For the first half of the Soviet Union’s existence, obesity was less of a concern than tackling hunger, malnutrition and related public health issues. However, once a sufficient supply of staple foods became available to everyone, a new problem arose in the 1970s. Many people who had spent most of their lives afraid of going hungry lacked self-restraint when faced with as much food as they wanted and began packing on weight. In the Soviet Union, being slightly overweight was not regarded as something shameful, but rather was seen as a sign of good health and stamina. Most famous actors and actresses were not particularly thin with just a few exceptions, such as Lyudmila Gurchenko or Lyubov Orlova. However, very soon the negative impacts of excessive weight became obvious: overweight people suffered from high blood pressure and were at higher risk for a whole raft of cardiovascular and metabolic issues. The Soviet state realized it was necessary to devise strategies for tackling obesity.

Tsentrsoyuz-Kislovodsk Health Resort. The kitchen.

Anatoliy Garanin/SputnikIn the USSR, people could purchase (or be allocated at a discount) a holiday voucher to state-run health resorts where they could not only take a break from work but also work on some of their health issues. Doctors at the resort prescribed them various medical procedures and a particular diet, including “Diet No. 8” in the case of obesity. These sanatoriums were not unlike present-day all-inclusive resorts, only instead of cake and pie, the selection included boiled fish and steamed omelets.

The system of medical diets for health resorts and hospitals was developed in the 1920s by the Soviet dietician Manuil Pevzner. In total, there were 15 types of diets that were used for various health problems, ranging from gastritis to diabetes. For overweight patients, the recommendation was to eat 5-6 times a day, avoid pastries, pasta, legumes, fatty meat and fish, sugar, honey, sweet fruits and lard. Cereals, seafood, greens, low-fat meat and rye bread were allowed. Broadly speaking, the advice was very close to contemporary recommendations for weight loss, and many Russian hospitals still use these set diets even today.

Moscow oblast. USSR. June, 1964. Patients of the Mtsyri tuberculosis prophylactic center Zoya Zanegina and Antonina Reusova drink koumiss during a treatment procedure.

Lev Porter/TASSMedical diets were only available at health resorts, and the ordinary Soviet family could not afford to eat so much high-quality meat and fresh vegetables. This is why their diet was based largely on carbohydrates from bread, pasta and cereals. Many people incorporated fasting days on which they only ate buckwheat or drank kefir, or refrained from any consuming any food whatsoever.

Over the past few years, intermittent fasting (skipping breakfast, fasting for 16-72 hours, etc.) has become a popular strategy for controlling weight and tackling an array of other health issues. In 2016, a Japanese cell biologist studying fasting’s impact on autophagy even won a Nobel Prize. But it turns out the benefits of intermittent fasting were widely known and applied in the USSR. One popular healthy lifestyle system was developed by Porfiry Ivanov, who lived in Rostov Region (in the south of Russia) from 1898-1983. His system was known as Detka (Russian for “baby”) and recommended, among other things, that you douse yourself with cold water every day, give up alcohol, eat less and fast for at least one day a week.

A hunger therapy clinic for overweight patients opened in Moscow in 1981 and was headed by Professor Yuri Nikolaev. Later, hunger therapy departments were set up at hospitals in other large cities too. The therapy consisted of fasting on various mineral waters and herbal infusions, with vegetables, fruits, dairy products, etc. gradually added to the diet. One mandatory element was long walks.

Even back the 1960s, Nikolaev was conducting research on the effects of fasting and diet therapy on people with mental health issues. He developed nutritional recommendations for a wide range of patients in his 1973 book Fasting for Health. He advocated moderation in food intake and advised people over 45 to fast a couple of days a month.

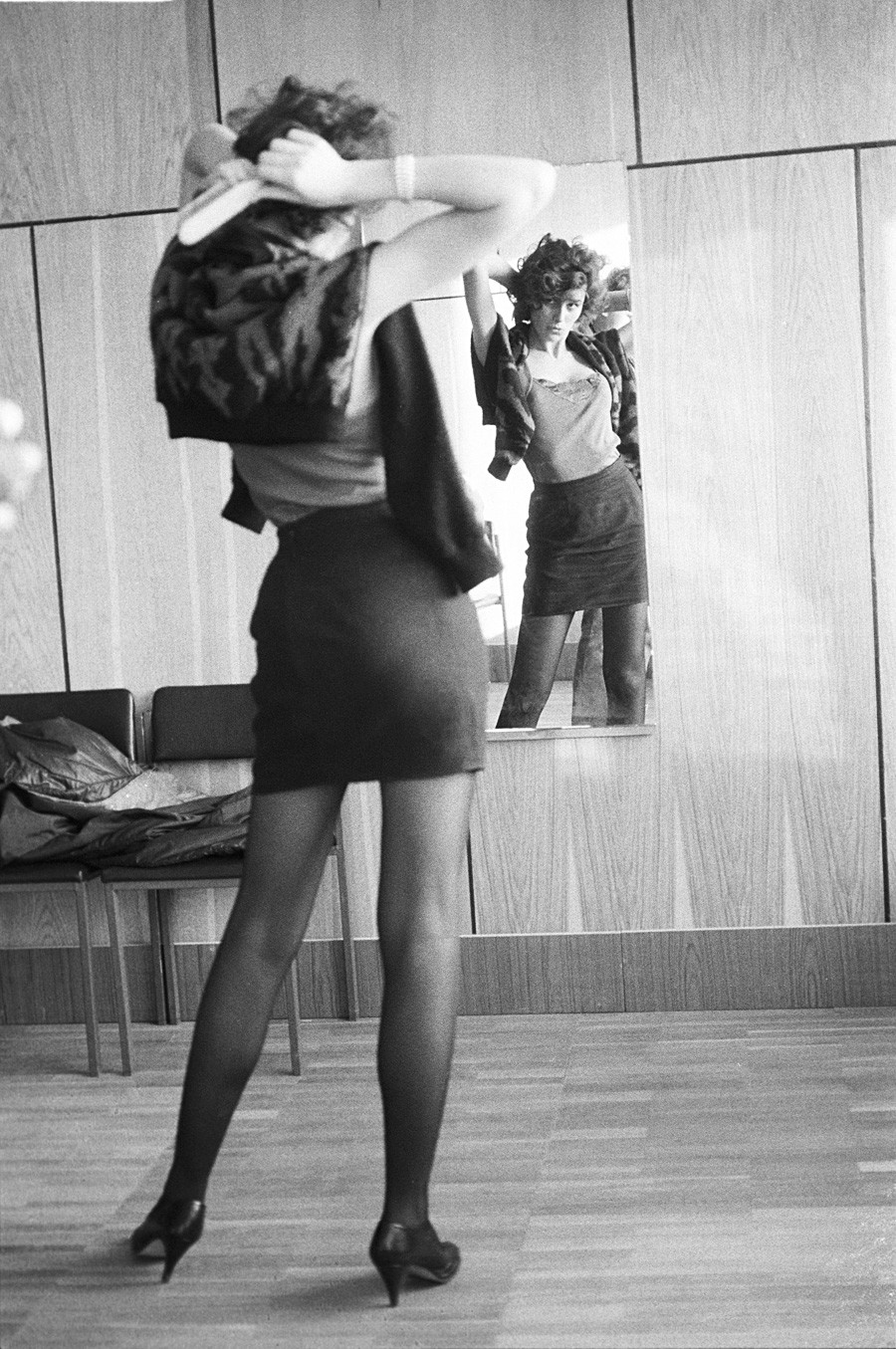

A participant in the Moscow Beauty 1988 pageant.

Igor Mikhalev/SputnikAnd yet, the majority of Soviet citizens opted for more traditional ways of trying to lose weight. Young women would copy diets from each other into their journals and exchange wonder recipes that promised to help them lose a couple of kilograms before some important occasion or other. One of the most common pieces of advice was to drink water-diluted vinegar after a meal and to replace dinner with kefir. Celebrities were another popular source for diet tips. For example, the famous actress and wit Faina Ranevskaya used to say that, "In order to stay thin, a woman must eat in front of a mirror, naked.” Meanwhile, the legendary ballerina Maya Plisetskaya's “secret” to having perfect figure was to "not stuff yourself."

In the 1970s, a points diet known as "the Kremlin Diet” came along. It dictated limiting daily carbohydrate intake to 40 points (with 1 gram of carbohydrates being 1 point), and it did not matter whether these came from bread or vegetables. On the plus side, sausage, mayonnaise and lard were allowed.

In the 1980s, the USSR went crazy for being slim. With the start of perestroika, foreign glossy magazines such as Burda Moden with its thin models made their way into the country. In 1988, Moscow hosted its first beauty pageant, and there was not a single plump figure among the contestants.

Holidaymakers at Snow Valley health resort.

B. Korobeinikov/SputnikThroughout its history, people in the Soviet Union were strongly encouraged to participate in sports. There were records with morning exercises on sale. Every organization had a "voluntary sports society" and different athletic groups, and during working hours there were mandatory breaks for physical exercises. Just about every household had an array of sports equipment, including weights, dumbbells, crossbars for pull-ups, wall bars, jump ropes, as well as skis, skates and rollers for outdoor activities.

The hula hoop was a particularly popular item among young girls. In the 1962 Soviet film Queen of the Gas Station, it was described as "a slimness device." With hula hooping, the recommendation was to exercise for at least 30 minutes a day, although not everyone had the patience for this. Another popular slimming gadget was a waist twisting disc, which required 20 minutes of exercise each day to produce any effect. The main thing was not to celebrate completing your daily exercise with a piece of cake, but of course that danger is and probably always will be relevant.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox