Grand Duchess Anastasia Nikolaevna of Russia

Public domain

Grand Duchess Anastasia Nikolaevna of Russia

Public domainWe cannot tell for sure why exactly Anastasia was “chosen” by public gossip, but probably because she was the youngest daughter of Emperor Nicholas II and Alexandra Fyodorovna – born in 1901 the fourth daughter in the family, she was only followed by Alexey, the long-awaited heir, in 1904.

There are no clear accounts or written evidence of anybody in particular creating this legend. In Russian history there have been many impostors, promoting themselves as miraculously rescued royals: there were three False Dmitrys (all of them impersonating the son of Ivan the Terrible), and Emelyan Pugachev, the Cossack revolutionary of the 1770s, who claimed he was Peter III, who had escaped murder.

Empress Alexandra Fyodorovna with Anastasia as a toddler.

BundesarchivBefore Anastasia was born, her mother, Empress Alexandra, was very concerned with conceiving an heir. She already had three daughters; but according to the Russian laws of succession, a Grand Duchess could inherit the throne only when all male lines of inheritance had ended. Thus, Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich, Nicholas II’s younger brother, was the next in line of succession, which didn’t fit the ruling family, and Empress Alexandra in particular.

Nizier Anthelme Philippe, the quack hypnotizer

Public domainAlexandra dived deep into philistine mysticism. In 1901, a hypnotizer and charlatan named Anthelme Nizier Philippe appeared at the Russian court. Philippe’s methods were really ‘impressive’: for example, he gave as a present to Alexandra an icon with a tiny bell that would ‘alarm her when people with ill intentions would approach her.’ Philippe also “predicted” the birth of a son, and soon, Anastasia was born, to the disappointment of many people in the royal family (with the exception of her mother and father, of course). “Alix gave birth to a daughter – again!” – Maria Feodorovna, Nicholas’s mother, wrote to her daughter, and Nicholas's sister, Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna.

Nicholas II offers Anastasia a drag from his mouthpiece that holds a cigarette.

Public domainThere is not much information about Anastasia’s private life, mainly because it wasn’t something special or much different from the lives of the other daughters of the tsar. Anastasia was formally educated at home, although she wasn’t a diligent student. She loved singing and dancing, and frequently painted watercolors.

Empress Alexandra, Tatiana Nikolaevna end Anastasia Nikolaevna during WWI

Public domainDuring WWI, Anastasia, just like her sisters, volunteered as a nurse right in the royal palace at Tsarskoye Selo – many of its rooms had been turned into hospital wards.

Citizen Nicholas Romanov and his daughters Olga, Anastasia and Tatiana. Tobolsk, winter of 1917-1918

Public domainAfter the Revolution of 1917 and Nicholas’s abdication, Nicholas and his family (including Anastasia) were taken as prisoners to Tobolsk, then to Yekaterinburg, where on June 18, 1918, Anastasia celebrated her last birthday.

Porosenkov log, the place where the bodies were eventually discovered.

Semekhin Anatoly/TASSAnastasia and her family were shot on the morning of July 17, 1918. Their bodies were taken to the Four Brothers mine near the village of Koptyaki, 10 miles north of Yekaterinburg. There, the bodies were burned with sulfuric acid, so they couldn’t be identified, and thrown into the Ganina Yama (Ganin Pit). The next night, Yakov Yurovsky, the principal man in charge of the execution, and his aides returned to the site to move some of the bodies to another place. This was done in order to confuse any search for the royal family’s remains – the body count wouldn’t fit.

The Porosenkov Ravine. The gravesite of Nicholas II, his family, and servants on Koptyaki Road beneath boles and railroad ties.

Public domainThe remains of Nicholas, Alexandra, and their three daughters were first discovered in 1979 in Porosyonkov log (Piglet Ravine), four and a half miles from Ganina Yama, but kept secret until the USSR collapsed. Further investigations in 1991 showed that the remains of Tsarevich Alexey and a girl (Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna) were missing from the site. In 2007, they were discovered in another pit near the Porosyonkov log. In 2008, genetic expertise proved the newly found remains to be those of Alexey and Maria. Further research in 2019 conducted by the Investigative Committee of Russia confirmed the results. They were also approved by a disinterested party – Michael Coble of the Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory in Rockville, Maryland.

Anna Anderson in 1920

Public domainThe rumors about Anastasia somehow managing to escape the shooting of the tsar’s family and survive appeared immediately after 1918 in European circles of Russian emigres. In 1920 in Berlin, a young woman was stopped by a policeman from jumping off a bridge. The woman was apparently in a state of a mental breakdown and was sent to a mental institution in Dalldorf (now Wittenau, in Reinickendorf). Within two years she was telling people that she was Grand Duchess Anastasia. You can read more about Anna Anderson and another Anastasia’s impostor here in our article.

READ MORE:5 popular films about Anastasia Romanov

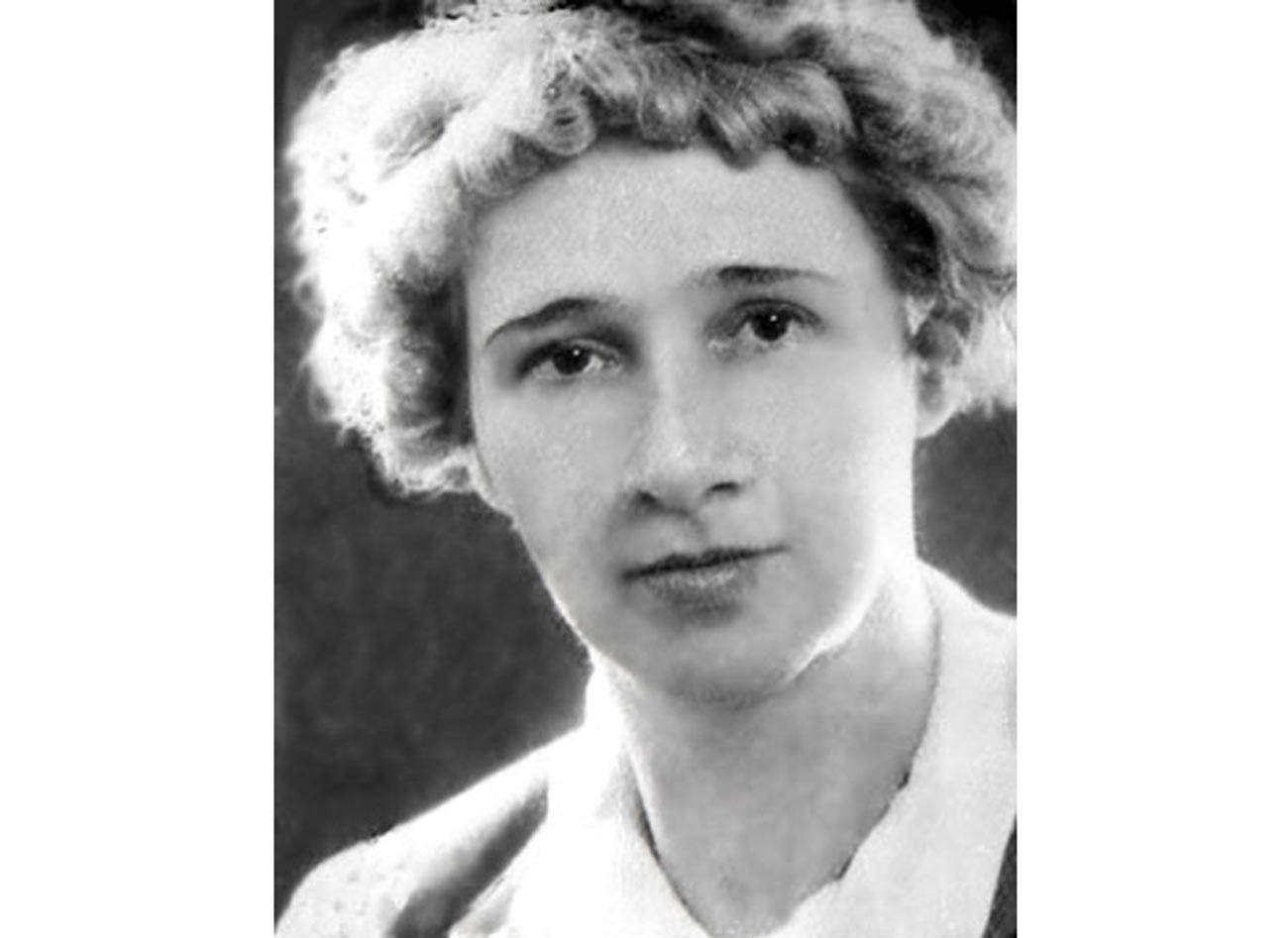

Eleonora Krueger

Public domainOther famous fake Anastasias include: Eleonora Krueger (1901-1954), who posed as the Grand Duchess in a Bulgarian village; Nadezhda Vasilyeva (?-1971), a mentally ill woman who spent years in mental institutions and prisons in the USSR and eventually starved herself to death in a prison psychiatric hospital on Sviyazhsk island, now Tatarstan, Russia; Natalya Belikhodze, a Georgian woman who “revealed” herself to be Anastasia Romanov in 1995. She died in 2000 and was considered to be the last fake Anastasia.

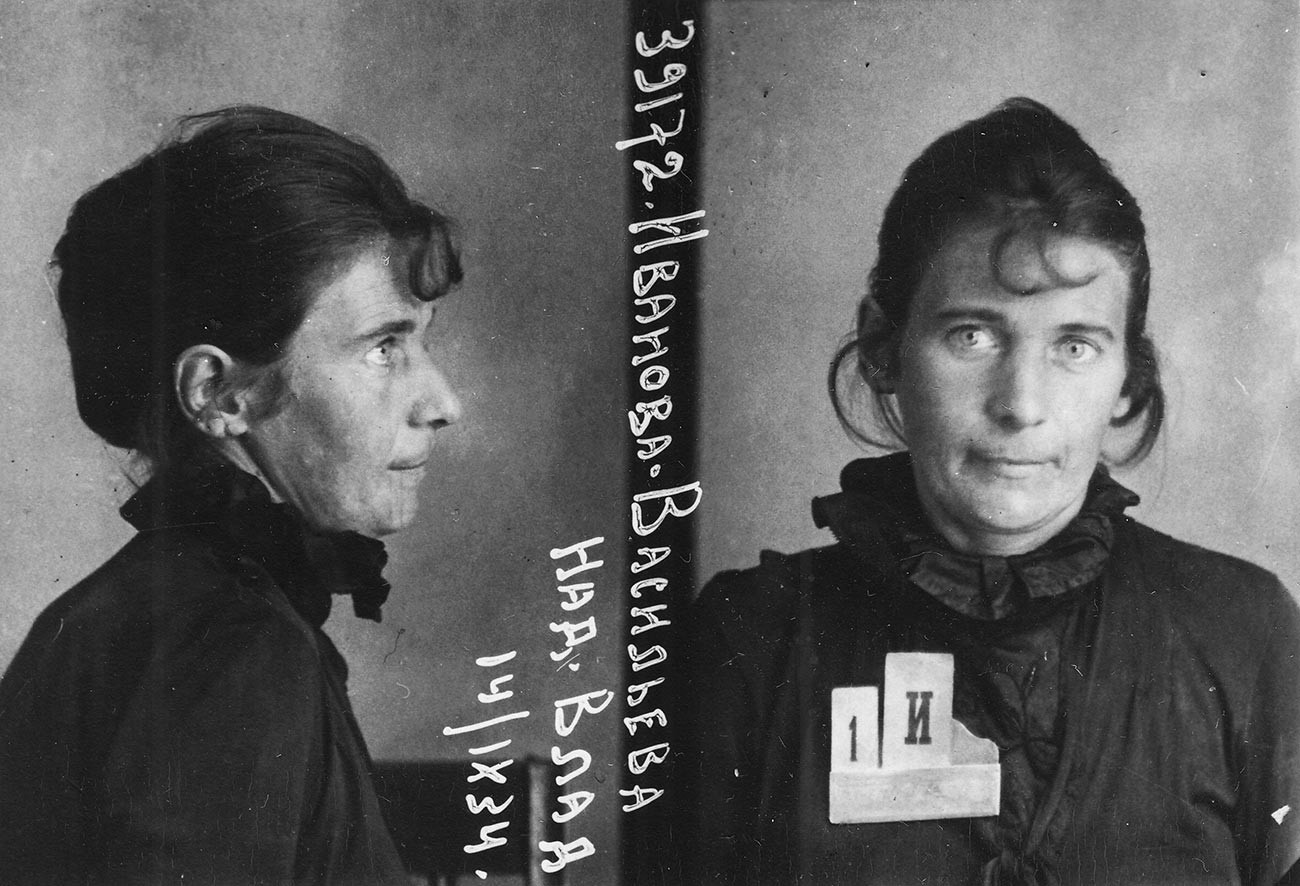

Nadezhda Ivanova-Vasilyeva

NKVD ArchiveIn total, there were over 30 of them. One Russian guy, Anatoly Ionov (b. 1936), even claimed he was Anastasia’s son!

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox