Those who received the status of His Imperial Majesty’s Court Supplier could forget about all their worries for a while. Supplying royalty with goods and services was quite profitable: some historians claim that significant sums of money were allocated for such purchases and, if successful, this partnership became stable and lasted many years. However, even for those suppliers whose contracts didn’t bring much money, it was worth their while: brands granted this title were considered “the best of the best” and received the right to put the state coat of arms on their packaging, signs, business cards and advertisements. There were also imperial court suppliers who supplied the members of the royal family.

But, as much as the title of the Supplier was desired, as hard it was to earn. For this, a tradesman or a craftsman should have met a range of strict requirements. First of all, they had to supply their produce or work for the imperial family continuously for 8-10 years. If there were any complaints about the quality of goods or services, the partnership could be terminated. Once, ‘F. Meltzer & Co.’ trading house, furnishing rooms in the Anichkov Palace, made a fatal mistake. They billed twice for the same project – and the emperor ordered not to hire Meltzer any longer.

The hard part was also that complying with all the requirements didn’t guarantee that one would keep this status. Since the title was often assigned to the head of the company, when owners changed – for example, due to the death of the previous owner – the long path to this title had to be taken anew. In such conditions, only truly remarkable people managed to receive the status of ‘Supplier’. And more than 20% of them, in 1910, were foreigners, including Germans.

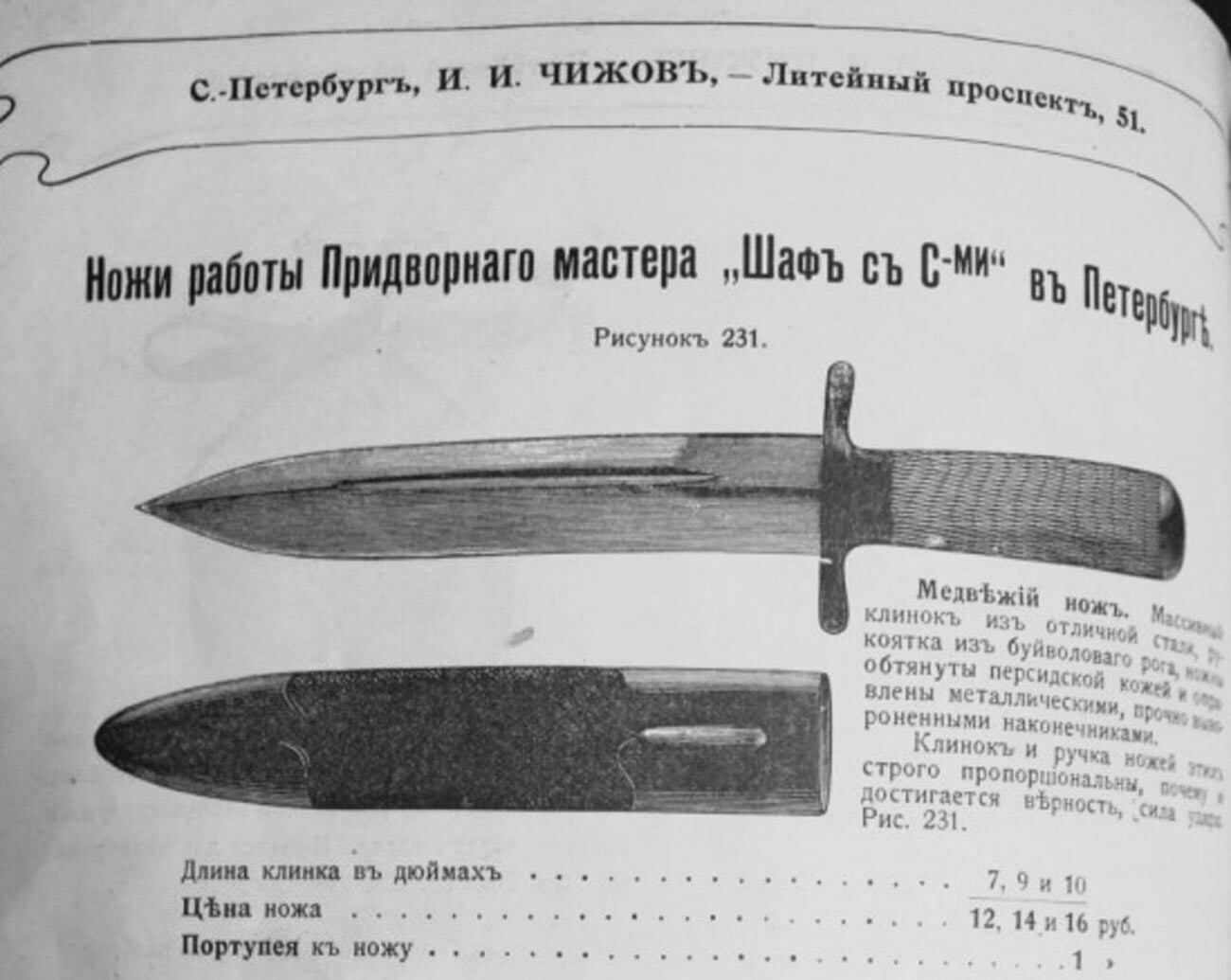

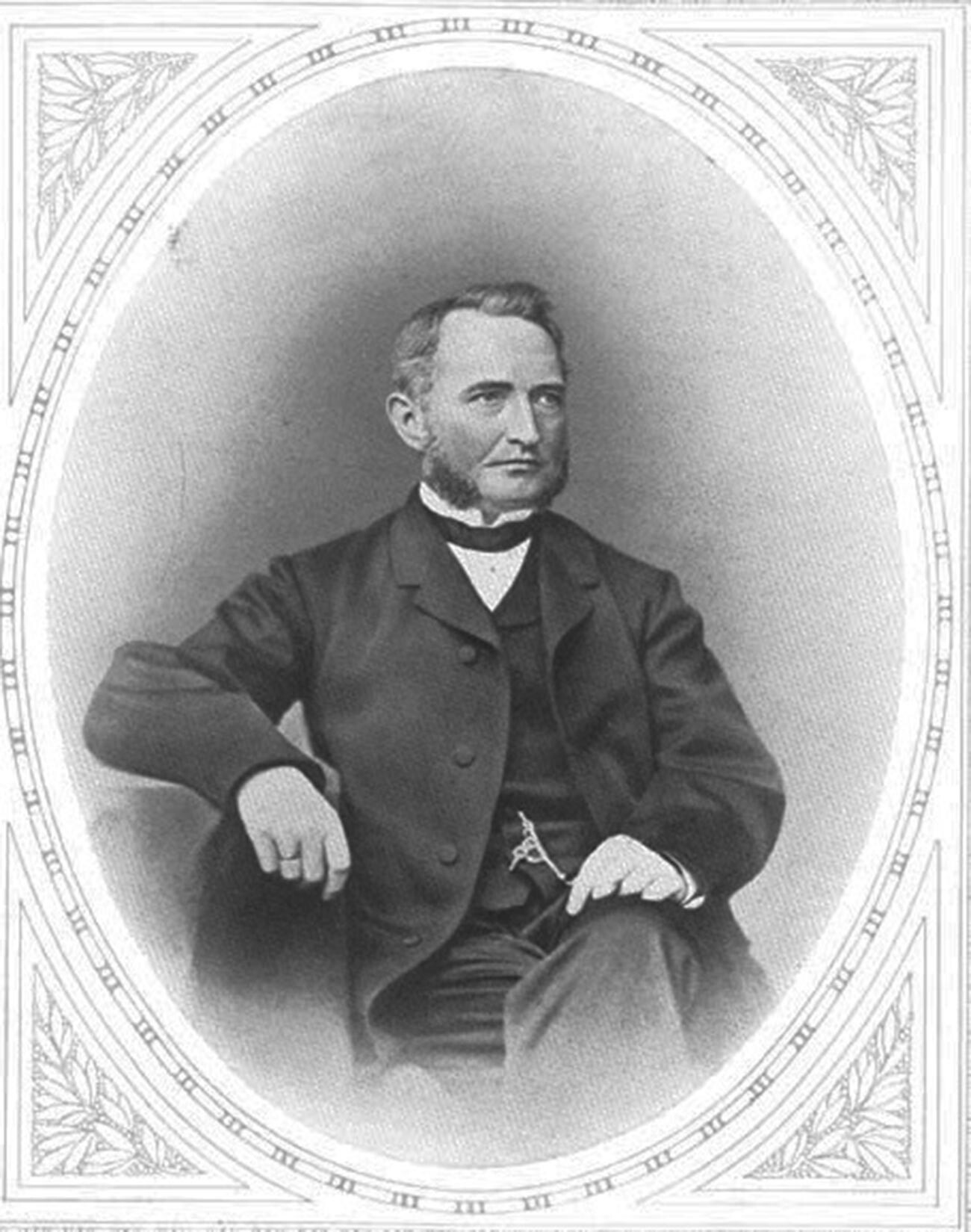

The Schaafs are a family of smiths, considered to originate from Wilhelm Nikolaus Schaaf, a master of manufacturing decorated blades from Solingen. At the beginning of the 19th century, Schaaf arrived in the Russian city of Zlatoust with his sons to pass his skills and knowledge in decorating blades with silver and gold images and inscriptions down to the local craftsmen.

After some time, he entrusted this weapons company to his students and moved to St. Petersburg, where he began to grow his own manufacturing. Producing mostly metal products and utensils at the beginning, by the middle of the 19th century, the family focused fully on cold weapons for officers. The Schaafs opened a workshop, a store and then a factory – presumably the largest privately owned factory specialized in cold weapons in Russia at that time. Schaafs’ blades were supplied to all Russian emperors from Alexander I to Nicholas II and are still preserved in Russian museums.

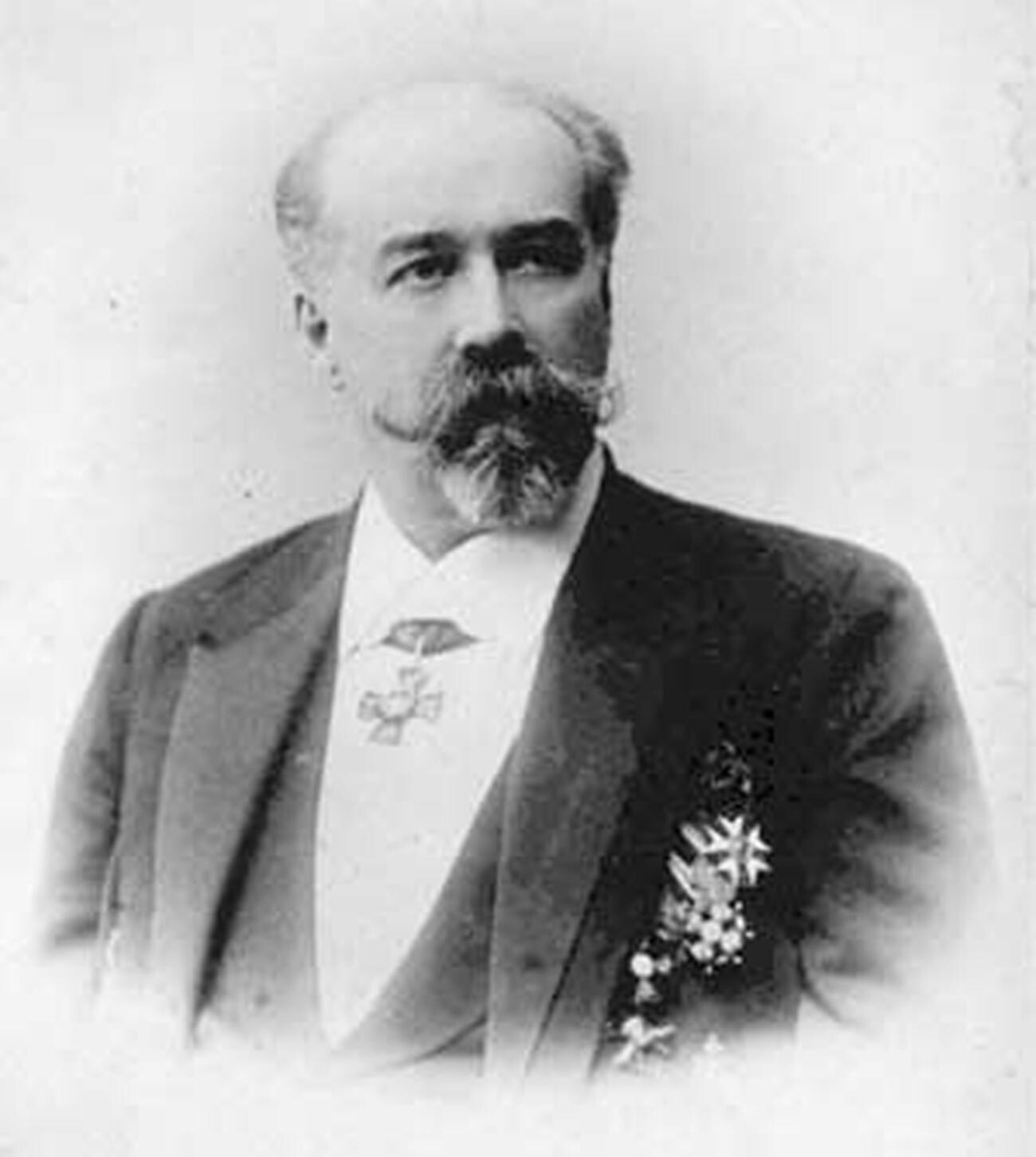

Ferdinand Theodor von Einem.

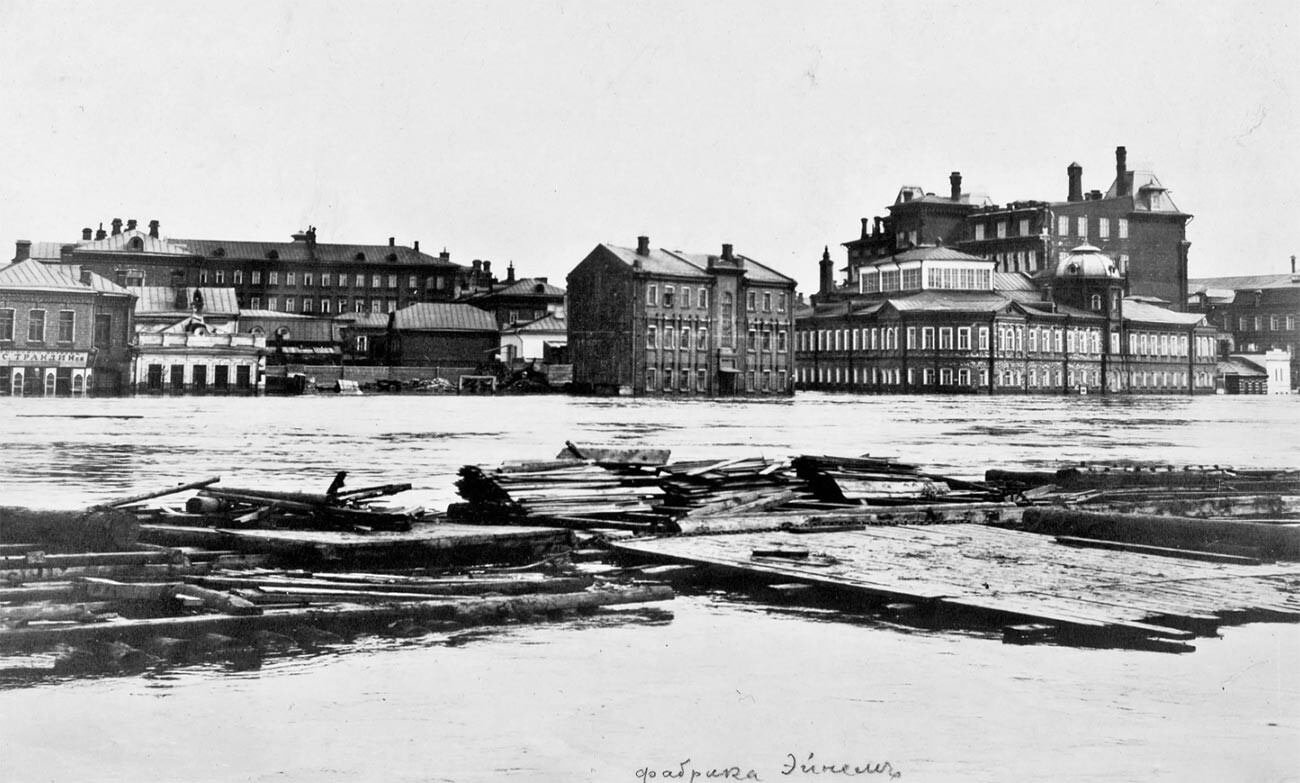

Public domainGerman Ferdinand Theodor von Einem arrived in Moscow at approximately 20 years of age, dreaming of opening confectionery production in the Russian Empire. Fyodor Karlovich (that’s what the entrepreneur called himself in the new country) began with a small company that produced candy and chocolate. As production grew, Einem found a companion – his compatriot, a young confectioner named Julius Ferdinand Heuss. Together, they opened a store in the middle of Moscow, as well as a three-story factory.

The manufacturer was famous for its wide assortment and its mind-bending advertisement: boxes with candy from Einem had postcards and musical notes in them, the packaging was decorated with paintings of famous painters and the name of the manufacturer was featured on the first zeppelins.

In 1882, participating in the large-scale All-Russia Industrial and Art Exhibition, Einem gave Empress Maria Feodorovna a gift never seen before – a flower bouquet made of candy. However, the company received the title of the Supplier only after the death of its founder, in 1913. The company was fully transferred to Julius Heuss, but kept its previous name.

“How many concerts of the past season were held without Becker’s pianos? If we’re not mistaken, all local and touring piano virtuosos performed during concerts with Becker’s pianos; indeed, in any even slightly relevant concert, where a piano was needed, almost certainly the piano on the stage was not someone’s but Becker’s,” newspaper ‘St. Petersburg Vedomosti’ wrote in 1855.

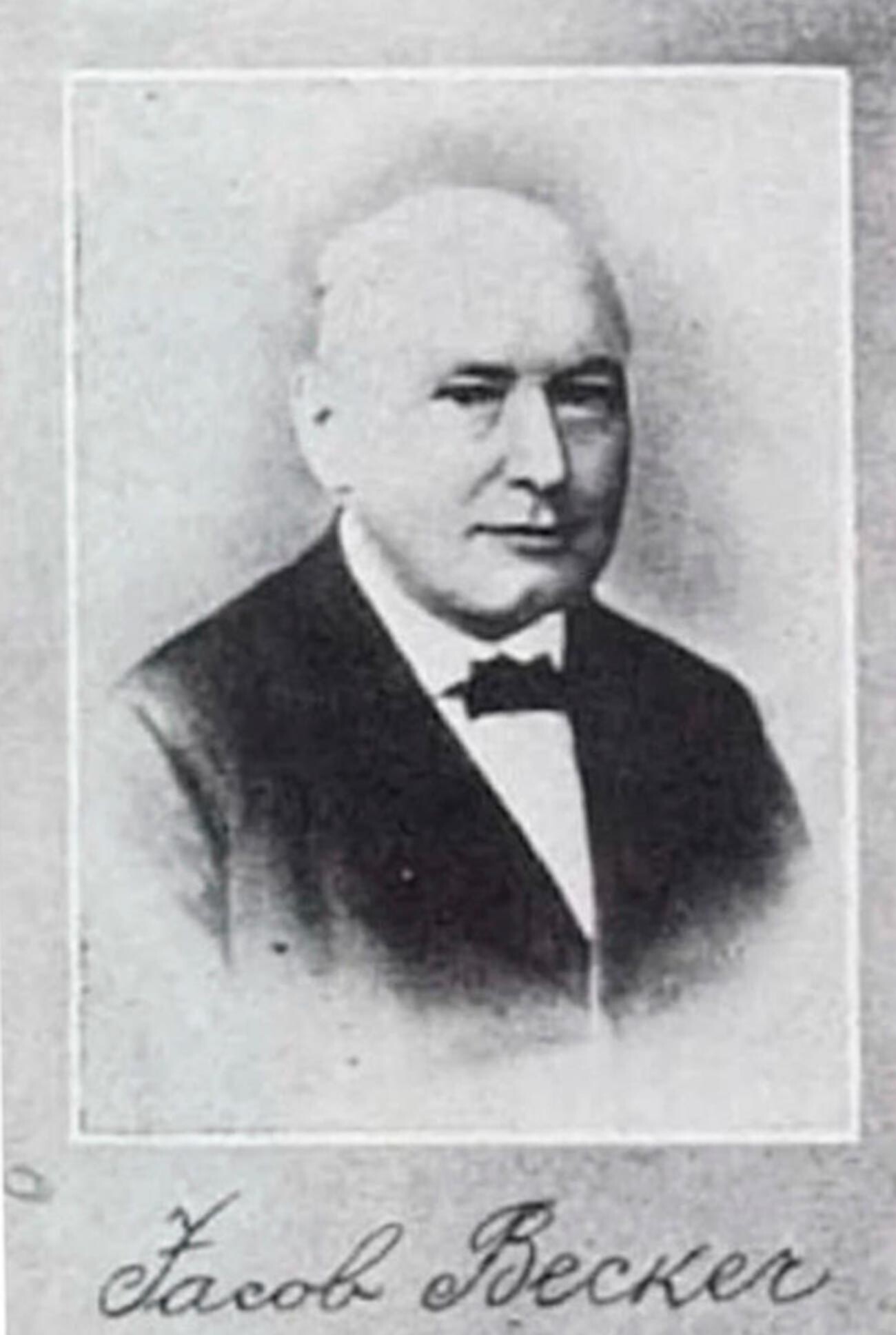

Jakob Becker.

Public domainKeyboard instruments by the Palatinate native, who opened first a small workshop and then a whole factory in St. Petersburg, were really enjoying great popularity – both in the Russian Empire and beyond. Not just a brilliant craftsman, but also a daring innovator, Jacob Davidovich Becker was the author of several improvements that ensured the highest quality of sound for his pianos.

Many famous pianists used Becker’s pianos: Franz Liszt, Anton and Nikolai Rubinstein, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Emil von Sauer, Alfred Grünfeld, Hans von Bülow, Sophie Menter and others. Anton Rubinstein even claimed that, in his 30 years of work in Russia, he only worked with Becker’s pianos. Among the famous clients of the company were also the highest persons: the Danish king, the Austrian emperor and, of course, the members of the Romanov family – the Emperor of Russia himself and Grand Dukes – Vladimir Alexandrovich, Konstantin Nikolaevich and Nicholas Nikolaevich.

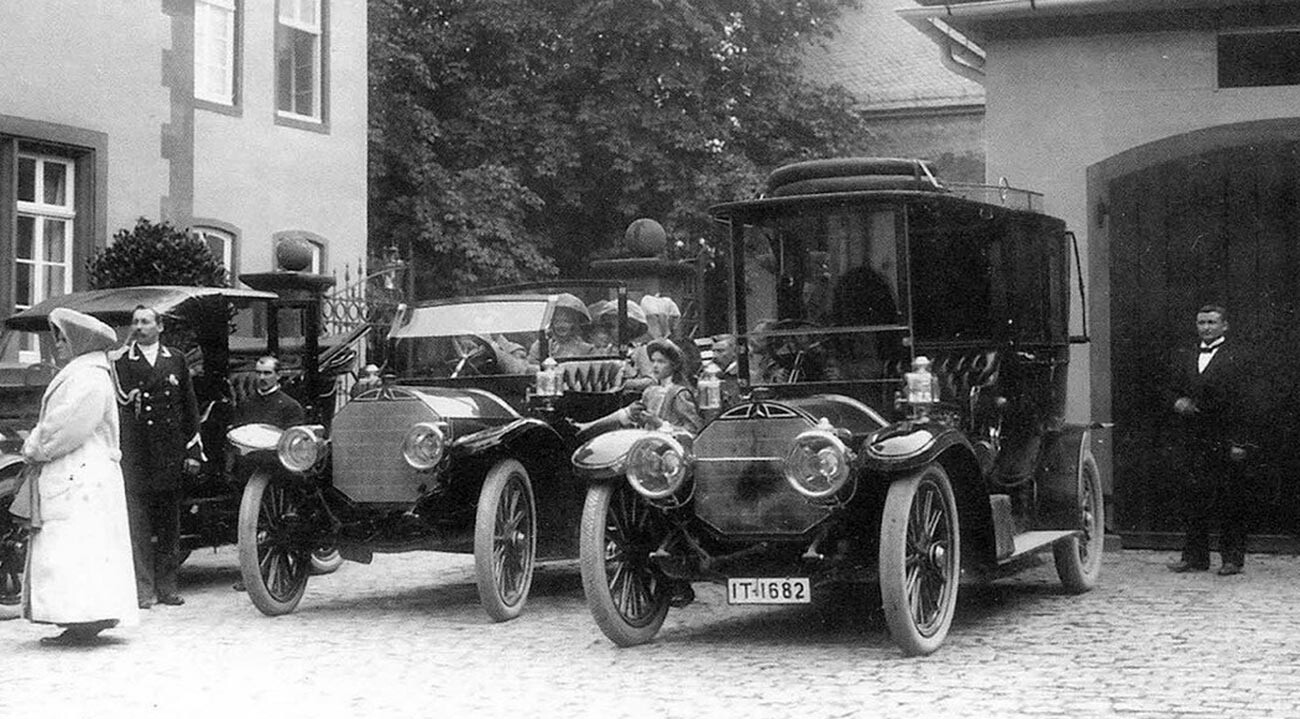

Once, visiting the relatives of his spouse in Darmstadt, Nicholas II had a ride in a car. Being a great horseback rider, he still didn’t regard the new means of transportation with particular excitement. However, after this ride, he visited Prince Vladimir Orlov many times and almost every day they took a car ride – until, one day, he decided to purchase several cars of his own.

In 1905, seven Mercedes cars, which, back then, were already famous for their speed, arrived in St. Petersburg for Nicholas II. From that moment on, the imperial garage was stocked mainly with German cars. Two of them – vans on the chassis of Mercedes trucks, loaded with picnic supplies – were presented to the monarch by German Emperor Wilhelm II himself. In 1912, ‘Daimler Motoren Gesellschaft’ became His Imperial Majesty’s Court Supplier. It’s not surprising: by spring of the following year, 11 out of the 29 cars in Nicholas II’s garage belonged to that brand.

Alexander Poehl.

Public domainThe building of the Poehl’s Pharmacy in St. Petersburg is to this day shrouded in mystical legends. People said its owners practiced alchemy and kept real griffins in the tower over their lab – in reality, however, the Germans were simply talented pharmacists and managers.

Wilhelm Poehl purchased the old pharmacy in the middle of the 19th century. He expanded and equipped the lab, organized a warehouse, introduced quality control of raw materials, founded the Russian society for selling pharmacy goods and began a partnership with the imperial court. His son, Alexander, inheriting the family business, continued the reforms begun by his father and turned the company into a whole industrial complex. He, for example, invented the only medicine that was exported from Russia at that time – Sperminum-Poehl. The Poehls were one of the first in the country to sell medicine in ampules, tablets and dissolving capsules. Their assortment also had completely unique wares – for example, gilded tablets for the wealthiest clients.

Companies that sold orchard saplings from European plant nurseries were rapidly developing in the 19th century in Odessa. Not only the availability of sea shipping, but also a large amount of dachas and manors on the Black Sea shore granted such companies great success. Gardens and parks of southern estates required plants, including roses that the owners of local dachas planted after the example of the Russian empresses.

The main Odessa supplier of roses was Bavarian Emil Georgievich Werckmeister. By 1904, the assortment of his nursery, founded in 1867, had about 900 varieties of this flower. Werckmeister’s roses received many of the highest awards at different exhibitions and the researchers of the entrepreneur’s biography note his contribution to the restoration of the ‘Alley of Roses’ in the imperial estate of Massandra.

“So many future blossoming plants fit into this one room in a wooden closet with small narrow drawers that they could turn our entire Black Sea region into Eden,” is how Soviet author Valentin Kataev, who was born in Odessa, remembered Werckmeister’s nursery.

Ferdinand Krauskopf.

Public domain“Best galoshes in the world!” The advertisement signs of T.R.A.R.M. - Russian-American Association of Rubber Manufactory – said. This company and its founder, Ferdinand Krauskopf, launched rubber production in Russia, realizing the giant potential of the local market. Before that, Krauskopf was selling American galoshes in Hamburg, so he knew well how to develop such a company. Having found some companions, the German built a factory in St. Petersburg, equipping it with the latest technology.

To his clients, Krauskopf offered waterproof clothing and galoshes that could save expensive leather footwear from water, while to industrialists – industrial belts, pipes for gas pipelines, pump valves and other products. The company marked its products with a triangle – a sign understandable even for an illiterate buyer – and consequently changed its name to ‘Triangle’.

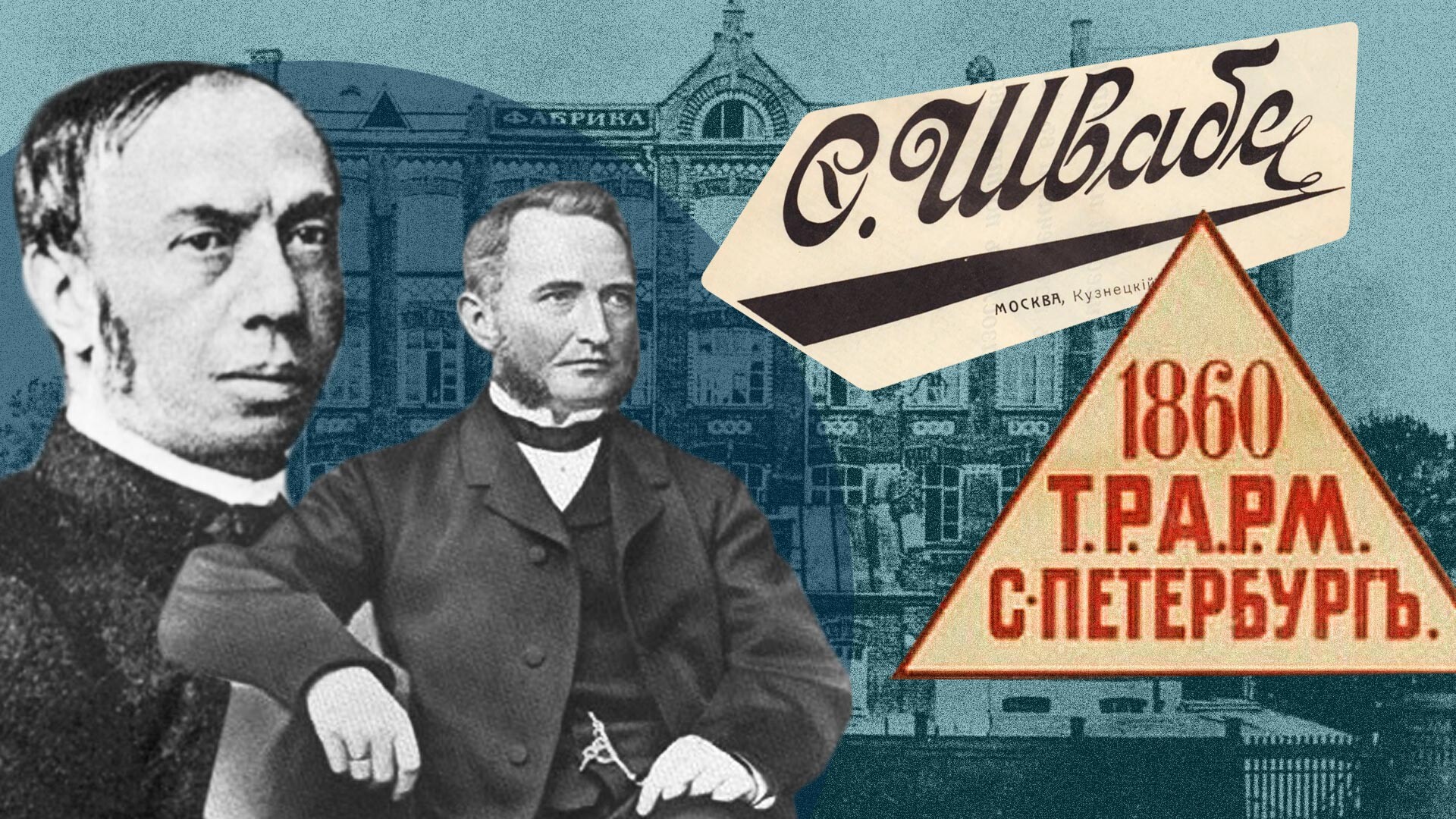

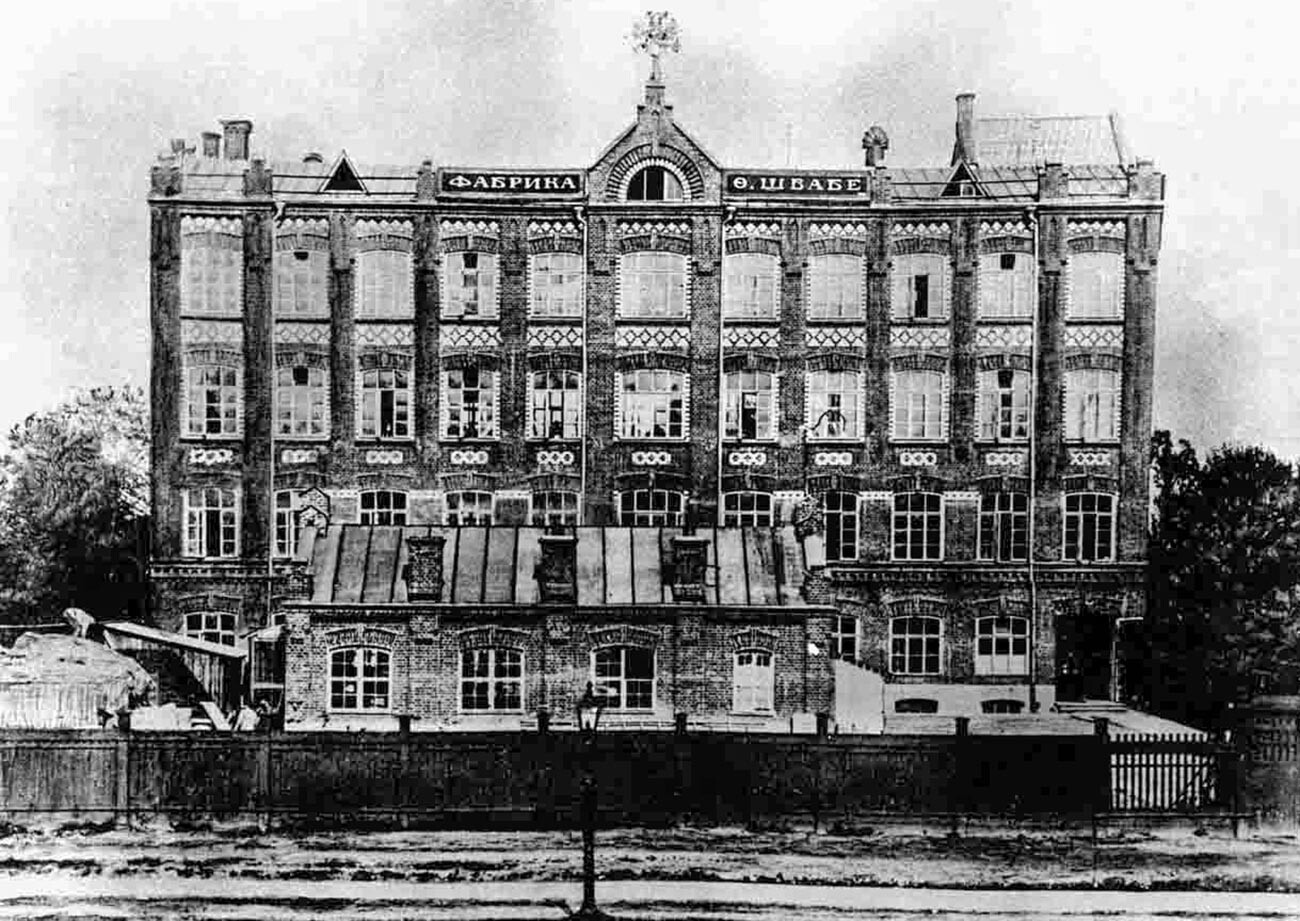

One of the largest companies in Russia in the 20th century in manufacturing optical, physical and geodetic instruments started from a small store where German (according to other sources he was Swiss) Theodor Schwabe was selling glasses and pince-nez.

Theodor Schwabe.

Public domainSuccess came to the merchant by widening his assortment and participating in exhibitions where Schwabe’s company earned prestigious awards multiple times. The emperor also favored the foreigner: back in 1854, Schwabe presented Nicholas I a model of a cannon; the monarch was so delighted with it that he gifted the craftsman a diamond ring with a ruby.

The second face of the company was the nephew of owner David Albert Hamburger. Entering the company as a regular employee, he became a partner over time and then, after Schwabe left – the sole head of the company. He developed the enterprise in the Russian regions, significantly expanded the staff and earned the title of His Imperial Majesty’s Court Supplier. One could buy all sorts of instruments and equipment at F. Schwabe – from binoculars and barometers to medical corsets and x-ray machines.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox