organized the Decemberist revolt of 1825. In total, there were over 600 Decemberists and their sympathizers. Among them were members of the Empire’s highest aristocratic families: royal guards Alexander Muravyov and Nikita Muravyov, Prince Ilya Dolgorukov, Prince Sergey Trubetskoy, and many other young noblemen. Poet Alexander Pushkin, the tsar’s advisor Mikhail Speransky and General Alexey Yermolov were also close to the Decemberist circles; some of them barely evaded punishment for that.

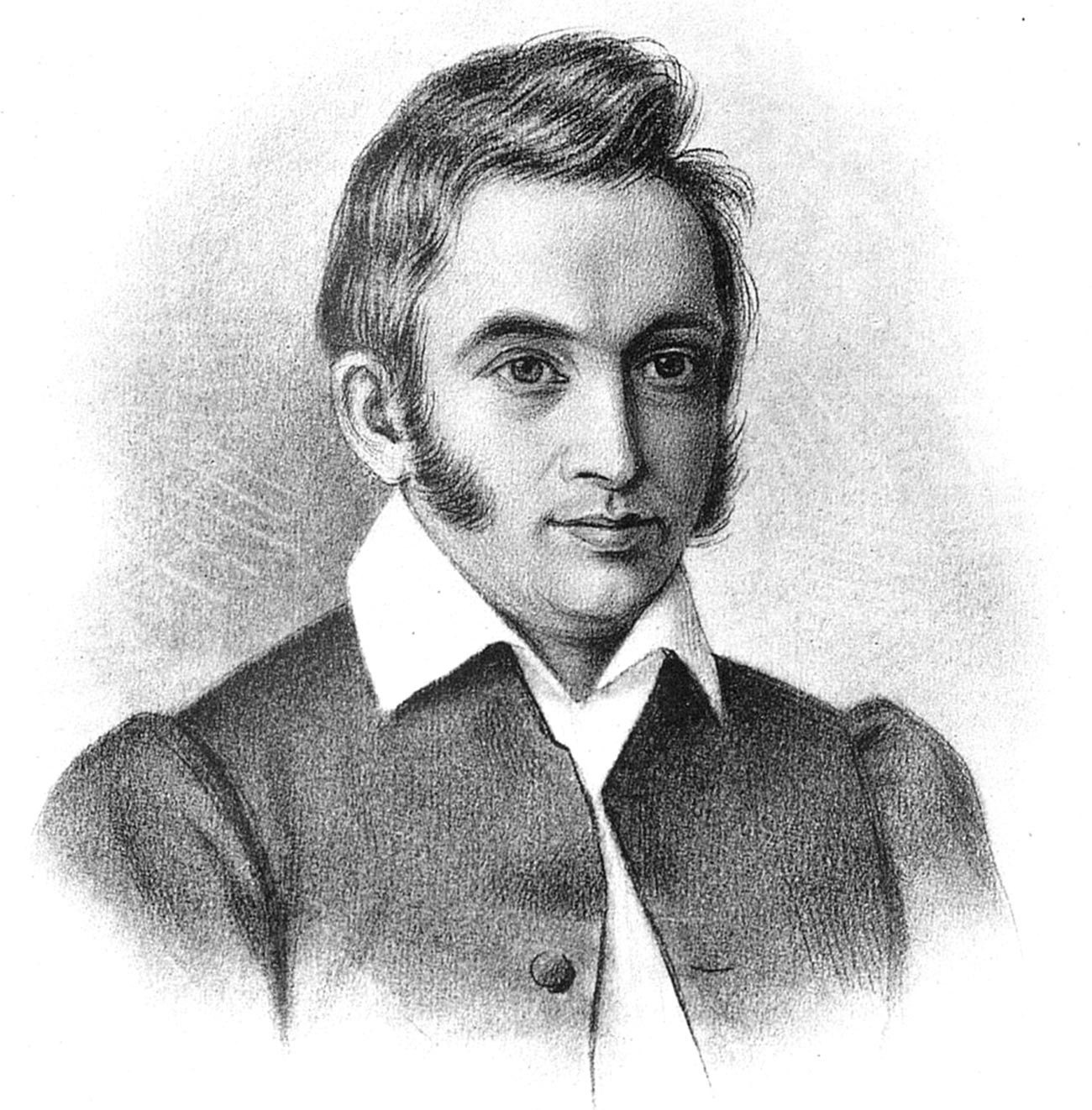

Nikita Muravyov

Pyotr GolovachevOn December 14th, 1825, the officers led about 3,000 soldiers in an uprising against the new Emperor, Nicholas I, who had ascended to the throne the day before the revolt. However, the uprising was suppressed by the army. Many people died. 579 noblemen were under investigation, 316 were arrested and 121 went on trial. Five were hanged, and others were exiled and suffered different penalties. Apart from the noblemen, over 4,000 soldiers were also punished through exile of their regiment to the Northern Caucasus.

Pavel Pestel

Pyotr GolovachevThe Decemberist leaders wanted to overthrow the Russian government and regime, arrest the tsar and the royal family, and then… Their two main documents, which contained the blueprints for the future political system, would serve as their foundation going forward.

According to ‘Russkaya Pravda’ (Русская правда, “The Russian Justice”; a name borrowed from the ancient Russian code of laws) by Pavel Pestel, the most radical among the Decemberists, Russia was to become a republic with a provisional government made up of respected people, and the tsar’s family was to be physically removed in order to prevent any restoration of the monarchy. The second document, Nikita Muravyov’s ‘Constitution’, declared Russia a constitutional monarchy, with the tsar playing only a representative role. Any further plans were really vague, as the Decemberists were very doubtful about the fate of their revolt and had postponed it for years.

The Senate Square in St. Petersburg on December 14, 1825

Public domainDuring the eventually victorious War of the Sixth Coalition (March 1813 – May 1814), the Russian army marched through Europe and back. The officers and the soldiers saw with their own eyes the lives and days of European peasants, townsfolk and the nobility. Many noble Russians returned home with a desire to change things – to liberate the serfs and to introduce a constitution in Russia.

These ideas were inspired by the French Encyclopedists, and by the American Constitution (the Constitution written by Nikita Muravyov was essentially a rough translation of the United States Constitution). Constitutional ideas loomed in the first years of Alexander I’s rule, but after the victory over Napoleon, Alexander gradually turned away from any kind of reforms in Russia. Although the Emperor knew about the secret societies and their constitutional ideas, he accentuated his disapproval of such ideas and, in 1822, banned all secret societies in Russia. The Decemberists saw the overthrow of the monarchy in Russia as the only way to execute their plans.

Grand Duke Konstantin

Public domainSince 1814, the future Decemberists created several secret societies that had proclaimed their goals as: eradicating social vices, fighting corruption and aiding the enlightenment of the masses. The Union of Salvation (1816-1817) was transformed into The Union of Prosperity (1818-1821). It had over 200 members and about 15 regional “branches”, but only the upper 30 members knew they had a constitutional coup d’etat planned in the future. By 1821, the Union of Prosperity became so widely known among the nobility, it had to be dissolved. It split into the more radical Southern Society in Kiev, led by Pavel Pestel, and the more liberal Northern Society in St. Petersburg, under the command of Nikita Muravyov.

By autumn 1825, both societies had come to an agreement that the coup d’etat was to be executed in summer 1826 – Emperor Alexander and both his brothers Konstantin and Nicholas were to be arrested during major military training in the southern parts of Russia, and at the same time, a military uprising was to be organized in St. Petersburg. But on November 27, 1825, news had reached St. Petersburg that Alexander had suddenly died on November, 19, while on wellness holidays in Taganrog, Russia. Because of the new circumstances, the Decemberists’ plans had to again be changed in a hurry.

Emperor Nicholas I

F. Krueger/HermitageAfter Alexander died, Russia spent two weeks at an interregnum. According to the Russian laws, Konstantin was the next in line to the throne; but in 1823, Konstantin signed an abdication from the throne – secretly, in order not to cause a stir in the society. The throne was to be transferred to Nicholas, but he didn’t know it – only three people in the Empire, Alexander’s trusted officials, knew about the abdication.

Immediately after the sad news was received, Nicholas, and all officials, the army, and people in St. Petersburg started swearing their formal allegiance to Konstantin as the new Emperor, and an official letter was sent to him to Warsaw where he resided. Konstantin replied to Nicholas, writing that he abdicated years before, and bluntly refused to do anything. But the messages went slow those days – Nicholas received Konstantin’s reply only on December 7; during all this time, Russia thought Konstantin was its new Emperor. Nicholas understood then that had to assume power himself. On December 13, he announced his decision and planned the new oath of allegiance to be performed the next day, December 14.

The Decemberists understood that this was their last chance to seize power. Nicholas had a rotten reputation among the army, including some of the royal guards, for his rigor and faultfinding. The Decemberists planned to interrupt the swearing of allegiance in St. Petersburg. The officers were to incite the soldiers of the royal guards to revolt, take the Winter Palace, arrest Nicholas and his family, and declare a Provisional Government. Prince Sergey Trubetskoy was chosen as the “dictator”, the revolt’s leader.

'The Decemberist revolt' by Vasiliy Timm

Vasiliy TimmOn December 14, various Decemberists had failed in their missions. After Pyotr Kakhovsky refused to sneak into the Winter Palace and kill the tsar, Alexander Yakubovich refused to lead two regiments to take the Winter Palace. Also, Yakov Rostovtsev, one of the Decemberists, had informed Nicholas about the plan of the revolt.

On the morning of December 14, the Decemberists officers raised three regiments to a revolt against Nicholas – the royal guard soldiers, more than 3,000 in total, marched to the Senate square in St. Petersburg, just minutes from the Winter Palace, and simply stood there doing nothing. Prince Trubetskoy, the dictator, somehow failed to appear on the square. The Decemberists were in a tight situation, they had to choose a new leader right on the spot.

"The shooting of general Miloradovich on December 14, 1825" by Vasily Perov

Vasily Perov/State Religion History MuseumMeanwhile, loyal army regiments twice attacked the revolting ones, but they withstood the onslaught. The square was filled with crowds of onlookers. Several people, including Grand Prince Mikhail and general Mikhail Miloradovich, the military governor of St. Petersburg, had appeared before the revolting regiments, pleading for them to surrender, but to no avail. Miloradovich was killed right there by the Decemberists officers. Emperor Nicholas later said to his brother Mikhail: “The most surprising thing about this story was that you and I weren’t shot.”

Before it went dark, Nicholas finally ordered buckshots and cannons to be fired against the regiments, which then quickly dispersed. The revolting soldiers fled the square and ran to the Neva River, where they tried to organize a military formation right on the ice and attack the Petropavlovskaya fortress. Many drowned because the cannonballs broke the ice. The 19th-century internal intelligence reports state that in total, 1,271 soldiers, officers, and civilians were killed that day, but the numbers were most likely higher.

Nicholas I in front of the Life-Guards Sapper Battalion near the Winter Palace on December 14, 1825

V. N. MasutovIn 15 days, in the Kiev Governorate, another Decemberist revolt happened – the one organized by the Southern Society. After the news about the December 14 revolt had spread across Russia, Sergey Muravyov-Apostol, one of the Decemberist leaders, was arrested in the village of Trilesy, but freed forcibly on December 29 and led an uprising of the Chernigov Infantry Regiment. The revolt was suppressed by the loyal forces on January 3, 1826, and Sergey Muravyov-Apostol was taken into custody.

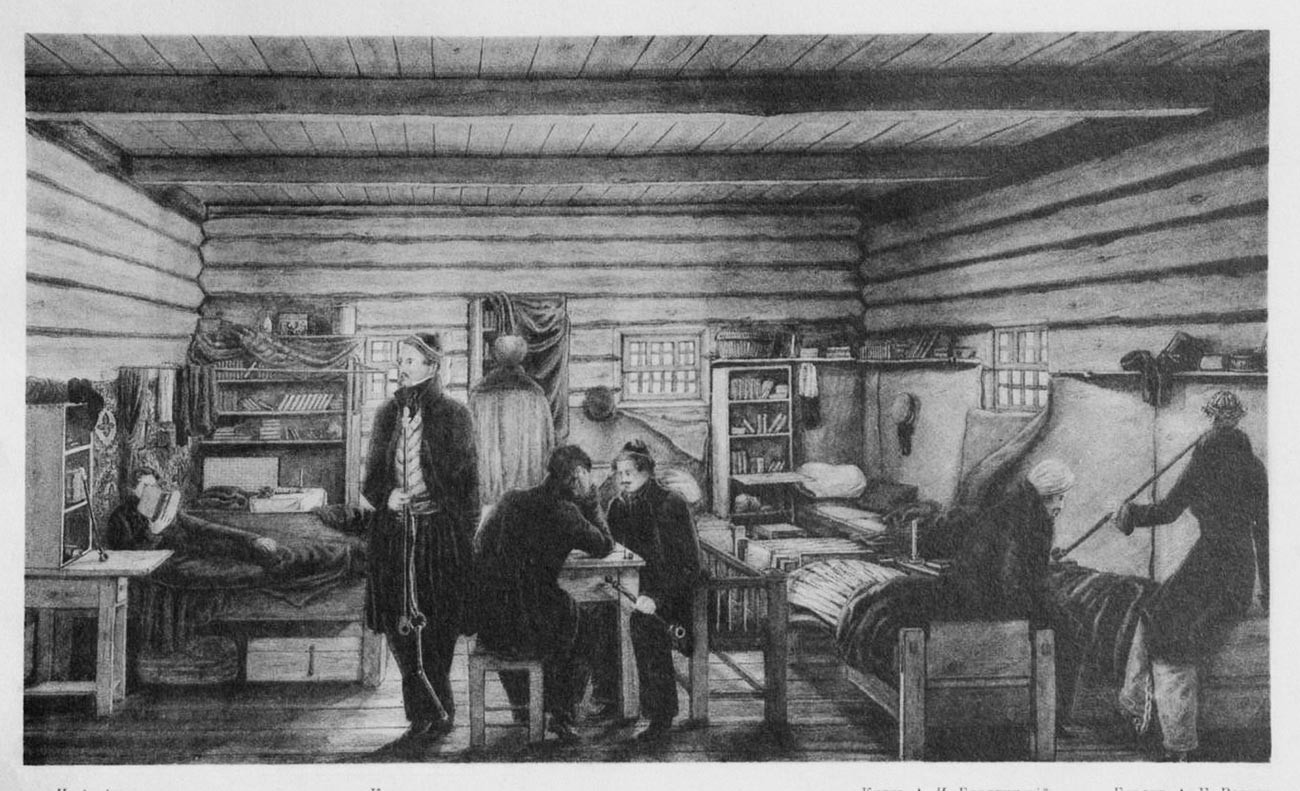

The Decemberists' cell in Chita, Siberia

Pyotr GolovachevThe investigation was very thorough: all members of the Decemberist conspiracy were interrogated, some of them by the Emperor himself. Their statements, including their explanations of their goals, their critique of the government and their constitutional plans were recorded into several volumes. Nicholas later repeatedly referred to these materials during his rule. He even ironically called the Decemberists “my friends of the 14th”.

In total, 121 noblemen were condemned to different penalties and sentences. 5 of the Decemberists’ leaders were sentenced to death by hanging (a shameful death for a nobleman), which was performed in secret on July 13, 1826. Within a week, the Decemberists sentenced to various terms of Siberian exile started leaving St. Petersburg.

The different sentences for Decemberists included: being stripped of nobility, lifelong hard labor, demotion of officers into soldiers, exiled to serve in the Caucasus, exiled to live in Siberia, and others.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox