In the 1990s, journalists described Valentina Solovyeva as Russia's richest woman. This "psychopathic individual with an exaggerated sense of self-worth" (according to an expert medical evaluation) cheated the whole country for several years. She kept the money - millions of dollars - in black briefcases at home. Huge deposits against promises of gigantic interest rates were brought to her by Russian stars, owners of banks and factories, and government officials. In her confident voice, she claimed that she would double any amount in a month.

And when the pyramid collapsed, it emerged that everyone had been taken advantage of by a former hairdresser's cashier in Moscow Region, who had not even finished high school. How was it possible? Not everyone understands it even today.

To begin with, on becoming an entrepreneur, Solovyeva came up with a beautiful legend about herself: She was born in a nomad camp, her mother was a Roma and her father a Russian officer. It is not entirely clear why it was necessary, but the future fraudster must have wanted to romanticize her image. In actual fact, she was born on Sakhalin Island (6,400 km east of Moscow) in 1951 and dropped out of school without finishing ninth grade. With her first husband, she moved to the town of Ivanteyevka near Moscow at the end of the 1980s, and for a time worked as a cashier at a hairdresser's.

Then, Valentina got married a second time, and, together with her husband, opened the firm Dozator. It traded in goods that were in short supply, in other words, anything and everything. And already a year later, in 1992, she set up her own private enterprise called Vlastilina. A bank gave her a loan of 1.5 billion non-denominated rubles (equivalent to 1.5 million rubles or $23,000 today) for the construction of cottages, while she continued to trade furniture, chandeliers, refrigerators and cars.

Solovyeva and her second husband

Russia 1/youtube.comVery low, non-market prices were the main feature of all her businesses. For example, she would sell a car worth eight million rubles for just 3.5 million. There was just one condition for the sale: The money for the purchase was to be paid in full a month before receipt of the goods. And, indeed, in the first year, Vlastilina sold 16,000 Moskvitch and Zhiguli cars (the whole of the police directorate for economic crimes drove these cars, among others). So people began to trust her.

Deposits were another item of income. Solovyeva accepted deposits with the lure of enormous interest: 50 percent (in two weeks) and 100 percent (in a month). In order not to embarrass her investors, she called her firm a bank, although she had never held a banking licence. True, she was not put on any blacklist either, because she had tax inspectors and police officers.

"Vlastilina never did any advertising. What would have been the point? Even the banks which gave me my first loans started bringing their money to me, taking back twice as much," says Solovyeva.

When there were too many people who wanted to deposit their money with her, she introduced a threshold for entry - 100 million rubles (equivalent to 100,000 rubles or $1,500 today). Now her client base included only wealthy people. Among her investors were "Russian Madonna" Alla Pugacheva, king of Russian pop music Filipp Kirkorov, and many others.

Of course, Vlastilina did not perform any miracles and operated just like any other financial pyramid scheme: part of the money from new investors was used to pay the previous ones, and another portion of the money was invested in enterprises and stocks or went into her own pocket. The times, too, played into her hands. "Inflation was enormous. If today, you don't have time to buy dollars, tomorrow your money will turn into candy wrappers. What she needed to implement her scheme was a rising trend. It was the nature of the times," said Aleksey Muskatin, who at the time was the manager of a well-known pop singer, and who introduced Solovyeva to the creme-de-la-creme of Russian show business.

Problems started in 1994, when Vlastilina began to delay payments for a long time. The prosecutor's office opened a case relating to charges of fraud on a particularly large scale. But even then, people continued to believe in the pyramid. On the last day of Vlastilina's existence, Pugacheva herself handed over $1.75 million to the fraudster. The pop singer had hoped to double her capital.

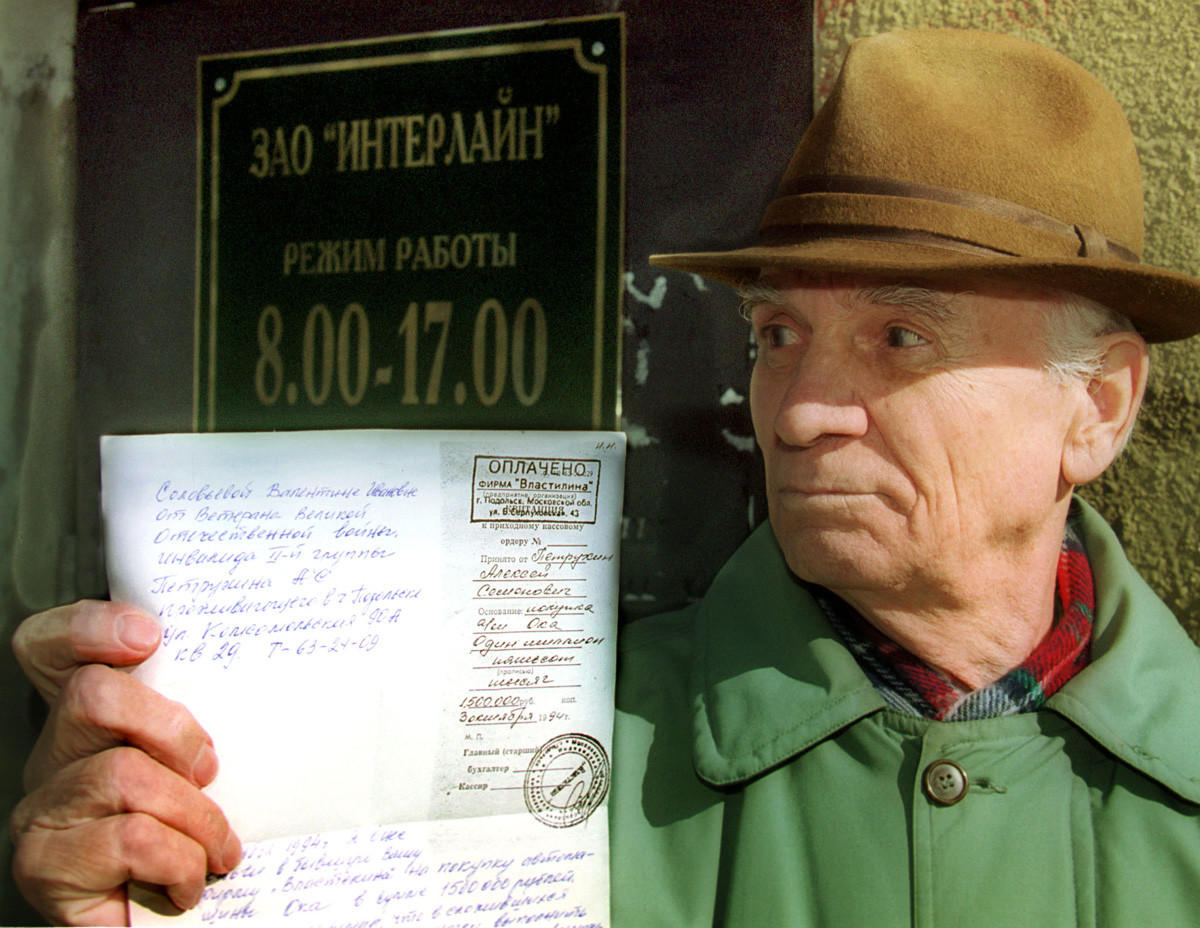

The trial of Vlastilina’s founder of took five years. There were about 500 volumes relating to the criminal case, and 16,600 victims were involved. According to the official investigation, she had collected 692 billion non-denominated rubles (the equivalent of $10.6 million today) but returned only 189 billion rubles or $2.9 million to investors (admittedly, she claims that even more money - trillions - passed through her hands).

Solovyeva attended the court hearings in diamonds and furs, made speeches as if she was an actor in the theater and would not admit her guilt. She was sentenced to seven years in prison, four of which she had already served under investigation. She was allowed no visitors or parcels. But she ended up only serving two years and was then released on parole.

While she was in prison, her father and husband both died. Her father never recovered from a stroke he had when he saw his daughter behind bars in the courtroom on television. And her husband hung himself. However, Solovyeva believes that her husband was murdered, because someone thought he knew where she had hidden the money. But, to this day, her billions have never been found…

These days, the former billionaire goes round Russian talk shows and proudly talks about her entrepreneurial past. She still doesn't consider herself guilty and believes she had simply been set up. "Well, didn't they have a brain of their own, bringing me all those millions? As soon as Vlastilina reached a certain level, an unspoken command went out to get rid of me. I was warned about it by people in very high places," she claimed on one such show.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox