‘The Tale of Bygone Years,’ Russia’s medieval Primary Chronicle, describes in detail the baptism of the Rus by Grand Prince Vladimir (960 – 1015), and how he chose the Greek Orthodox faith over Islam, Judaism, and Roman Catholicism. Surprisingly, the Greek chronicles didn’t mention the Baptism of Rus’ of 988, performed by Vladimir the Great. In fact, there are no historical Russian sources to support or deny the version of events stated in the Tale of Bygone Years.

One of the foremost Russian historians of the epoch, professor Vladimir Petrukhin, notes that “not only is the exact time of the baptism [of Grand Prince Vladimir] unknown, but also the place of the baptism. The silence of the Byzantine sources about the baptism of the Russian land also looks strange.”

So, what do we know? And why did the Byzantines prefer not to mention Vladimir’s baptism? There could be several reasons for that.

Photios I of Constantinople

Public domainIn 860, Russians attacked Constantinople. About 8000 troops on 200 ships appeared seemingly out of nowhere on the Black Sea shore, plundered the city’s surroundings, but probably failed to conquer it and left, nevertheless taking with them a huge loot and leaving fear behind. The Papal seat referred to the attack as “the Lord's punishment for the sins of Constantinople’s citizens.”

Photios I (c. 820-893), Patriarch of Constantinople, sent word to Rome that he sent missionaries to Russian lands to propagate Christianity and baptise the pagan Russians. By baptizing the ruling elite, Byzantium sought to consolidate the pagan states in its sphere of influence and reduce the risk of military conflict on its borders.

However, Photios I didn’t specify the place nor the time of the baptism. Some sources state that the Kievan princes Askold and Dir were baptized with some boyars and a certain number of people. If this happened, then it explains why the Baptism of 988 wasn’t mentioned in Byzantine sources – Russians were already perceived as Christians by that time. However, no traces of Christianity in Kievan Rus’ of the 800s were discovered. They appear in the 10th century, when Princess Olga was baptised.

"Baptism of Olga" by Sergei Kirillov

Sergei Kirillov (CC BY-SA 3.0)In the 940s, Prince Igor (878-945), son of Rurik, again attacked the borders of Byzantium – not very successfully, though. In 944, a peace treaty was made, and what is significant is that by that time, there were so many Christians among the Russian warriors that they said their peace vows in a church in Constantinople, separately from the pagans, who kneeled before an image of pagan god Perun.

The first Russian ruler to be officially baptized in Christianity was Princess Olga (920-969), Prince Igor’s widow. Historians debate, however, when and how exactly it was done. Most agree that Olga was baptized in Constantinople in 957 by Romanos II (938-963), son of Emperor Constantine VII.

But this baptism was also based on political interests. Byzantium needed the Russian warriors to help them fight the Arabian rulers of Crete. In exchange for this help, Olga agreed to adopt Christianity and wanted Byzanitum to acknowledge Kievan Rus’ as a separate and independent Christian state. Sources claim that around this time, in the late 950s, she also sent envoys to Holy Roman Emperor Otto I, asking him to send priests and clergy to establish Christianity in Kievan Rus’.

Ancient Russian body crosses

Archive photoSo, Olga played on the rivalry of the Holy Roman Empire and Byzantium. Constantine VII, probably upon learning about Olga’s embassy to the German lands, agreed to meet her demands, and the following year, in 960, a Russian army was sent to Crete, while the German embassy was sent away.

Meanwhile, in the 10th century, Christianity was already known and practiced in the Russian lands. Archaeological findings include body crosses, Byzantine coins with Christian symbols worn as body icons, and other artefacts.

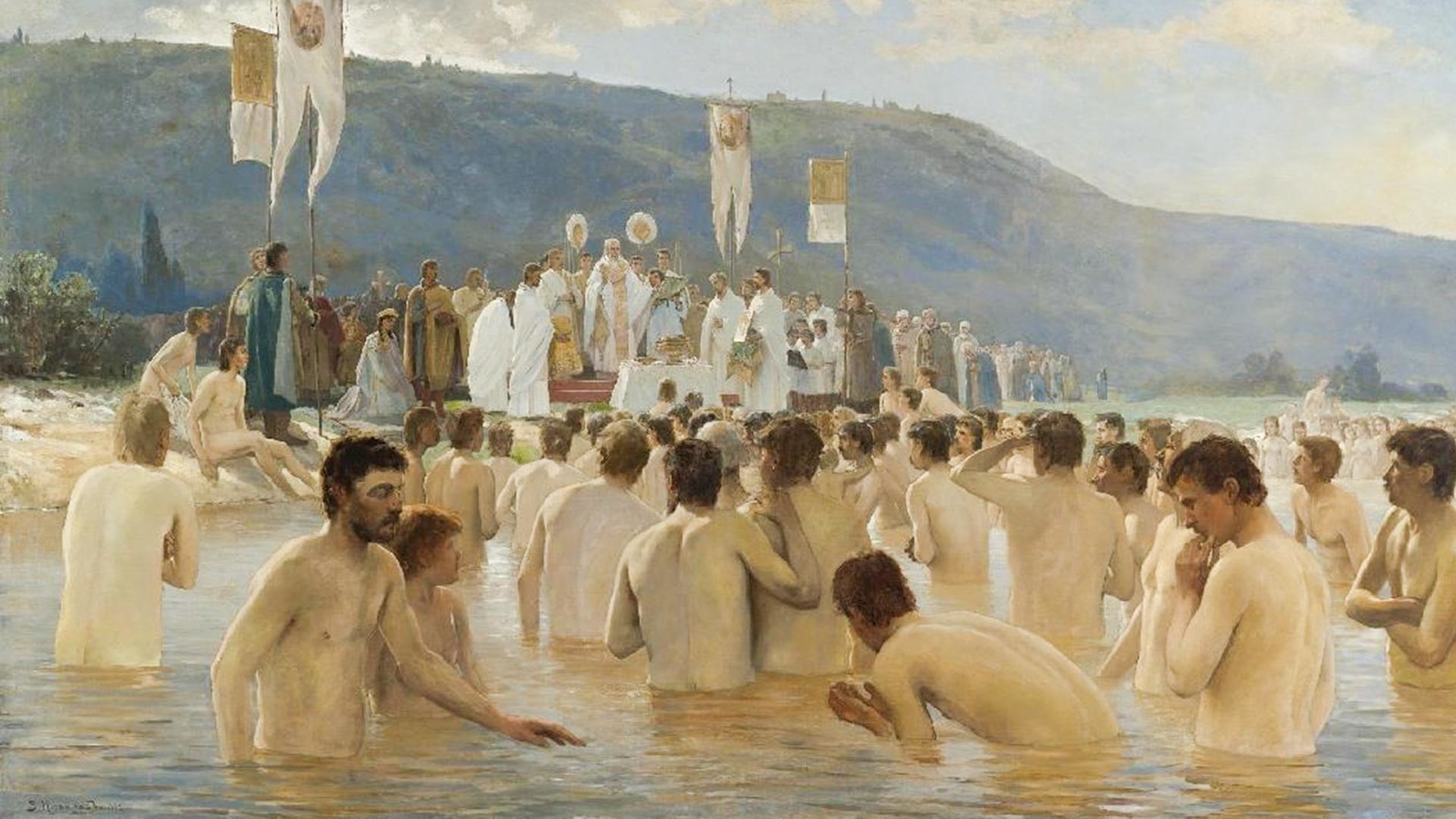

"Baptism of Russians" by Vasiliy Navozov

Vasiliy NavozovPrince Vladimir was Princess Olga’s grandson. His father, Prince Sviatoslav (943-972) didn’t want to be baptized – he was reported as saying that his peers would “mock” him. Prince Sviatoslav led campaigns against the Byzantine Empire, and was eventually killed. With such a strong neighbor as Byzantium, Russians had no choice but to cooperate or lose, really. Many Russians baptized into Eastern Orthodox Christianity to serve, work and live in the Greek lands.

Vladimir, who wasn’t born a Christian, initially practiced Slavic paganism as his religion. But pagans were by then already perceived as ‘uncivilized.’ When in 986, Vladimir signed a peace treaty with the Muslim state of Volga Bulgaria (located in the territory of the present-day Republic of Tatarstan, Russia), Volga Bulgarian envoys argued the treaty could not be equal because Vladimir “didn’t know the Scriptures” – indeed, paganism was a religion that didn’t use writing.

It is reported that, in 986, Volga Bulgarians sent their Islamic priests to Kiev to try to convert Vladimir and his closest circle to Islam. Supposedly, Vladimir also received missionaries from Otto I, but eventually, his choice was predestined by history: having had tight military and trade ties with the Byzantine Empire, Vladimir chose the Greek Orthodox faith.

However, in exchange for the baptism of Russia, Vladimir demanded the hand of Anna Porphyrogenita (963-1011), the daughter of Byzantine Emperor Romanos II (who baptised Olga). A pagan Prince marrying the Emperor’s daughter meant the Byzantine Empire acknowledged Vladimir as equal. The Emperor was reluctant to agree.

At the time, Constantinople was trying to suppress the revolt of general Bardas Phokas the Younger (940-989) and needed the Russian army’s help. In the middle of the conflict, Vladimir took Chersonesus, a Byzantine colony in the Crimea, and threatened to attack Constantinople. Under these conditions, the Emperor agreed on the marriage, and Vladimir begane the Christianization of Rus’. Russians then left Chersonesus, returning it to the Byzantine Empire.

What was important about Anna marrying the Russian prince is that, with her, priests and clergy came to Kiev – and the establishment of a new Orthodox church needed to be carried out by ordained priests. The process of the Christianization of the Russian lands wasn’t easy – not so much because pagan believers resisted conversion, but because the free pagan lands didn’t want to submit to Kievan rule.

By the 12th century, most Russian lands practiced Christianity. Especially important in this context was the spread of Cyrillic writing and literary tradition: it was after the baptism of Russia that the first monuments of ancient Russian written culture appeared. This was followed by other cultural shifts – from the introduction of Christian feasts (and fasts) to a gradual change in burial traditions - among them the pagan practice of cremation, which was replaced by inhumation (placing bodies into the ground).

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox