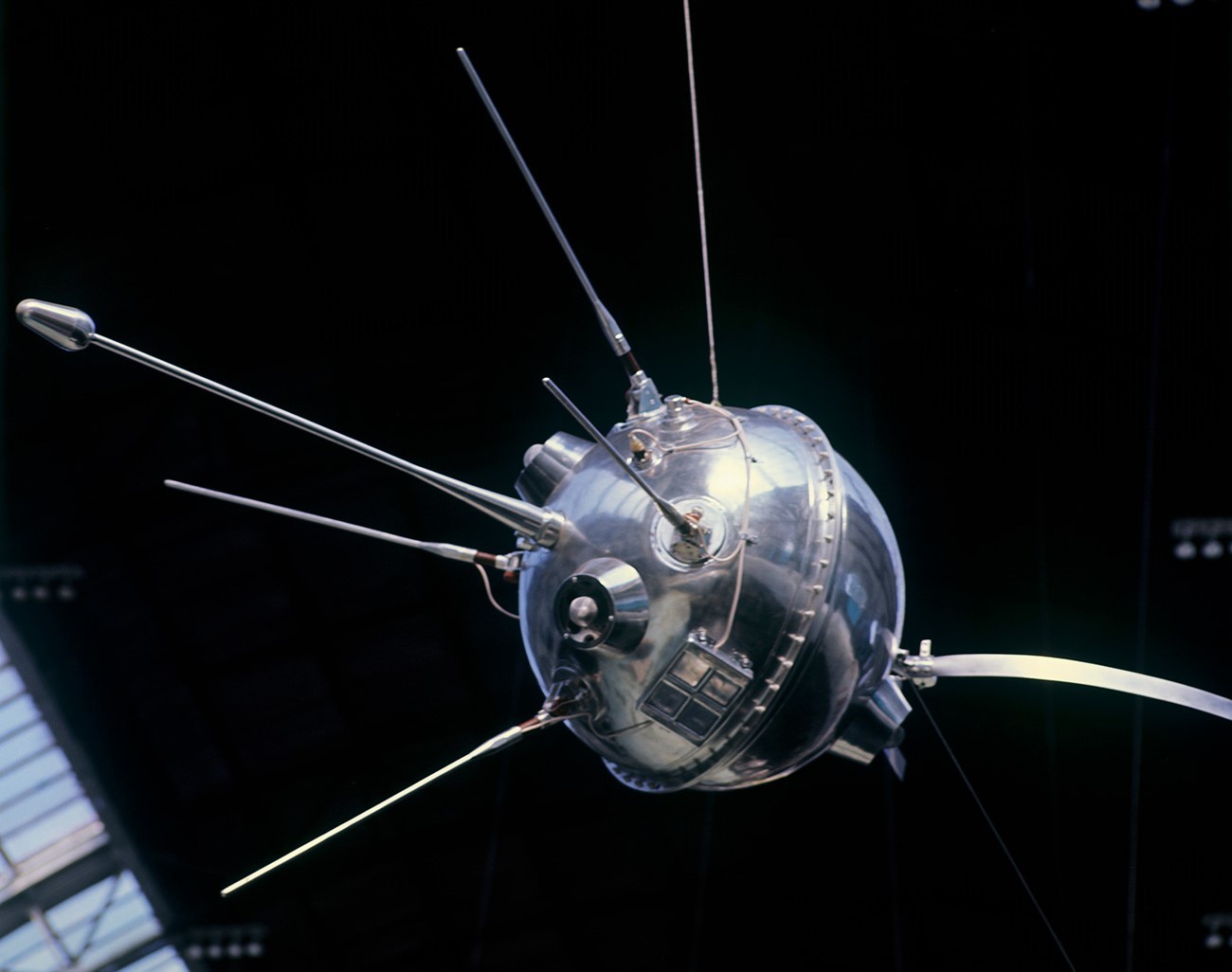

"Luna-16", an analogue of the station "Luna-15"

B. Borisov/SputnikYou might not know it, but Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins were not alone on the Moon. Their historic trip to Earth’s only natural satellite, however, eclipsed the Soviet Union’s epic failure. Even at the time, only those working on the project were aware of the true goals of the Soviet Luna-15 project. It was nothing less than a last-ditch attempt to steal a march in the space race.

The USSR had ambitious lunar landing and exploration plans. The country’s “Luna” space program – envisaging the launch of interplanetary spacecraft to the Moon – appeared in 1958, earlier than NASA’s Apollo program. Yuri Gagarin’s first manned space flight in 1961 only strengthened the Soviet belief that it was their destiny to dominate space. And for a while, it seemed they would.

At the fourth attempt, the USSR launched the Luna-1 station – the first spacecraft to escape Earth’s orbit (although it shot past the Moon). And in 1959, Luna-3 took the first photos of the dark side of the lunar surface. Other triumphant missions included the first man-made object to reach the Moon, and the first probe to make a soft landing on the surface.

Interplanetary Station "Luna-1"

Alexander Mokletsov/SputnikAs the name suggests, Luna-15 was the fifteenth officially announced mission (although in terms of actual launches it was the thirty-first). Many probes did not even get into Earth’s orbit, while others that did then refused to leave. In general, the Soviet government preferred to hush up failures, knowing that there was still a lot of work to be done. However, when it was announced that US astronauts would depart for the Moon aboard Apollo 11 on July 16, 1969, the Soviet Union decided to act.

Sending cosmonauts to the Moon was out of the question, but there was a way to sugar-coat the bitterness of losing. Luna-15 was intended to be the first vehicle to collect lunar soil and bring it back to Earth. This objective was classified, and the launch was deliberately slated for three days before the US mission.

To NASA, the Soviet mission seemed a very strange undertaking. It meant two objects at once would be transmitting radio signals from the Moon back to Earth. Moreover, nothing was known about the Luna-15 flight plan. The US space agency was afraid of unwanted interference, and even sent Apollo 8 commander Frank Borman to the Soviet Union. He was on good terms with the Soviets, and became the first US astronaut to visit the country. He was able to confirm that there would be no problems.

USSR astronaut German Stepanovich Titov (right) and American astronaut Frank Frederick Borman (center)

Alexander Mokletsov/SputnikTo begin with, it all went according to plan. The five-ton Soviet station (everything was bulky back then) approached the Moon on July 17, three days before the now airborne Apollo 11, and went into near-lunar orbit. But then, the unforeseen happened. For some reason, the spacecraft got stuck in lunar orbit, allowing Apollo 11 to sneak past. There are several versions as to why, ranging from on-board problems to the Moon’s gravitational field, which was still poorly understood. Meanwhile, Soviet physicists back on Earth were doing some desperate number-crunching to try to work out the best landing options.

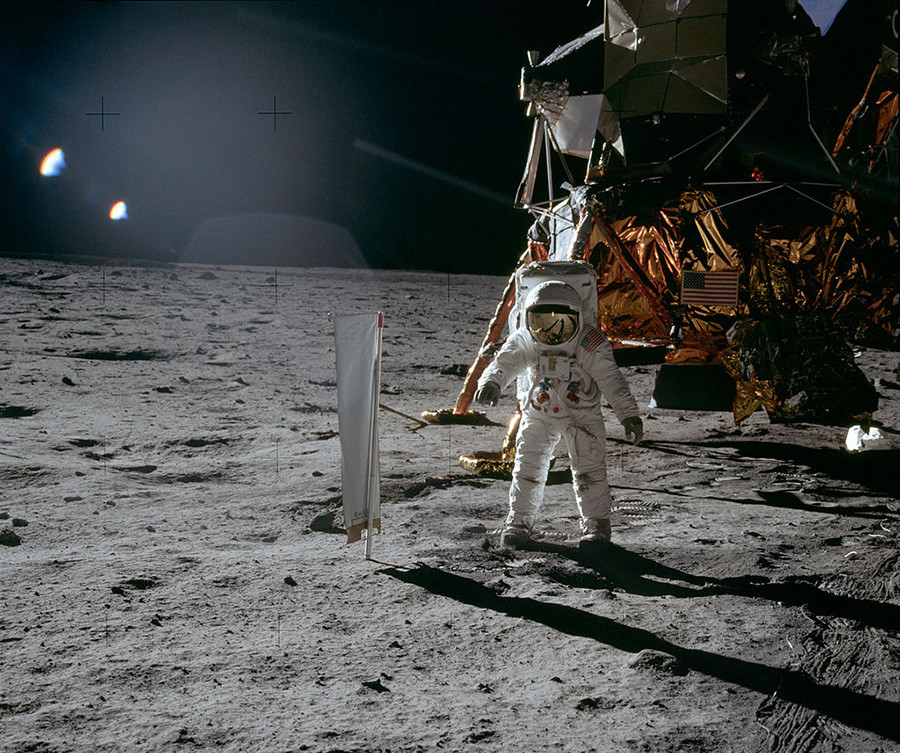

Apollo 11, Buzz Aldrin

NASAEven after the US team had landed, the Soviet controllers were still wrestling with the calculations. By the time Armstrong & Co. had taken their small step/giant leap and collected lunar soil in the process, Luna-15 had orbited overhead no fewer than 52 times. Two hours before Apollo 11’s lift-off from the lunar surface, the Soviet leadership decided it was now or never. And gave the order to land.

The unfolding drama was being watched back on Earth by British scientists at the Jodrell Bank Observatory. They were listening in on the voice traffic from both missions simultaneously with the aid of a radio telescope. In 2009, this audio recording was made public on the 40th anniversary of the Moon landing.

Suddenly, they realized that Luna-15 was not just there to take pictures of the lunar surface, but that the intention was to land. The scientists exclaimed “It’s landing!”, and continued to listen in. Their last, somewhat quaint words on the audio recording are: “I say, this has really been drama of the highest order.”

Four minutes later, Luna-15 landed – by crashing into a mountainside. The apparatus tumbled to the surface, where its remains presumably still lie. Space historian Asif Siddiqi, in his book Challenge to Apollo, would later write:

“There was one small irony to the whole mission. Even if there had not been a critical eighteen-hour delay in attempting a landing, and even if Luna 15 had landed, collected a soil sample, and safely returned to Earth, its small return capsule would have touched down on Soviet territory two hours and four minutes after the splashdown of Apollo 11. The race had, in fact, been over before it had begun.”

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox