The Bolsheviks turned the heavenly Solovetsky Monastery into a living hell. Wooden bunks for internees were built inside the churches; the altars and iconostases were smashed, precious wares were confiscated. And the former monastic cells and remote sketes for hermit monks were converted into barracks and insolators.

Modern-days Solovetsky monastery

Legion MediaToday, the monastery is functioning again, but has yet to be fully renovated. Many reminders of the camp remain. For example, the abandoned building beside the monastery housed the camp administration.

Construction of the White Sea-Baltic Canal

Gulag History MuseumPrisoners at the White Sea-Baltic forced labor camp had one task — to build the White Sea-Baltic Canal. At any one time, 60-100,000 people toiled on the construction site. The 227-km canal, stretching from the White Sea to Lake Onega with 19 locks along the way, was built in record time — less than over two years. During the construction about 12,000 workers died.

The White Sea-Baltic Canal in our times

Ilya Timin/SputnikToday, the White Sea Canal is still in operation, having been reconstructed several times. Along the canal are several monuments to the dead laborers. In addition, the White Sea-Baltic Canal historical-and-cultural complex was created and includes preserved buildings and memorials to the prisoners.

Norilsk camp

Gulag History MuseumThe Norilsk camp existed from 1935 to 1956, (in the early 1950s it held the record amount of prisoners - up to 72,000). The list of tasks was very wide-ranging. Inmates worked at the copper-nickel plant and down mines in conditions of extreme cold; they also built and maintained the railways, and unloaded barges. Modern-day Norilsk is essentially a city built by forced labor.

The Norilsk Golgotha memorial

Sergei Pyatakov/SputnikToday it is a large industrial center with a population of around 180,000 (read more about modern Norilsk here). In the 1990s, the Norilsk Golgotha memorial was installed at the site of a mass grave of camp prisoners. It is dedicated to the different nationalities of those who perished, including Russians, Poles, Lithuanians, Estonians, and Jews. The Museum of Norilsk museum-and-exhibition complex features a permanent Gulag exposition with personal belongings of prisoners and fragments of their memories.

The Perm-36 Museum of Political Repressions

Gerald Praschl(CC BY-SA 3.0)This camp settlement in Perm existed from 1946 to 1988. Its inmates were mainly engaged in logging. The majority of the prisoners were intellectuals, writers, and leaders of religious and human rights organizations, as well as dissidents prosecuted for anti-Soviet propaganda.

The Perm-36 Museum of Political Repressions

Max Kimmerling/TASSIn the 1990s, not long after its closure, the Perm-36 Museum of Political Repressions was opened on the site. Part of the exposition is located right inside the former prison barracks. This is one of the few places in Russia to offer a genuine glimpse into what prison life was actually like.

Vorkuta camp

Gulag History MuseumIn the 1930s, following the discovery of coal deposits in the region of modern Vorkuta, brigades of prisoners were sent to mine them. As a result, one of the largest and most notorious camps in the USSR took shape. Prisoners built railways and mines, and extracted coal in the utterly inhuman conditions of the Russian Far North.

The ghost town of Yur-Shor

Oleg-2014(CC0)In 1989, the Vorkuta museum-and-exhibition center became one of the first expositions about the history of the Gulag to appear in the Soviet Union. Today, there is also the “Vorkuta Circle of Mines” tourist trail, which traces the footsteps of prisoners at work and for which a mobile app with augmented reality was specially developed.

The city of Vorkuta itself, one of the largest in the Arctic Circle, was essentially built by Gulag labor. To this day, it remains a single-industry city, namely coal mining. Not far from Vorkuta lies the ghost town of Yur-Shor, the scene of one of the largest camp uprisings in Soviet history, plus a memorial cemetery for miners who perished at Vorkuta.

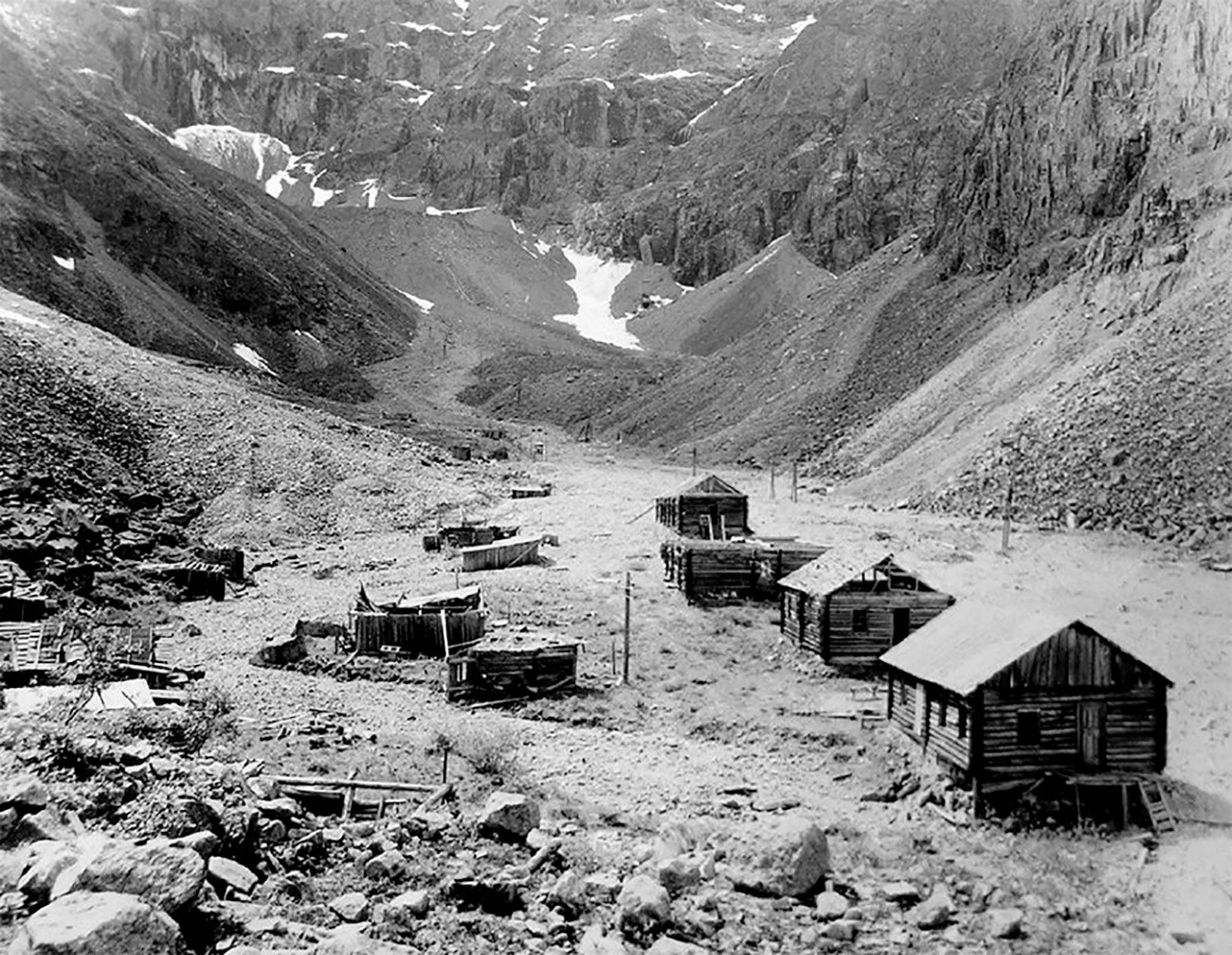

The Butugychag camp (which translates from the Even language as "valley of death") at Kolyma

Gulag History MuseumThe Kolyma region extends along the Kolyma River in the Russian Far East. It is known for its gold mines and the horrors described by Varlam Shalamov in his Kolyma Tales.

In addition, valuable ores were mined in Yakutia, Kamchatka, and the Magadan region, as well as radioactive uranium. Prisoners here worked practically bare-handed in the permafrost; they also constructed the city of Magadan.

The Dnieper camp and a mine in the Magadan region

Gulag History MuseumSeveral prison barracks and watchtowers lie abandoned throughout the territory of modern-day Kolyma, while Magadan is now a fishing and machine-building city.

Severny (North) uranium camp, 2015

Gulag History MuseumIt was on the back of forced labor that the Soviet Union opened up Chukotka and discovered there a rich vein of tin deposits. A metal-mining industry was established, around which towns, cities, and infrastructure were built.

In 2015, employees of the Gulag History Museum went on an expedition to Chukotka to explore what was left of the camps where prisoners had slaved to extract, among other things, radioactive uranium (without protective clothing, of course). Many of the former barracks lie abandoned. A terrifying sight...

Vostochny (East) uranium camp

Gulag History MuseumMore photos and videos from the expeditions are available on the museum website. The museum offers a 3D tour of these sites with VR glasses.

Houses where guards securing the prisoners of Bamlag used to live.

BAM History MuseumIn terms of prisoner numbers, the Bamlag camp was the largest in Soviet history; 1938 saw a record 200,000 internees.

Tasked with developing the Trans-Baikal territory in the Russian Far East, they were mainly engaged in the construction of the Baikal-Amur mainline railway (BAM). However, the project was mothballed during WWII, and only completed in the 1980s.

The Baikal-Amur Railway

TransmashholdingToday, the only reminder of the camps is the BAM itself, which is one of the longest railways in the world. In the city of Svobodny in the Amur region, local residents managed to have a memorial stone installed in honor of those who perished.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox